One of the most important features of JavaScript is functions and today I will cover the vital topics about it starting from the beginner’s level up to more advanced things.

Functions can be flexible, reusable, and modular but if you don’t know their key features, you might miss out on using functions at their fullest potential.

What is a function?

In simple words, functions are actions or processes that receive an input and return an output. They can perform various tasks and calculations.

For example, if I want to calculate something when the user clicks the button, I will write a function for that action.

If I want to close the image modal, I will write a function.

If I want to remove something from a shopping cart, I will write a function to achieve that.

I can even write one function that can run another function. I can control functions with other functions.

How to define a function?

To start using functions, you need to define (create) them. You can define functions in various ways.

Common ways to define a function:

Function declaration

Function expression

IIFE (Immediately invoked function expression)

Arrow function expression

Function constructor

Generator function

Methods

We are going to go through each of these topics in more detail and expand on a lot of interesting features of JavaScript functions.

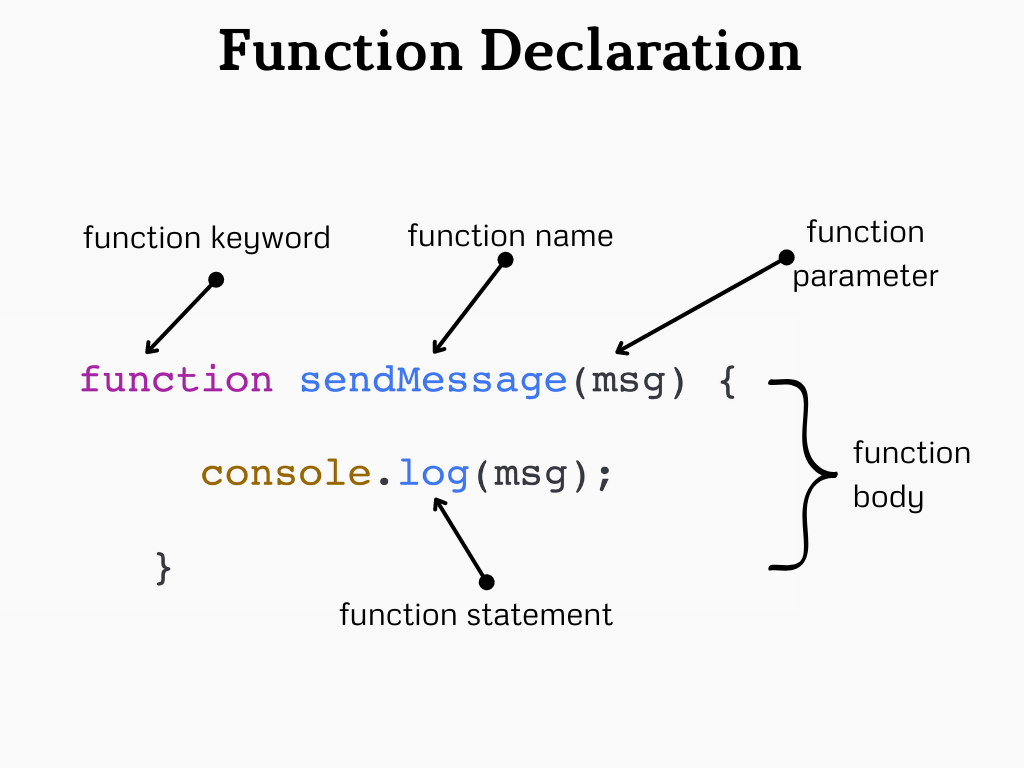

Function declaration

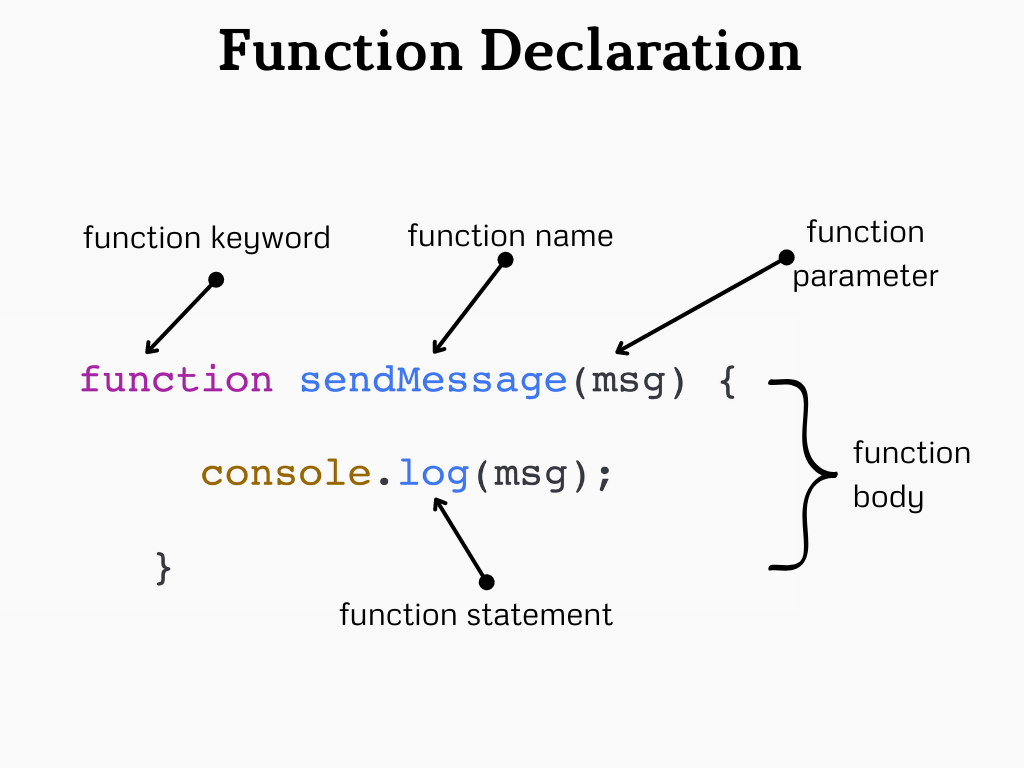

One of the ways to define a function is a function declaration. When you create a function with a name, it’s called a function declaration (aka function definition or function statement). This is the most standard, basic way of writing a function and what you will use very often as a beginner.

Here is an illustration of a function declaration:

The function declaration above consists of:

A function keyword

The name of this function

A parenthesis that holds the parameter(s)

The body of the function, enclosed in curly braces with statements that define the function

The function named sendMessage receives a parameter of a message and then logs this message to the console. When will this function or how will this function do it? We will cover this very soon.

Function keyword: To create and use functions you always need to use the keyword function as it’s a part of JavaScript syntax that helps JavaScript to identify what you are trying to create.

Function name: A function name is a way to identify the function. When you have various functions you need to differentiate which one does what for later use.

Function parameter: It’s the name of a potential value that we can pass to the function. Imagine, you have a function that console logs a name every time you click a button. I can pass inside the function the parameter that will have a value later. This function will receive this value and then log it to the console. Function parameters are not mandatory.

Function body: This refers to the block of code inside curly braces ({}). This is a place where we can provide function instructions.

Function statement: Inside the body, we can have function statements and expressions that are the tasks or processes we expect the function to perform.

How to call a function?

Once you create a function you also need to call it. When you call the function, it performs the tasks you write in the function body. There are functions that don’t need to be called.

Functions can be also called differently but it’s a special function that we will cover later.

The basic that you need to understand right now is that to call a function you use its name followed by parenthesis. Just like with people. To call someone you use their name, so in the case of functions, it’s the same.

As an illustration, here is a function hello:

This function is not going to show us anything in the console right now because we didn’t call it.

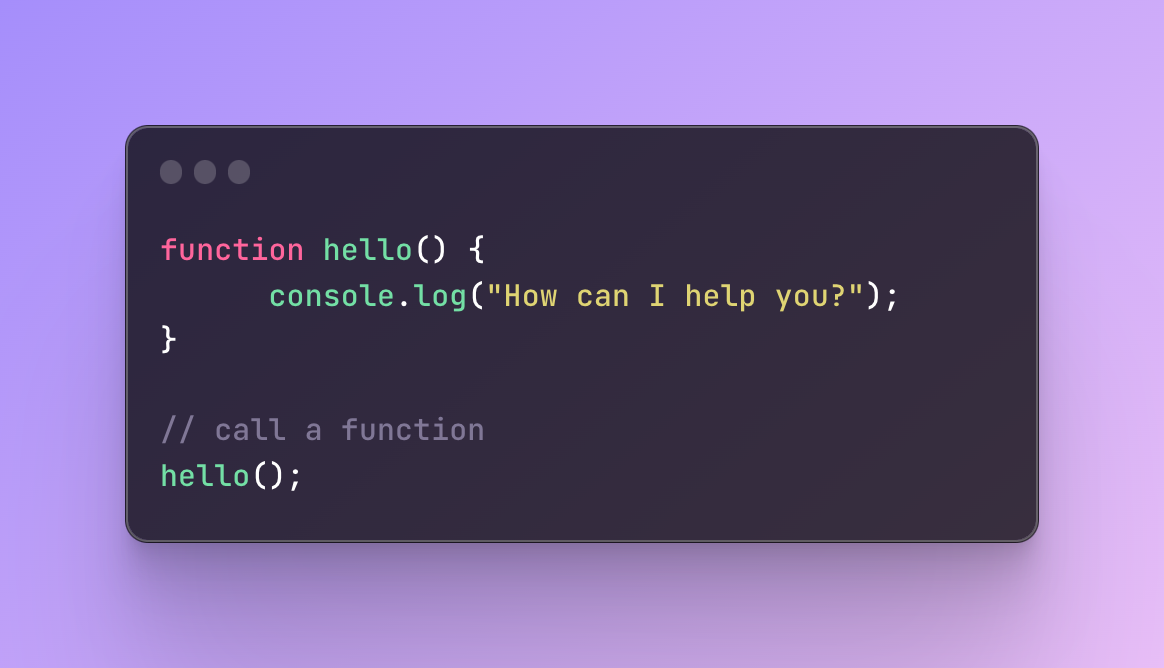

That’s why we need to add one more line:

And only now we will see “How can I help you?” in the console.

What is a function parameter?

A function parameter is a name that we include when creating a function. This name will potentially be a value that the function receives and later performs some operations on/with it.

The name that you come up with can be any, it’s up to you what the name will be and doesn’t affect the result. The parameter names are needed to associate them with future values we plan to pass to the function.

There are several rules to remember when it comes to parameters:

The names cannot be repetitive. If you use one name, the next one needs to be different.

You don’t always have to use parameters. They are not required.

The order matters. If you want to pass parameters of a name and surname, the values you plan to pass, need to match the order. If your second parameter is called last name but you pass a name as a second value, the value of the last name parameter will be the name value.

You don’t define the data type of the possible value. JavaScript is a dynamically typed language meaning that you don’t have to write in advance what data type the parameter is going to be.

If you have not already make sure to read about data types in JavaScript.

- Parameter names need to be descriptive and it’s recommended to use camelCase (lastName, firstName) but not a must.

The must-know along with parameters are arguments.

What is a function argument?

A function argument is a value that we pass to the function. The value will be represented by the function parameter. When I use parameters like name and last name, the values that I will pass, will be called arguments.

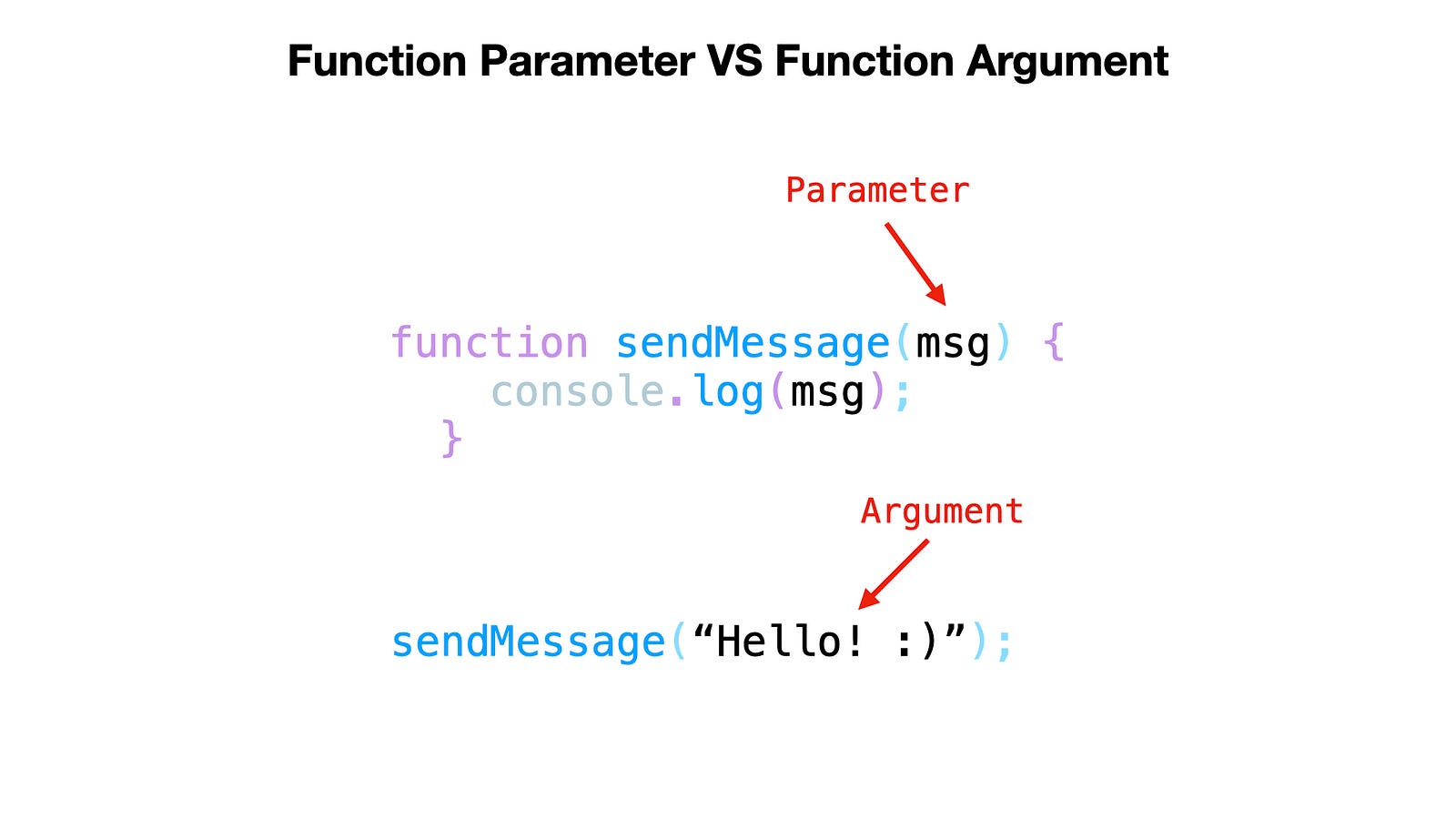

Here is some visualization:

According to the image above, the name msg is the parameter but the actual value, “Hello! :)” is an argument.

Arguments object

An argument object is a built-in object available inside the body of the function. It represents all the arguments that we passed into the function. This object is more similar to an array but it’s not a regular array we know of.

If you have 4 parameters in the function, for example, but you pass 5 arguments (values), the arguments object will read all the arguments you have passed, even if there is no parameter to read it.

You can use an argument object and combine it with array index functionality.

An index is the location in the array. The index of the very first item in an array is 0, so its position (index) is 0. The next one is at the index 1 and so on.

Here is an example:

In this function, I used only one parameter but passed two arguments. With the help of the arguments object I targeted the argument at position 0, then at position 1 (the second one). Finally, I targeted the argument with the parameter name.

The arguments object can be a powerful tool but considering that it lacks some functionalities, in the modern world you can simply replace the arguments object with the rest parameter.

The rest parameter

Instead of using the arguments object, we can also use a rest parameter which treats one parameter as an array of several arguments.

For example, if I wrote one parameter name but passed several arguments, I can actually retrieve all these arguments by “spreading” my parameter. To “spread” the parameter name, you can use the three dots (…) before the parameter name. The name can be anything you wish as it is something created by you, all the other previous rules don’t change.

Here is an example based on the previous function:

In this function, instead of writing one parameter name, I added three dots. These three dots will retrieve all the existing arguments and combine them into an array.

Here is another example if I pass one argument:

The result remains similar.

Let’s see what happens if I don’t pass any arguments:

It will return an empty array because there is nothing to save in the array. As a result, this is a better way to access all arguments compared to the arguments object as we can manipulate it as a regular array.

Default parameter value

Sometimes there can be a situation when your function has two parameters but doesn’t always receive two arguments.

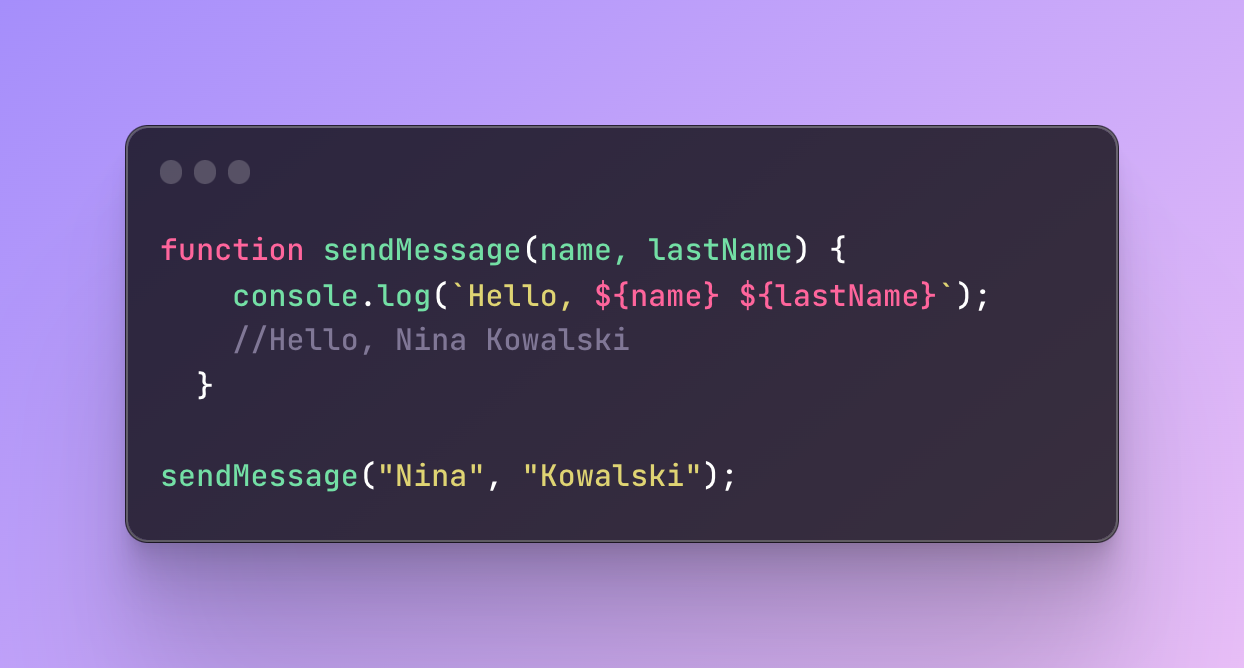

First, let’s remember what happens when we pass both:

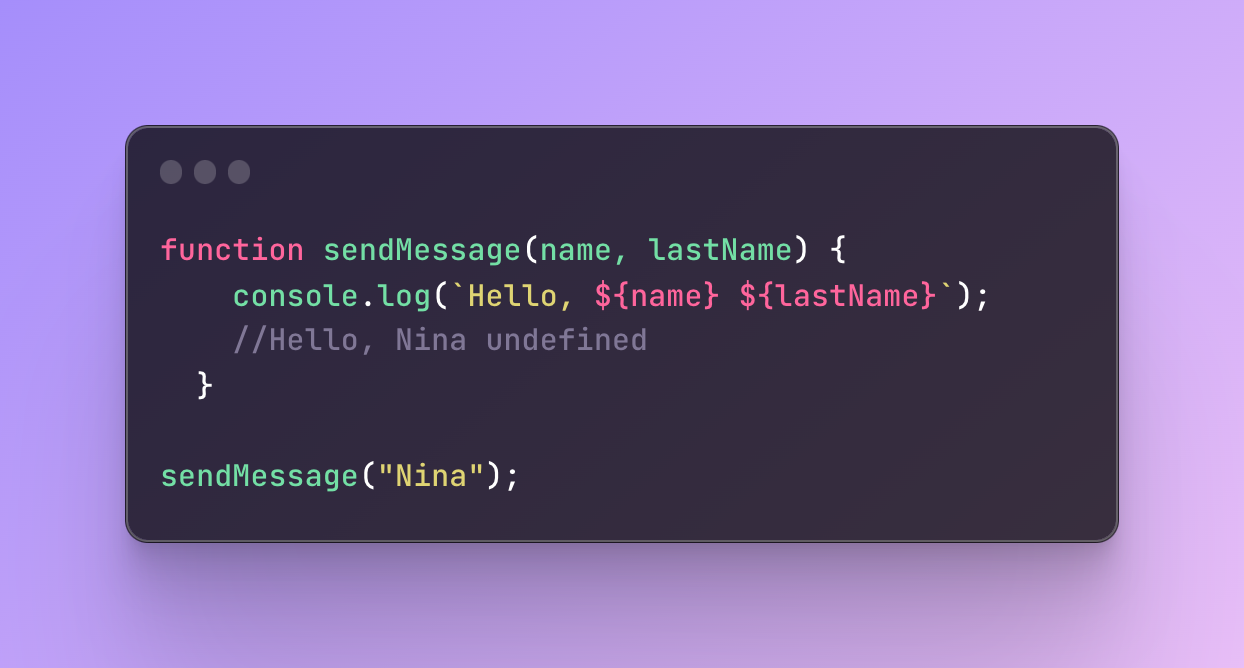

Next, let’s see what happens if we don’t:

Instead of the last name, we see undefined because the parameter wasn’t given any value.

When you have a real website and users, it might be not very good if the user of your website saw something like this, right?

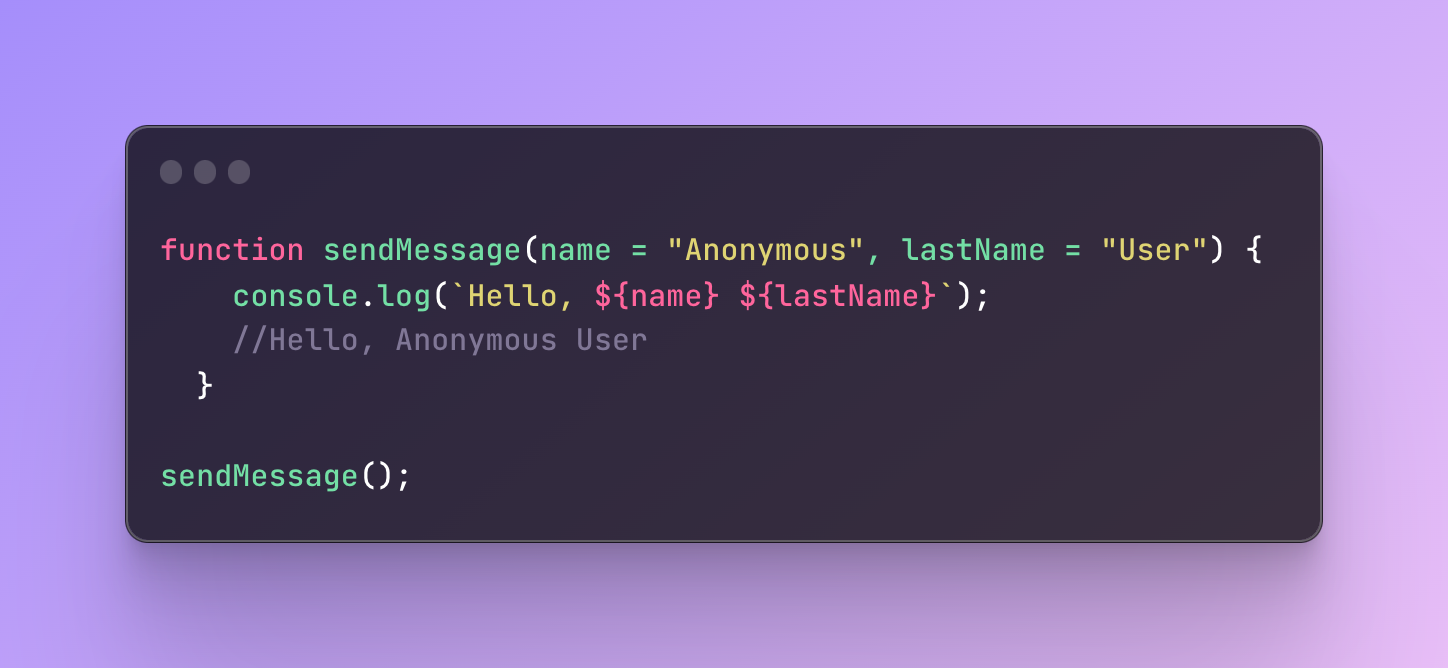

How to solve this? We use a default value!

As the name suggests, the default value is a value we can assign to the parameter that will be a default. If we don’t pass anything the starting value will be this default value.

What value can we give? Any value you like!

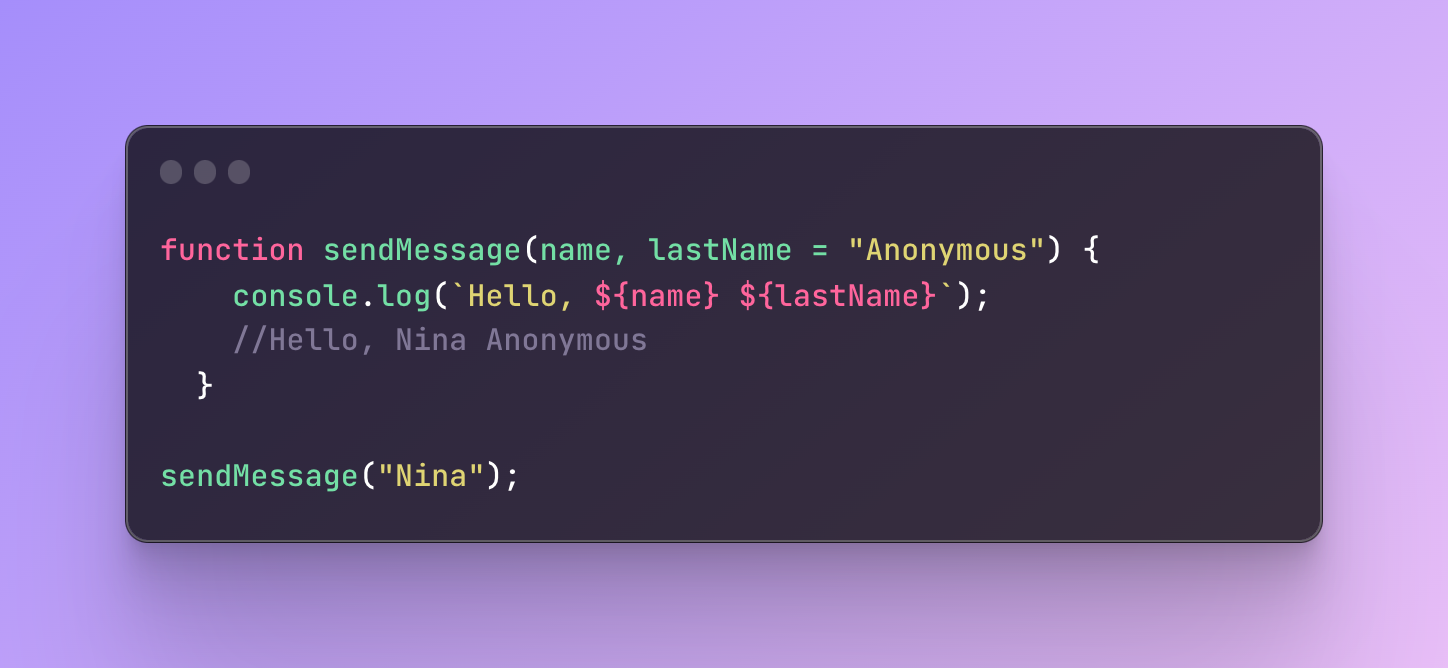

In this case, we can add a default value “Anonymous” which will be used in case we don’t have a last name:

If the function doesn’t receive the last name value, the default value Anonymous will be used.

On the other hand, there are other ways around this.

You can check if the last name is undefined and show different results conditionally but I think the default value is more convenient.

A default value can be any parameter at any position and even several of them.

Return statement in functions

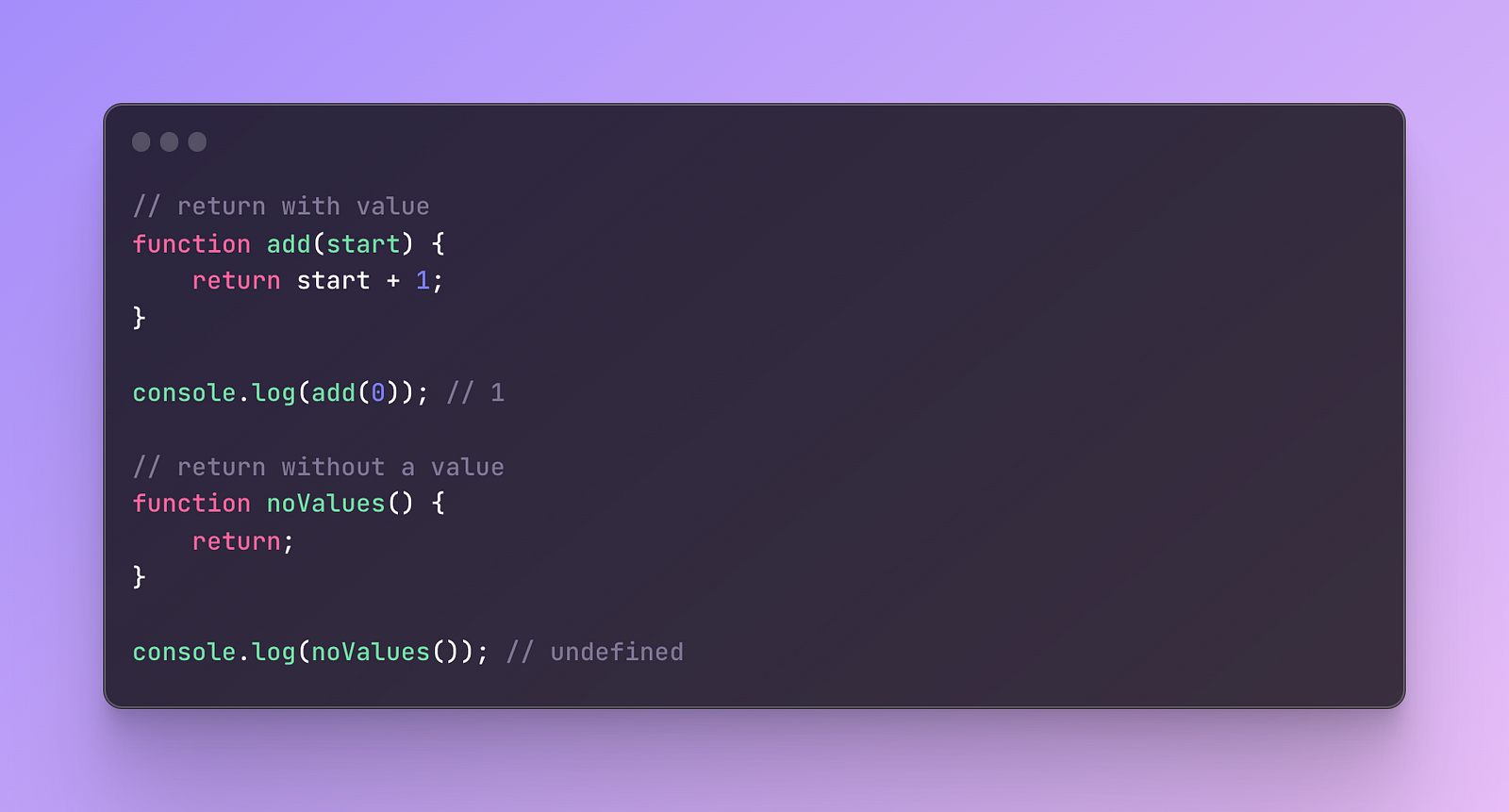

In a function body, we often use a return statement. A return statement returns one specific value and stops the function execution. Any code you have after the return statement is not going to execute. That’s why the return statement should always be the last one.

The value returned can be any data type. It’s also not mandatory to write a value after the return statement. If you skip the value, the function will return undefined.

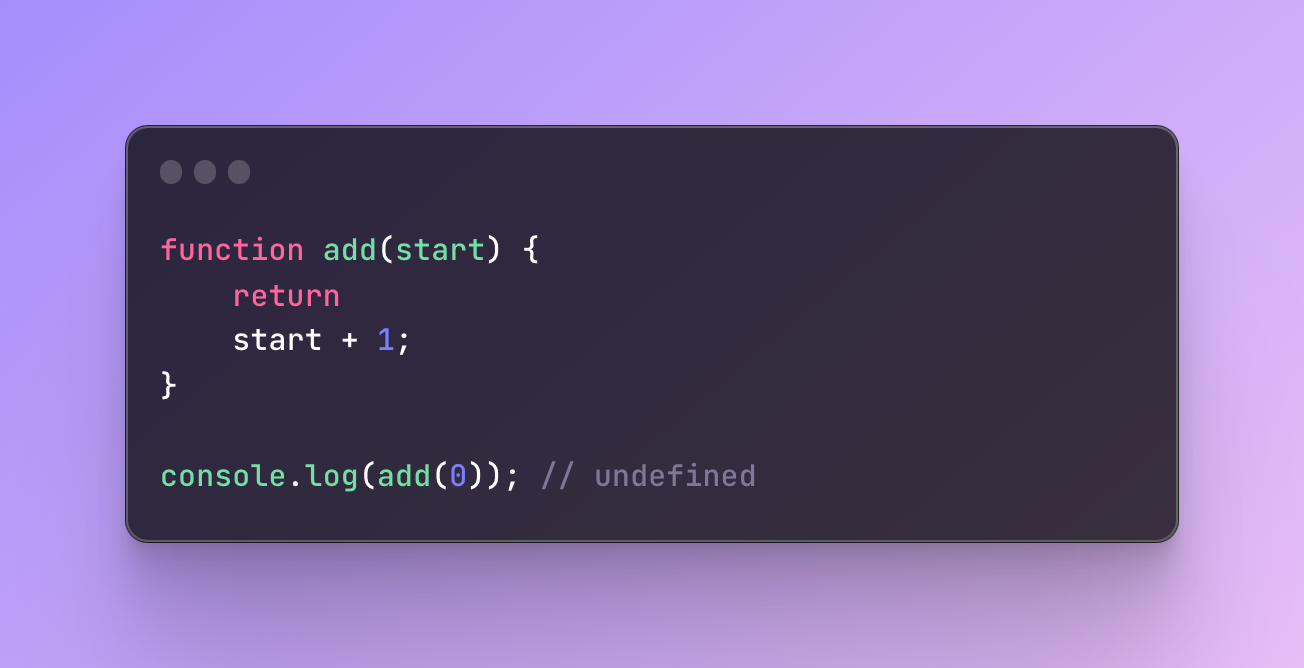

The value you want to return always needs to start from the same line where the return statement is located. If done otherwise, this line break will be automatically considered as a semicolon. JavaScript automatically inserts a semicolon after the return statement even if you don’t do it yourself and this new line will be closed.

To avoid this issue but use a new line anyway you can simply wrap a parenthesis around the value you want to return:

Now it should be working properly again.

What does the return statement do:

In regular functions, the return says “ I am done, here is the answer”, stops doing anything and gives you the value you asked for from the place where you called the function.

In the asynchronous function, it says “I promise to answer you later when I am done” and remembers that it will answer later.

In generator functions it says “I will give you right now this part of the answer but I might have more as well”.

In the asynchronous generator, it says “I promise to give you some part of the answer later but I might also have some more answers but I also promise I might give them later on”.

If you don’t understand some terminologies, don’t worry, we will cover it very soon.

Before we continue further, let’s remember the function declaration structure one more time and move to a function expression:

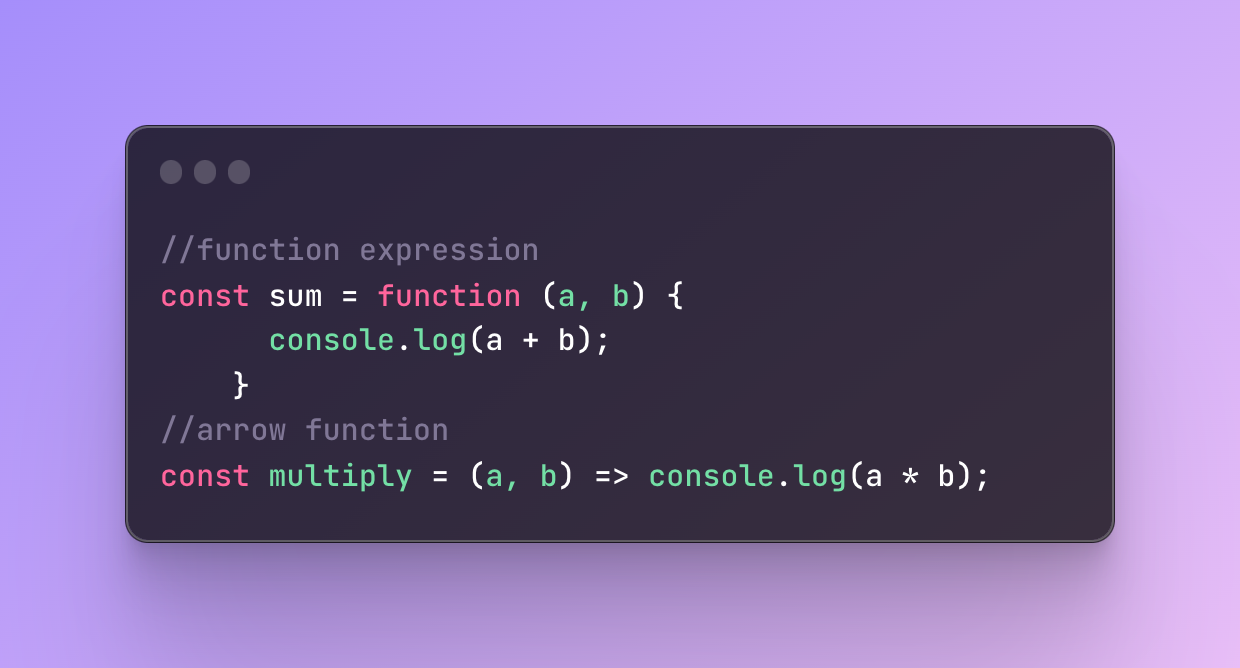

Function expression

Another way to define a function is a function expression.

In function expressions, you have two options:

You can create a function expression without a name (aka anonymous function) or

You can create a named function expression

The main difference is that in function expressions you can have an additional perk of not naming the function. In a function declaration, you always name the function.

Anonymous functions (unnamed function expression) vs. named function expressions

As the name suggests, the anonymous function is a function that doesn’t have a name, here is an example:

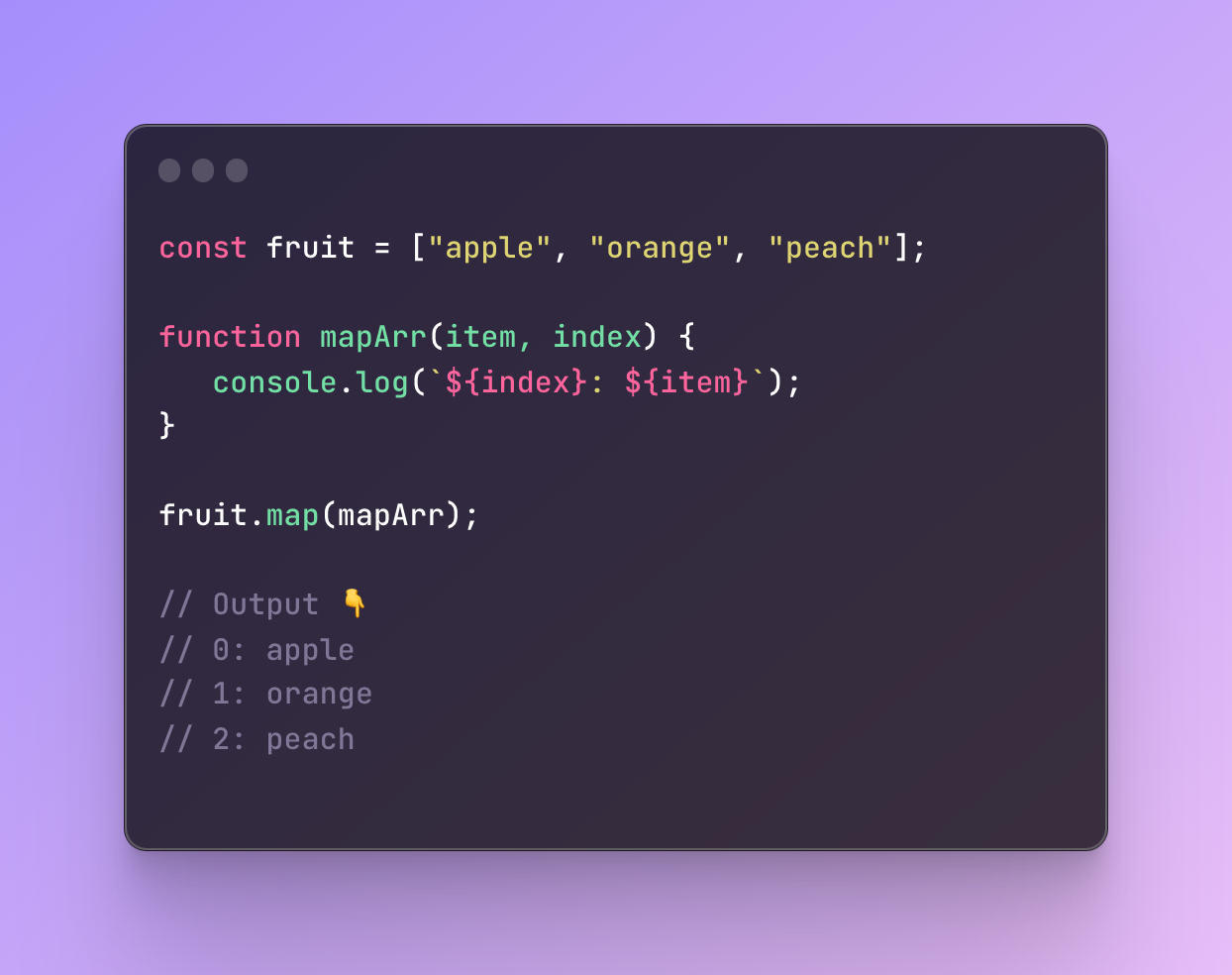

I am mapping through the array of fruit and I use a function without a name. This function is a function (specifically a callback function) that runs for every element in the array.

At the same time, you can optionally use a name for this function. BUT in this case, it will be a named function expression, not an anonymous function. As anonymous means that it doesn’t have a name, it’s anonymous.

Let’s try this out:

As you see, the result is the same. In this situation, we would not need to use any name because this function runs only once and we don’t use it outside of the code block.

We can take the function declaration we created earlier and transform it into an anonymous function:

In this example, I created the exact same function however it does not have a name anymore. I omitted the name which was supposed to be written after the function keyword but there is nothing right now.

However, a function written in such a way is going to throw an error:

🚨 Function statements require a function name

This code will be treated as a function statement and that’s why it requires a name.

Function expression vs. function statement

A function statement and a function expression are slightly different things in JavaScript.

A function expression means that we are able to create functions in the middle of expressions, so that’s why it’s called a function expression.

What exactly is a function expression?

Expression in JavaScipt is a block of code where you ask a question in a way that gives you a specific value.

Let’s say you make a calculation and you want to check how much is 1 plus 1. The value given back will be a summary of 1 and 1. And this 1 plus 1 is an expression. Expressions usually produce specific values. While statements, that are very similar produce specific actions. For example, declaring a variable, or doing something with an if statement. So you are making a kind of statement.

In JavaScript, you can use expressions when a statement is expected but you cannot use a statement when an expression is expected.

For the function to be a function expression you cannot start it with a keyword function and not use a name if you aren’t calling it. In such a case, you need to save it somewhere. The keyword function can be treated differently depending and where and how it’s used.

For the keyword function to begin an expression (something that produces a value), it needs to be used in a context( a place in a code) where JavaScript doesn’t expect some statements (commands, actions). Otherwise, the keyword function will start a statement and we need to somehow indicate that I want an expression.

To avoid this error and make a function expression usable, we need to:

Save a function expression in a variable

Or use a function as an IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression)

Saving a function expression in a variable

Let’s fix the error above by saving it in a variable:

In this example, we saved the function in a variable and left it without a name. On the other hand, if I try to check the name of this function right now, it will tell me that the name of the function is sendMessage even though I did not name it.

Why?

This type of behavior is called name inference which helps to find the function with the help of the variables where we saved it. So what I did is that I saved an anonymous function ( a function without a name in a variable) and JavaScript gave a name to it anyway, specifically the variable name where I saved it.

Practical reasons to save unnamed functions in a variable (besides the technical reasons)

When we write regular functions, function declarations that have a name, we can use their names to invoke (call) them.

For the function to work and give you a result you need to call it by its name. The naming of the function helps you to identify it, that’s why the name is also called an identifier in programming. Just like with people, when they are called by their name, they know that it’s them being called. Imagine you wrote 10 various functions that do absolutely different things. How would you make that one specific function do something if doesn’t have a name? If we decided not to name a function expression and omit the name, we would have to save it in a variable so we can refer to it later on.

On the other hand, if you are 100% sure you will never need to re-use the function then you have other options to skip the name. It doesn’t mean functions always need a name.

As many say, “names are a good thing” so let’s try to understand more benefits of named functions.

- Readability: When naming a function, if done appropriately, it helps to make a code more readable as names are usually kind of a short explanation of what the function does. When you work on a project where there are a lot of functions and there are different people working on it, it makes it much easier to understand faster and more clearly what the function does.

On the other hand, one can add additional comments or documentation to understand what is going on so maybe it’s all about the preference.

- Tracing errors: when a function doesn’t work properly and it throws an error, without a name it would be so much harder to understand where exactly or why there is an error.

When you see errors, you trace the reasons for the error with the help of a name. That’s why names make debugging much easier. There are other ways to make debugging like name inference — finding an unnamed function with the help of the variable where we saved it.

- Recursion: recursion, which we will cover in more detail very soon is a technique when a function can call itself. It executes code and then calls itself again which can be stopped if it meets specific conditions. And to make a function call itself it needs to have a name, an identifier.

To finalize, if you have a function you want to use later without a name it’s more complicated. There are some disadvantages for sure but this doesn’t mean that anonymous functions are useless.

When to use anonymous functions?

There are several cases when you can use anonymous functions without having the need to name them and save them anywhere. Defining functions without a name reduces your code and time as long as you use them correctly.

Situations when you can use anonymous functions are:

Higher-order functions (HOF)

Closures

Higher-order functions (HOF)

Higher-order functions are functions that as arguments can receive a function and manipulate it, or even return a function as a result.

Functions in JavaScript are treated on a similar level as data types like numbers or strings.

Functions are treated as values and this is what makes them more powerful.

The behavior of functions being able to be a value makes functions be called “first-class citizens” or “first-class functions”.

A function is a first-class function if it is a first-class citizen. Rarely but sometimes it is also mentioned as a first-order function.

What makes functions a value?

You can assign functions to variables and reuse them

We already covered this topic when it came to anonymous functions. Functions can be saved in variables and re-used as many times as you want.

Pass them as arguments

You can create a function that receives another function and performs additional. Such functions are known as callback functions which I will cover later in this post.

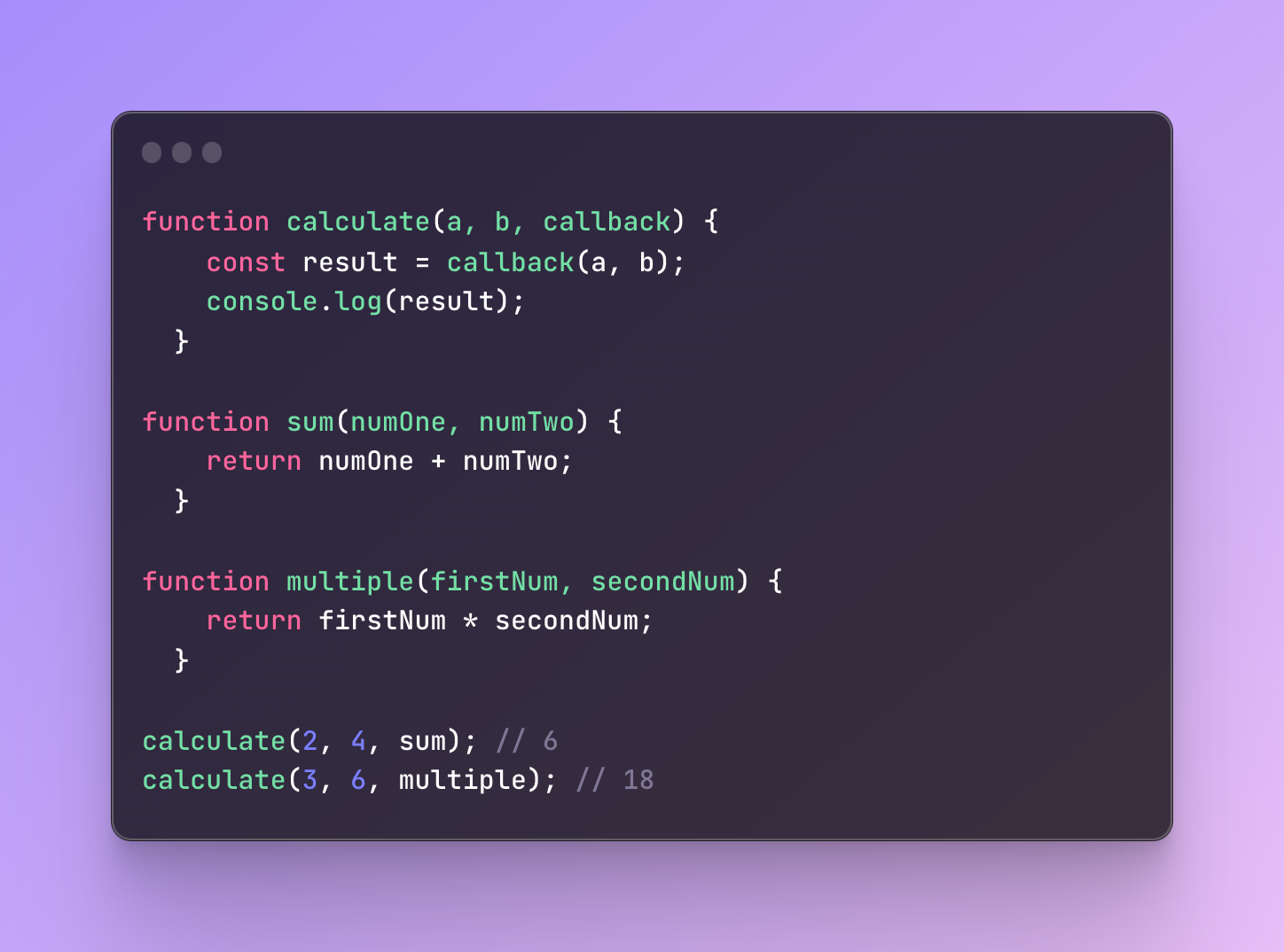

In the example above, I have a function called calculate that has three parameters. The third parameter is a callback which will be a function.

I have two various functions that I can potentially pass as an argument (value). It can be either a sum function or a multiple function. These functions on their own don’t do anything until I pass them.

Inside the calculate function I create a variable named result and there I will be saved the result of the callback function.

The callback is just a name but when I pass, let’s say the function named sum, it will be used as a value.

The sum function will receive a and b from the calculate function and return me the sum.

The same applies to another function, multiple.

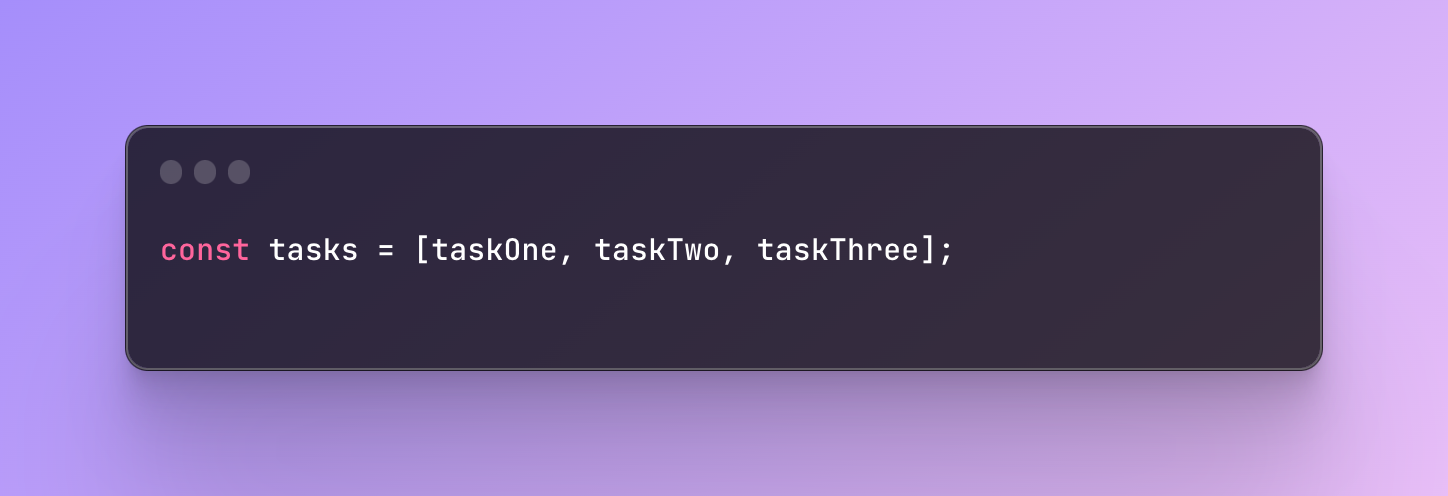

Store them in data structures like arrays

You can also store functions in an array for later use because they will be treated like regular values. One of the use cases can be a situation when functions are used as scheduled tasks and you need to perform some calculations one after another.

Return functions from functions

Function can not only use other functions but they can also return functions. This usually takes place when it comes to closures or factory functions which we will cover shortly.

Here is a simple example:

#1 First I create a reusable function that receives a message and returns a new function that will log the message along with its argument.

#2 Next, I save the result of the createMessage function in the variables receivedMessage. If you log this variable to the console, it will be a reference to the function. Try it out yourself!

#3 Next, I call this variable as if it’s a function, because it has a function value and I pass an argument “Nina”.

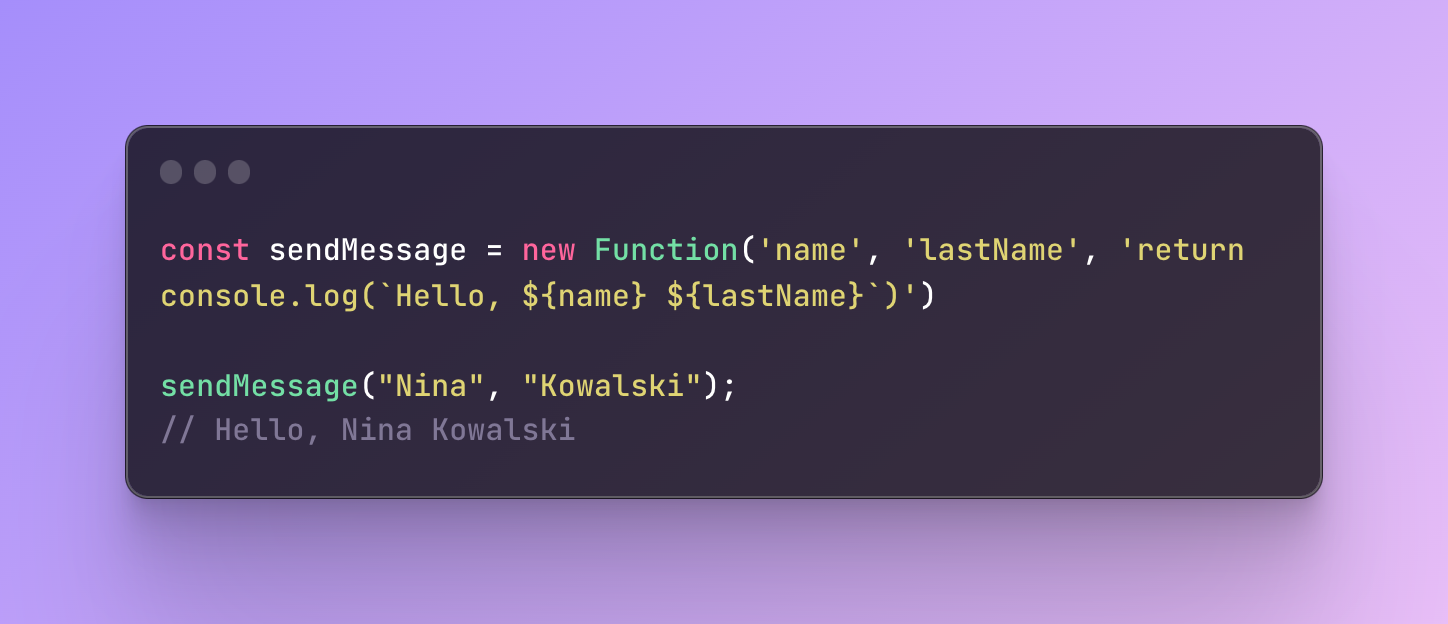

Create them dynamically

Finally, you can also create a function dynamically because they are just as dynamic as other values. To create a function dynamically you can use a Function constructor. A function constructor is a built-in object in JavaScript that can create a function from a code represented as a string.

To create a function with a function constructor:

Save it in the variable

Use the keyword “new” along with the Function constructor

Pass in any number of parameters

At the very end write the body of the function

Everything should be written in a string.

As powerful as it may seem, this is not the best practice and you need to use a function keyword to create functions. Currently, it’s not the best way to create functions.

More examples of higher-order functions

In JavaScript, we have many built-in functions(methods that I will explain very soon) that are higher-order functions. All these functions use other functions as an argument.

Higher-order function examples are:

map()

filter()

sort()

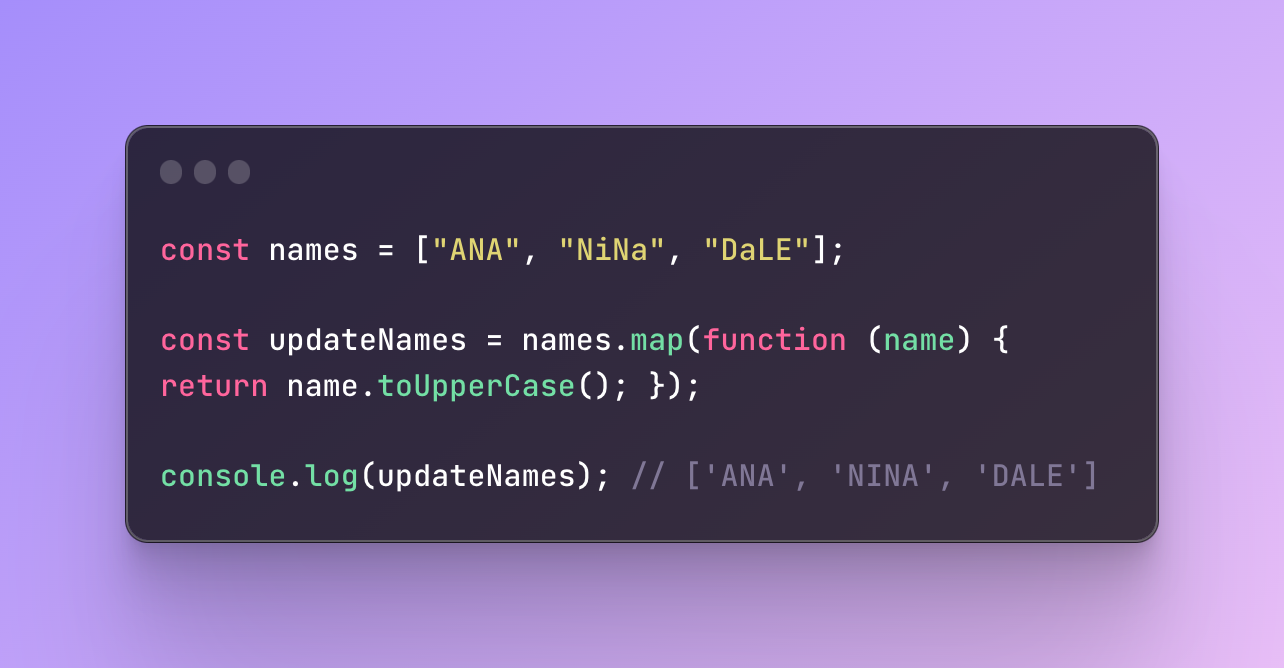

map()

The map is used to transform each element in the array one by one and perform a callback function on each of them. As a result, it returns a new array with new elements and doesn’t affect the old array.

As you can see, I mapped through each element and performed an action on each of them.

Considering that I am using an anonymous function, I can also omit the keyword function. But we will do this a little later when we reach arrow functions.

filter()

The filter does something similar to the map. It will perform a check on each element and return only the elements that pass this check.

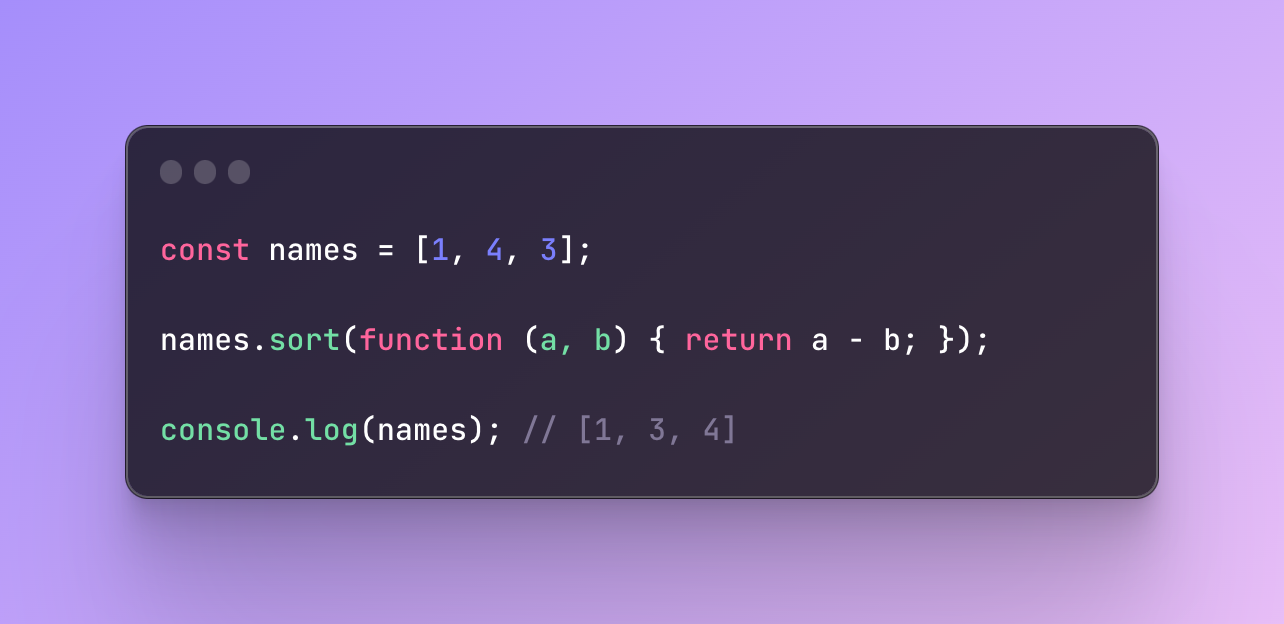

sort()

The sort, as the name suggests, is used to sort items in an array. It can be used in various ways depending on whether you want to sort in descending or ascending order.

In this example, we are sorting an array of numbers in ascending order.

These are several examples of higher-order functions that perform a callback function every time each element is called.

As you see, each callback function I used was an anonymous function. There are many other similar examples, like reduce(), forEach(), every(), and so on.

I mentioned callbacks many times and the functions above depend on callback functions. But before I expand callbacks, let’s cover closures real quick that will help us to understand the callbacks even better.

If you got lost, let me remind you why we started discussing this topic.

Situations when you can use anonymous functions are:

Higher-order functions (HOF)

Closures

Closures

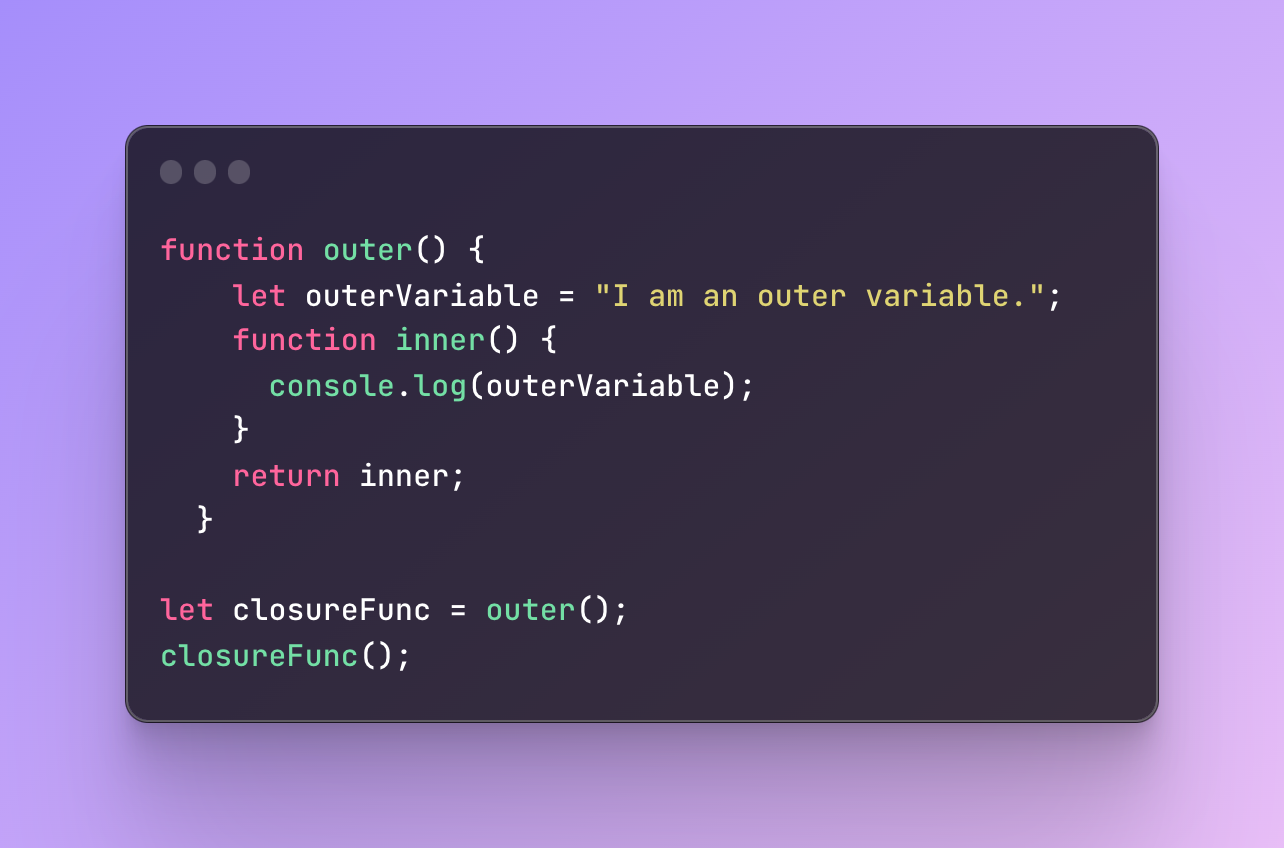

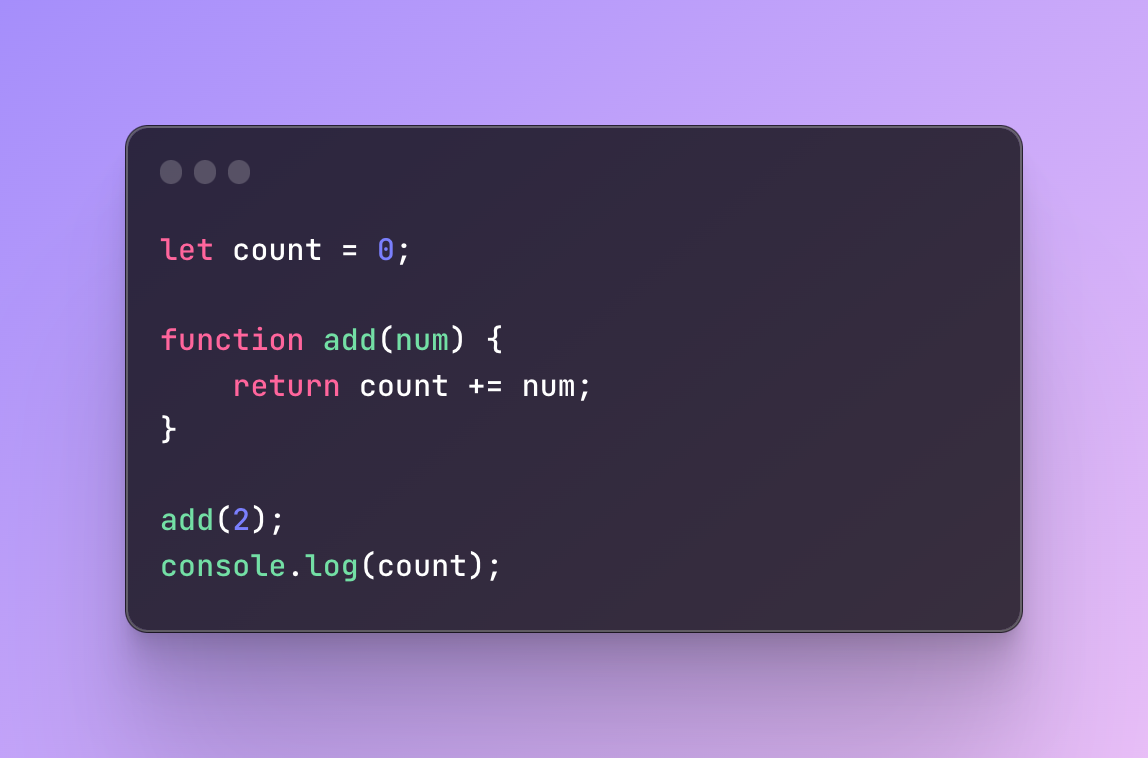

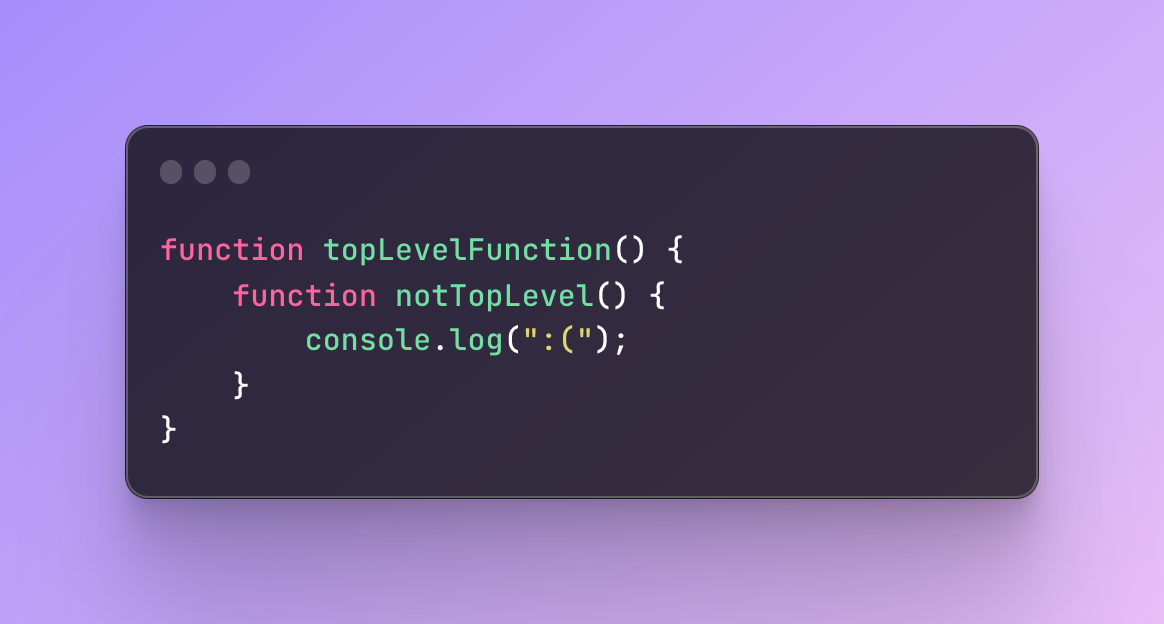

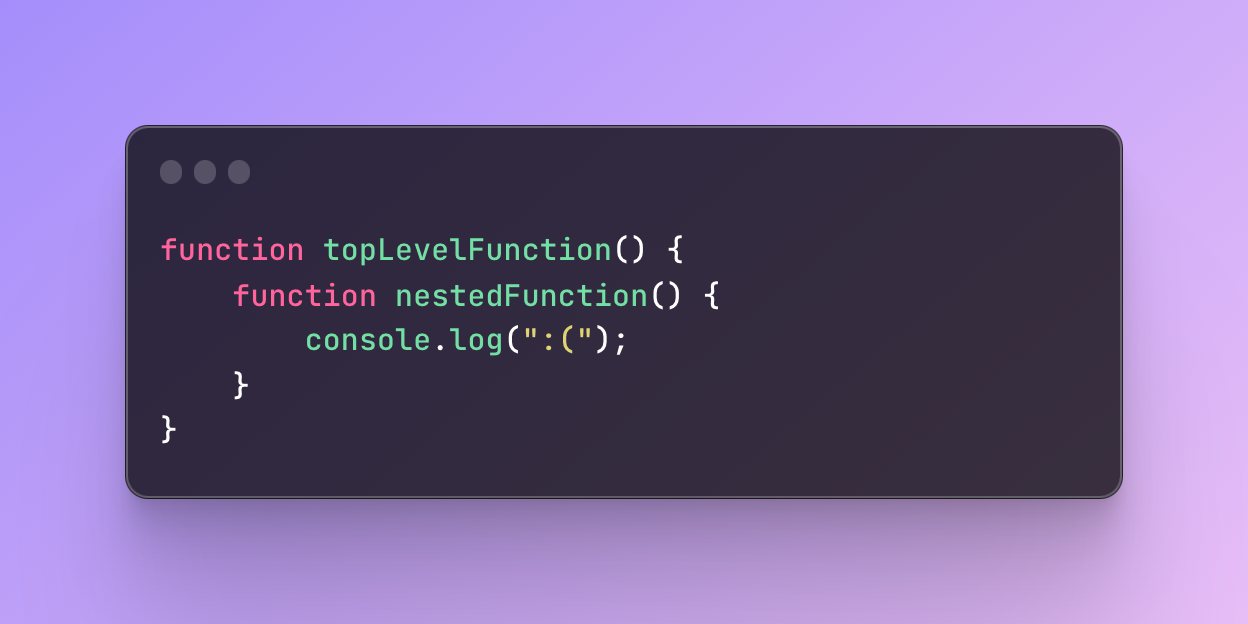

Whenever we create a function inside another function, the inner function receives access to the scope of an outer function.

An ability to access and remember the variables of the outer function is called closure.

If you are not familiar with the scope in JavaScript, make sure to read my posts about execution context and variable declarations in JavaScript to understand closures much better.

In the function messaging, I created a variable name. The name variable will belong to the scope of messaging (it’s available only inside the body of it). Then, I create another function called sendMessage which has its own local scope.

However, I am able to access the name variable anyway from the parent function messaging.

This is called a lexical scope.

This is the ability of the nested function to access the scope of its parent scope. But parent functions won’t have access to the scope of the functions nested inside of them.

Lexical scope refers to the context (the place in the code) in which a variable or function was declared.

Lexical scope and closure might seem very similar and even the same.

The closure doesn’t just have access to outer scope but it’s an ability to preserve it. It can access this variable even if the outer function finished execution.

The lexical scope defines when the variable will be available but the closure is the ability to retain access from the outer scope even when the outer function finished execution. In other words, the inner function encloses and captures the variables from the outer function.

What do you mean by the outer function finished execution?

The reason the outer function finishes execution first is how JavaScript works.

I definitely recommend you read my post about execution context because it will answer your questions.

Let’s try to understand why the outer function can finish execution earlier than the inner one.

Take a look at this example:

#1 For the browser engine to read javaScript it creates an environment called execution context where JavaScript code can be translated and executed in the machine code.

#2 We have two types of execution contexts — global execution context and function execution context.

The difference is that function execution context is created every time there is a new function and global is global for all variables outside functions and is created only once.

#3 When the code is being read, the first things that the engine wants to find are variables like const, let, and var. But it will target the variables located outside the function first (available globally).

If you keep reading the code line by line, you will see that the first variable found is closureFunc. When it’s found, it’s saved in the global execution context but it’s the name saved, the value doesn’t matter yet. It’s saved somewhere in the memory for later use. This name will be used to refer to its value later.

#4 When there is nothing to save in the memory, the engine will go back to the start. What is noticed next is the function declaration. Function declaration will also be saved as if it’s a variable and will be created in another separate function execution context. Remember why functions are first-class citizens? If not then I recommend you to go back and re-read about HOF.

#5 All the execution contexts pile up on top of each other.

The first is the global execution context, next, we have a function execution context on top of it.

#6 Everything there was to be saved, is waiting in the memory now and comes the phase of execution.

During the execution phase, the values are assigned.

Next, according to our code, we are trying to call the outer function and save the result inside the variable closureFunc. It’s the only variable we created.

This means we are at the phase where the values need to be assigned now. The value we saved in closureFunc is calling the outer function.

So once the value is assigned, JavaScript will know what to do next.

#7 The outer function will execute for the first time and this is where it’s going to finish execution.

Don’t look at the last line of code yet the closureFunc(). You need to look at the line when we assign the outer function. This is where the outer function is called for the first time.

Inside the outer function, we declared a variable innerVariable, and created a function inner. In other words, we didn’t call the inner function, we returned the inner function.

This means that we didn’t call the inner function yet and the outer one already finished the execution, it returned the inner function.

#8 When the outer function returns the inner function, this inner function is saved inside the global execution context variable — closureFunc.

#9 Finally we called the closureFunc that holds the inner function we never called.

Now when we call the closureFunc, the inner function will be called and this will lead to the creation of another function execution context that is pushed to the call stack.

As a result, it will log to the console the outer function variable, and its function execution context will be popped from the call stack.

Here is where closure comes into play.

If you were following, the outer function already finished execution earlier but the inner function that we called later, has access to the variable that was created outside of it.

I hope it makes a little more sense now.

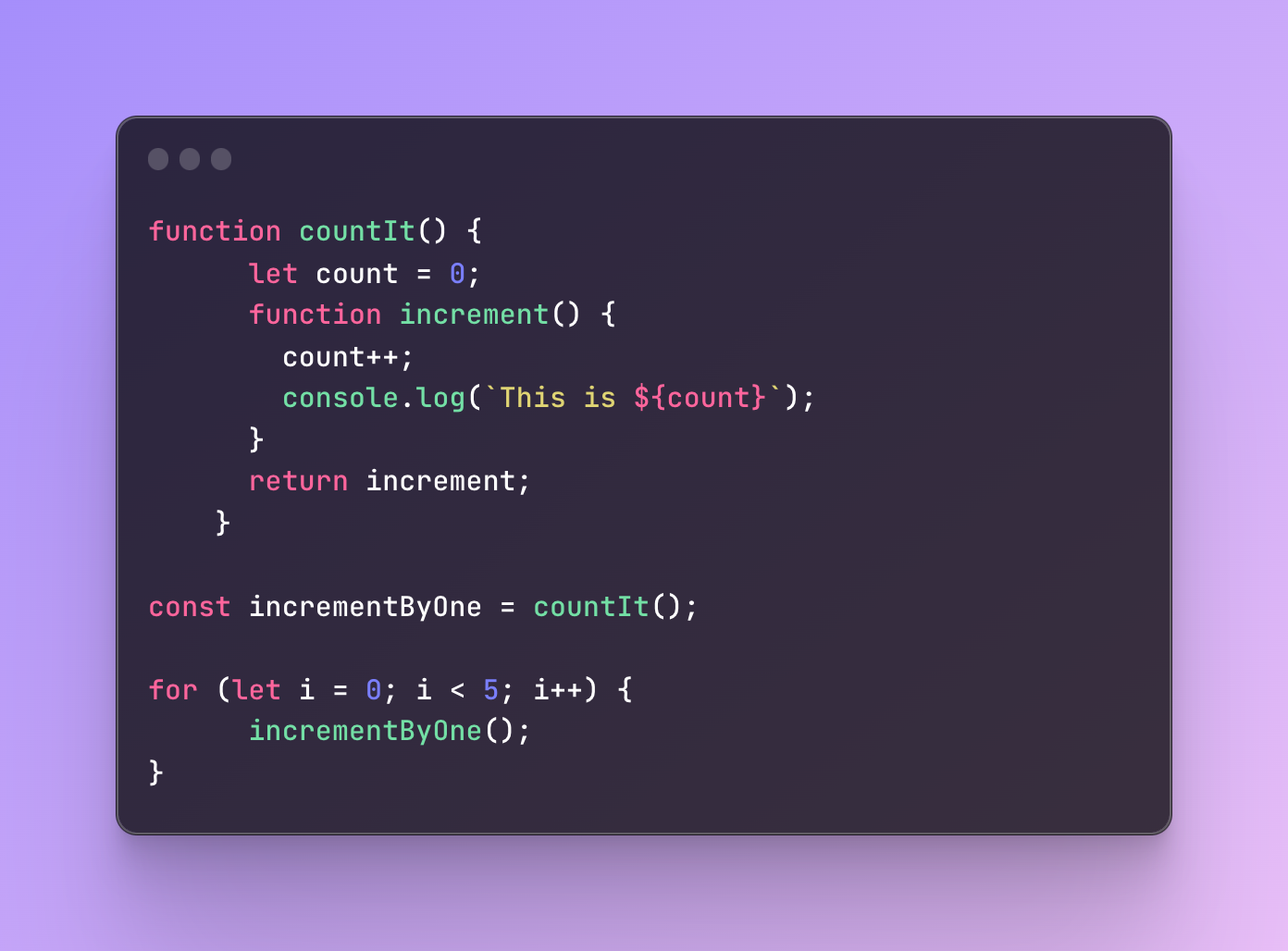

Closures in loops

Another example to understand closure better is loops. A loop is an execution of code repeatedly until a specific condition is met. Let’s say, a console log that logs the number until the number reaches 5.

Let’s understand how closures work when it comes to loops:

This function is going to the console log “This is” and the current count number that will stop after 5. What exactly is going on here?

countIt is a function that holds a count at 0 in its scope. The inner function increment captures the count variable from the count function, increments it by one, and then logs it to the console.

When we call the function named countIt for the first time, we also save it in a variable incrementbyOne. Next, we have. For loop where we start from 0 and end the loop when it reaches 5. It keeps executing the increment function and this inherent function holds the count value even though the countIt function has already finished execution. We keep looping and the count variables are still captured inside the increment function.

Downsides of anonymous functions

When there are good sides, there are always some bad sides and anonymous functions are no exception.

Hard to debug

One of the bad sides of anonymous functions is a fact that they are harder to find and identify as they have no names, so obvious. When you have issues with the code and something is not working, you can identify these issues with names. Instead of using a name, you might have to add additional comments or explanations in the documentation, so it can be clear for future reference.

When you have a very small amount of code, it might not be that hard, especially when it’s your personal project. However when you work on something much more big and complex, especially if there are a lot of people involved, anonymous function can be more problematic.

Performance

Anonymous functions are also defined and created at a runtime which makes them unavailable during the complication phase. Every time a new anonymous function is created, it creates a new function object in the memory. Even if it’s the same, it will re-create a new object that can lead to too much memory usage and bad performance.

I know, we have to jump from one topic to another once in a while because many concepts are tightly connected to each other. Let me remind you where we stopped. For the keyword function to begin an expression (something that produces a value), it needs to be used in a context(a place in a code) where JavaScript doesn’t expect some statements (commands, actions). Otherwise, the keyword function will start a statement and we need to make sure that we are writing a function in the correct way to receive a function expression.

To achieve this we need to:

Save a function expression in a variable

Or use a function as an IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression)

We discussed how to save a function expression in a variable and that function expressions can be named or they can be unnamed which results in an anonymous function.

Next, we discussed the situation when we could let the function stay anonymous.

Situations when you can use anonymous functions are:

Higher-order functions (HOF)

Closures

We covered both higher-order functions and closures.

Now, we are going to move to callbacks.

After callbacks, we will discuss IIFE so we make use of functions expression and JavaScript doesn’t throw an error thinking it’s a function statement.

Direct and indirect function execution

When we execute functions we can divide them into two groups — direct and indirect execution.

Direct

Direct execution refers to the synchronous execution of the code. When we call one function, then another, and then another, they are not executed all at once. They follow each other synchronously.

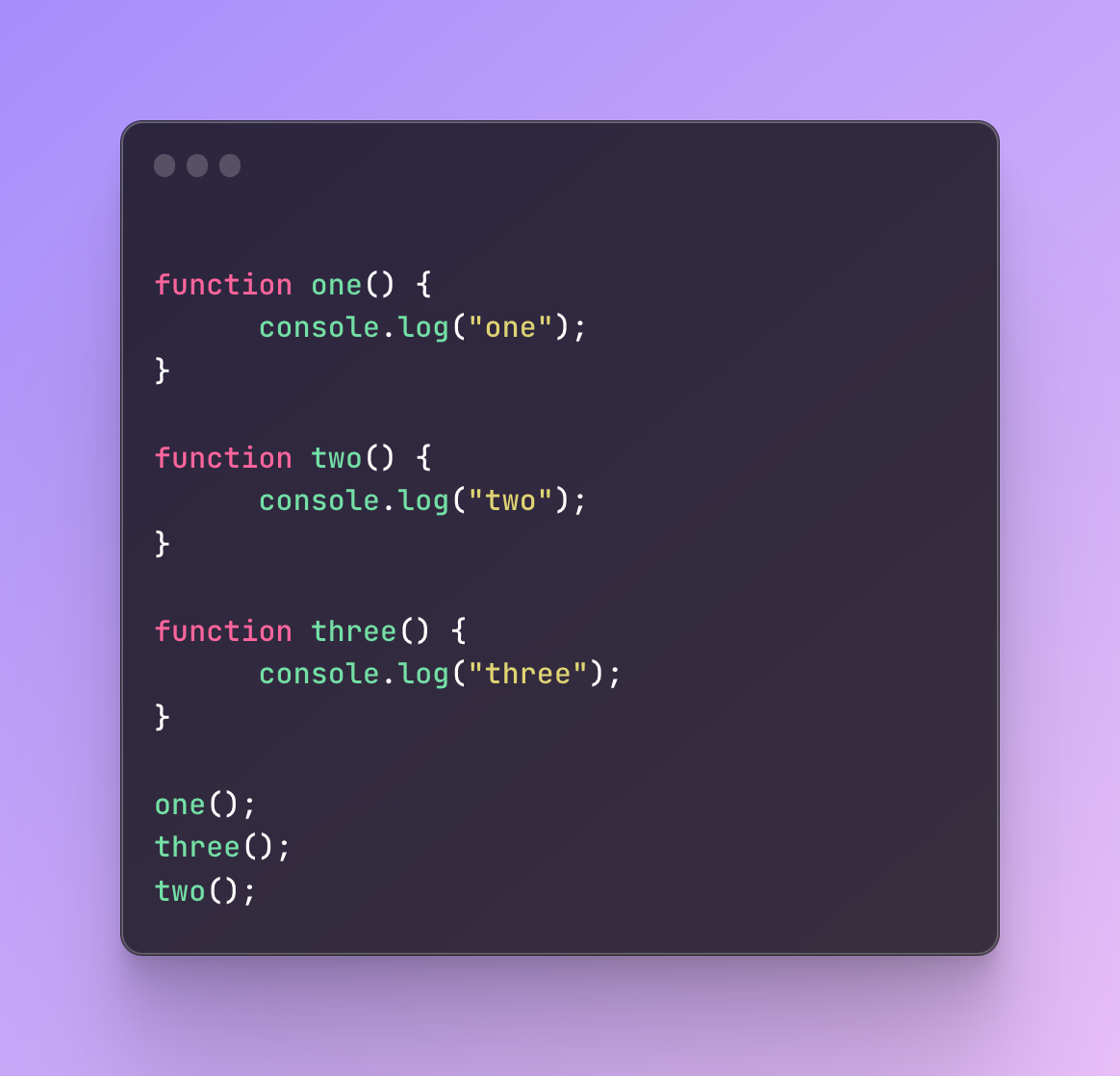

A quick example:

The result will be one, three, two. Because we called them in such order. If I call the third function first, then the first result will be three. Even if I declared it the last. This is called synchronous, direct execution.

Indirect

When it comes to indirect execution, we associate it with asynchronous execution.

Functions are able to go outside the sequence and not depend on the order of execution.

Imagine, a restaurant where we have various functions. You ordering the food, the waiter accepting the order, the cook preparing the food, other people ordering the food — all these are various functions.

Imagine, if all these functions had to execute synchronously.

First, you make the order, the waiter takes the order, the cook prepares the food, you take your order and only then the other person can make an order.

Now, let’s move to the online restaurant where you order food.

On the website, you add food to the cart and send a request for the order. In many applications, when you order food it’s not confirmed right away. It all might happen very fast but when you send the order it’s sent to the server and might take some time to be confirmed. You will either receive a confirmation or a decline, for example.

Orders also have various steps, accepted, preparation status, then sent out, and so on.

While these functions and updates take place you can still interact with the application and do some other staff.

If everything had to be synchronous you wouldn’t be able to do anything until one function is complete.

All this happens thanks to asynchronous JavaScript.

Asynchronous JavaScript

In order to implement asynchronous flow, there are several ways:

Callbacks

Promises

Async/await

Timers

Event loops

Non-blocking I/O (input/output)

Right now we are going to cover only callbacks.

Callback function

The callback is a function that is an argument of another function.

Due to the nature of JavaScript, you cannot call all the functions at the same time. If you remember, for each function we have a separate function execution context and they are piled up on top of each other.

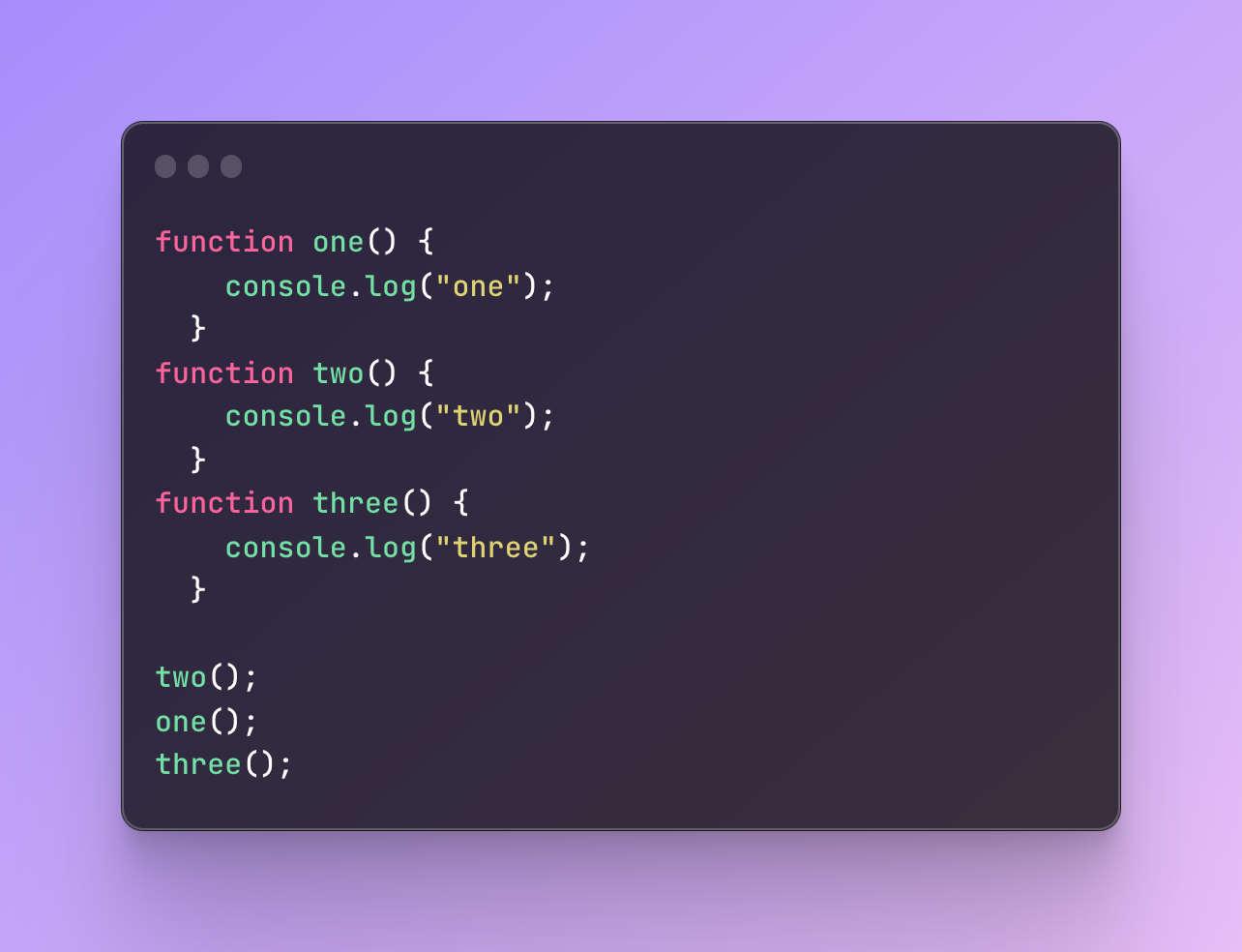

Functions do not execute at the same time. They execute depending on where and how we call them. Can you guess the result here?

I created functions in one order but called them in a different one.

What is going to happen?

It will log to the console numbers two, one, and three because I call them in such order.

But what happens this time?

I call all the functions before I even create them.

Will this throw an error?

No, it will have the exact same result: two, one, and three.

If you don’t understand why, I recommend you go back to the execution context explanation.

The main takeaway here was not the execution context but the fact that the results are provided according to the order I called the functions.

But what if there is a situation when you want to call the function only when the previous function was triggered?

Imagine a real-life example, a restaurant.

#1 You go to the restaurant and the cashier takes your order

#2 After the cashier takes your order, you are given an order number

#3 You take a seat and wait for the order

#4 When the food is ready, the cashier calls you by your order number

Image all these actions are functions. For every customer, the cashier produces actions like taking an order, passing the order so it’s prepared, and calling you when the order is ready.

For the cashier to call you, they depend on another function, which is the preparation of the order. So they wait for another person.

While the food is being prepared and you are waiting at the table, this process is called asynchronous action. While you are waiting there is an order being prepared and this doesn’t prevent the other customer from placing the order.

If all these actions had to be synchronous then when you ordered, the order would need to prepare right away without you waiting, you would need to take the order you made and only then the next person would be able to place an order.

They cannot call you right after you make an order but while you are waiting they are preparing the order. On the other hand, they also need to know how to get back to you while you are waiting at your table. That’s why you have your order number, it’s a way to get back to you.

A callback is a way to call back. So, when the order is ready they use this callback to get back to you and tell you to take the order.

The food preparation function is executing and when it’s done it’s automatically ready to use your order number to get back to you and tell you to take your order.

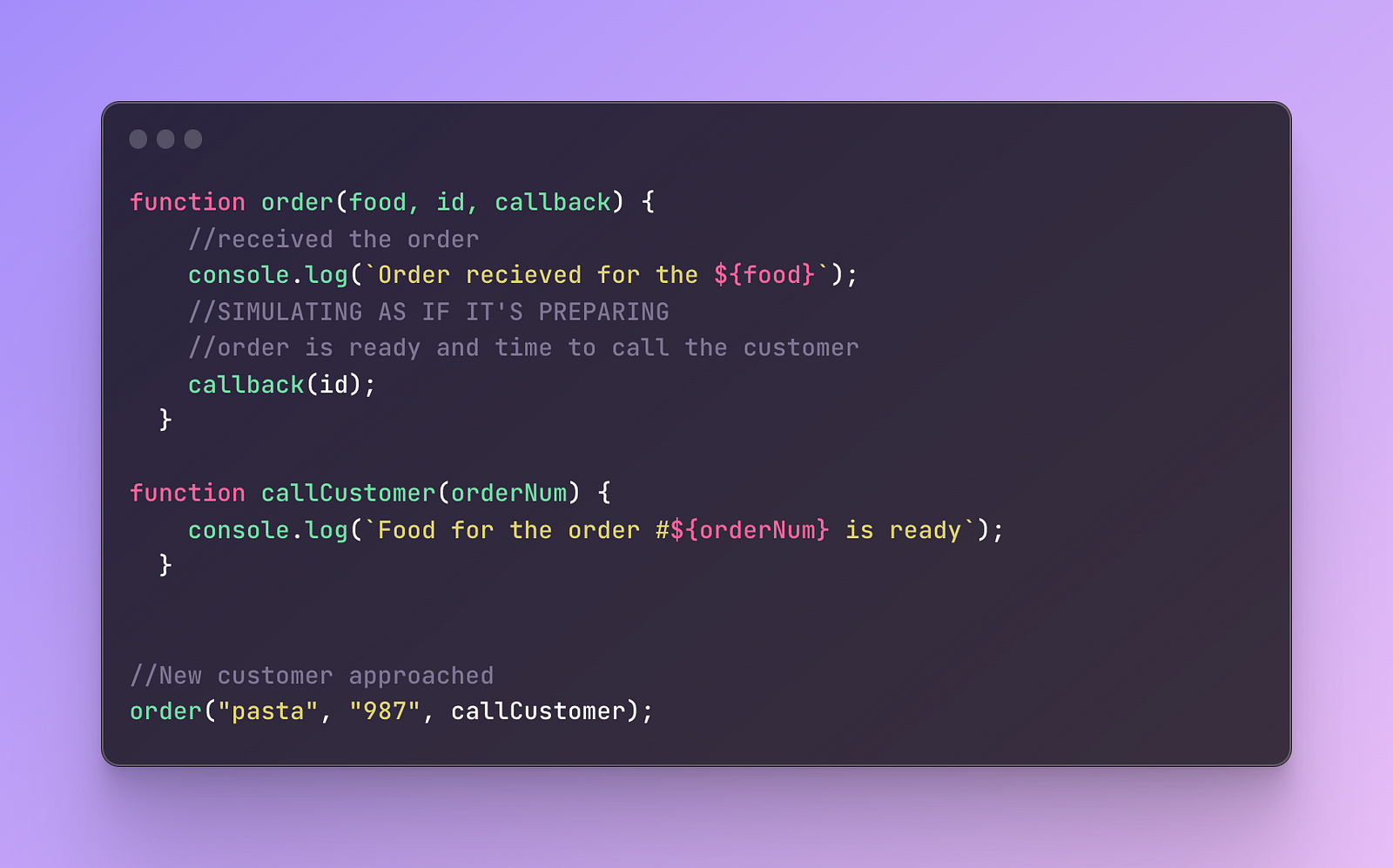

In short, you are attaching one function to another function. Here is a minimalistic example:

To make it easier to understand, start reading from the very last line.

When the customer approaches, I call the function order that has 3 arguments: pasta which is a food parameter in the very first line of the code.

987 is the value for the id and callback is the callCutomer function.

Inside the order, first of all, I wrote that I received the order for the specific meal, pasta in this case.

Then we imagine there was the food preparation and a waiting process.

Then we call the function callCustomer and pass the id. This is what the callback function does. It waits for the preparation of the food and when it’s ready, calls the customer.

Yes, I could write the functions in a specific order and only then add callCutomer in the correct order. But every time I receive a new order, I would have to constantly call the callCutomer function again and again.

Instead, in the order function, I attach functions and I don’t have to control it myself anymore.

Along with the callbacks, often comes an issue with a so-called callback hell which I recommend reading about later on: https://dev.to/catherineisonline/what-is-callback-hell-3emp.

IIFE

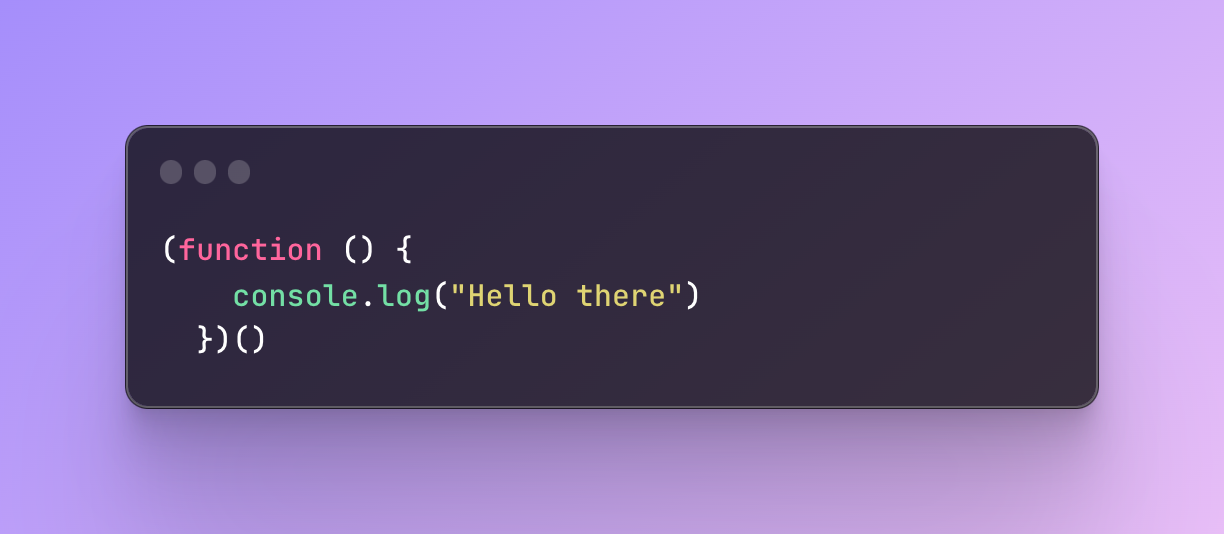

An immediately invoked function expression is a function that is called the moment it is defined. This time, we don’t have to save it in any variables and it will remain an anonymous function.

Previously, we had to use a name because we also needed to call it later on but this time we can make it invoked right away without using any names.

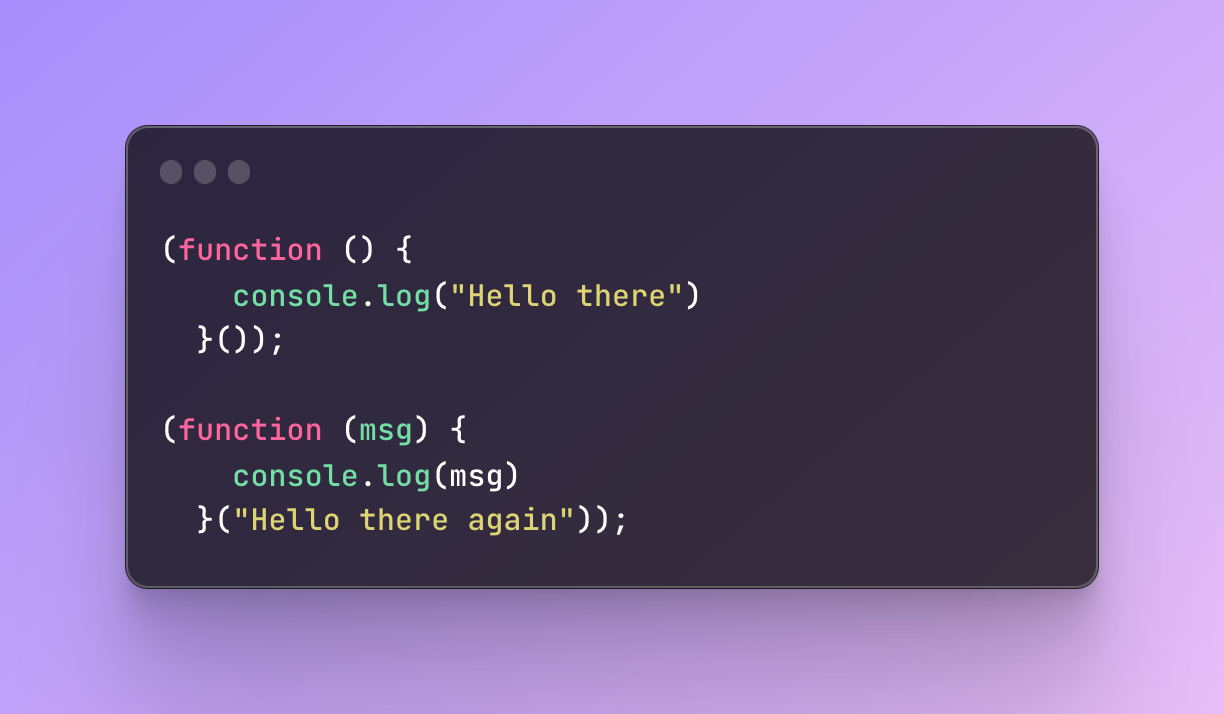

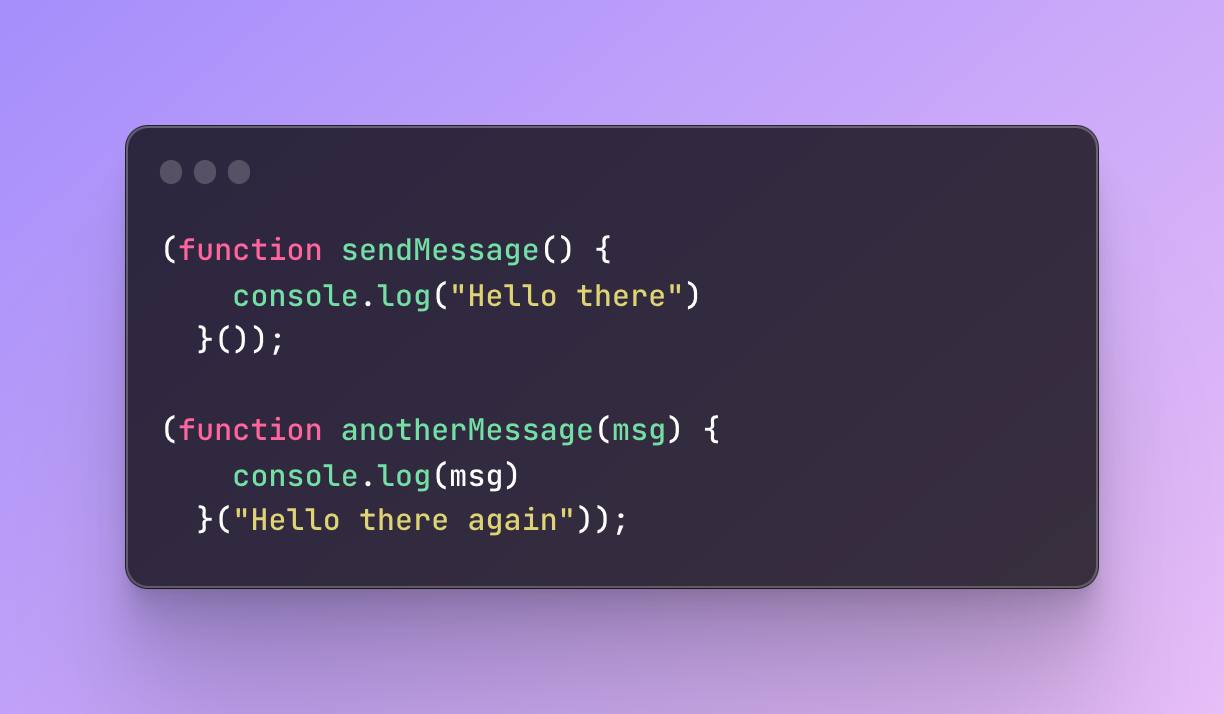

Let’s re-create my send message function one more time:

To write an IIFE, you simply write a function without a name but not to receive an error like before, you enclose it in parentheses so it’s treated as an expression and then you immediately invoke it by passing the argument.

This function will get called right away and we don’t have to do anything anymore.

You don’t have to use any parameters in the function, it’s not mandatory. It depends on what you are trying to achieve.

You can also write the function invocation inside, at the end of the function which is just a preference. There is no right or wrong way.

On the other hand, for IIFE you can use named function expressions as well. Technically they do behave like anonymous functions because they are hidden inside IIFE block but at the same time, it’s not an anonymous function anymore.

Why do we need IIFE?

There are several reasons why IIFE is useful.

- Private scope: Variables that we create will be kind of “stuck” inside the IIFE because it isn’t available in the execution context.

It’s not saved in the global execution context or a function execution context.

This gives you a guarantee that variables won’t be re-used or affected in any way. This is especially important when it comes to var.

When we declare variables with var they can be accessed even outside the function, compared to const, and let that appear much later.

But when it comes to IIFE even var won’t be able to slip away:

In this example, when in the usual function var would be logged twice, this time in the outer console log it will throw an error because it’s closed inside IIFE.

- Encapsulation: Besides the variables, you can also create modules that have both private and public information available in one place. Instead of separating everything, you just save everything in one IIFE.

In the example above, even though I have declared a variable and a function inside IIFE, it returns me an object that will be saved in the messageModule.

In other words, I assigned a return value to the messageModule variable.

This is a way to encapsulate private and public information together.

The way I define variables and a function inside the return statement is also a little different than we have seen before but this topic will be covered later, in the methods section.

- Passing parameters: In addition, you can pass global variables to IIFE and perform operations on them in private.

We pass the answer from the global scope but whatever happens inside stays private.

Let’s imagine more real-life examples.

For example, you are working with a weather API that is fetching data.

You want to create a reusable block of code that also encapsulates this API request.

Doing so can lead to several benefits.

Separating API functions from others can make the code more sustainable and easier to understand. So when you need to find it fast and debug it, the process is much easier. You can also re-use such functions because if you need to make the same API request from different places instead of writing the same request you can create a reusable function instead of repeating a huge piece of code.

This also makes it easier to make updates. If something changes in the API request, for instance, instead of rewriting all API calls, you can only change this modular function that will affect the result everywhere.

When you write reusable functions, they receive input that changes depending on the situation.

Let’s continue with the weather API.

Image that we want to create an IIFE and we are going to pass an API key to it.

By passing this key we are going to initialize the function.

I will create an IIFE step-by-step. First, let’s create the basics:

What did I do here?

I have an IIFE that I am saving in a variable apiRequest. Whatever is in the body of the function will remain private and won’t be accessible outside. Whatever I write in the return statement, will be exposed.

As the argument, at the end of the IIFE, I am passing an imaginary API key so I can make an API request.

Inside this function, I have another function named findCountry that is supposed to receive a country name and log to the console the capital of this country.

This will be done by the imaginary API request.

Next, I expose the same findCountry function inside the return statement and it becomes exposed.

As a result, when I call this function outside IIFE, it will log to the console the result of its body.

Next, inside the IFFE beside the findCountry function I will create another one but this time I am not going to expose it in the return.

What this function does is it receives a country, makes an imaginary API request, and returns some data.

Then, we return the country we searched for and the capital that was returned thanks to the API request.

In the findCountry function, we will call this fetchCountries API, which is currently private, and try to retrieve the information that it returns.

What should happen when we try to fetch countries? The function fetchCountries receives the country information, then it looks for the country and in return gives us the data with the country name and the capital that is saved in the data variable.

Here is the full code:

This way the API request inside the fetchCountries remains private and at the same time we can reuse this function for other APIs.

Please note, this is not a realistic way of making API requests and it’s very minimalistic just to understand how you can use IIFE, not how to use API itself.

This example illustrates how you can make an API request private and safe as well as separate it from other code which will make it much easier to debug it later.

Time to remember where we left off. We started all this when it came to the function definition.

Common ways to define a function:

Function declaration

Function expression

IIFE

Methods

Function constructor

Arrow function expression

Generator function

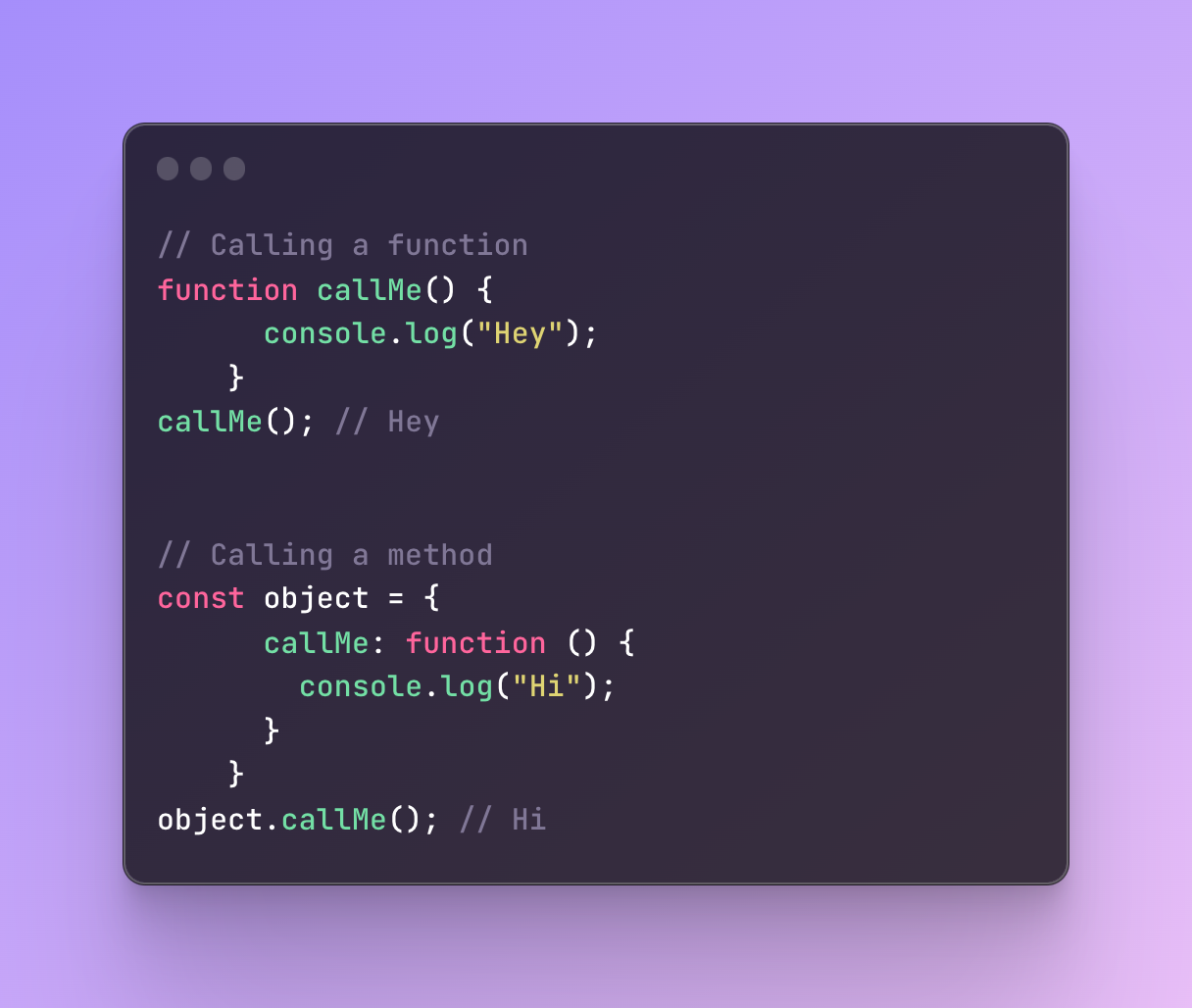

Methods

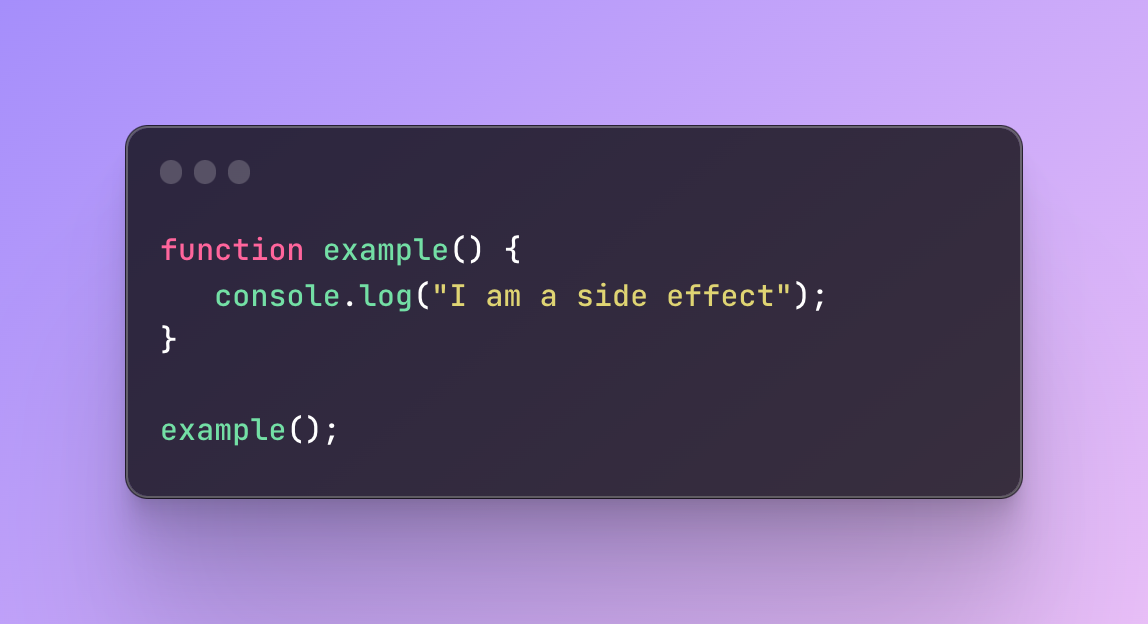

Methods are also functions. A function is a block of code that is supposed to perform a specific task(s). A method is also a function that is supposed to perform a task(s) but it’s associated with an object. In other words, methods are also functions but they are properties of an object.

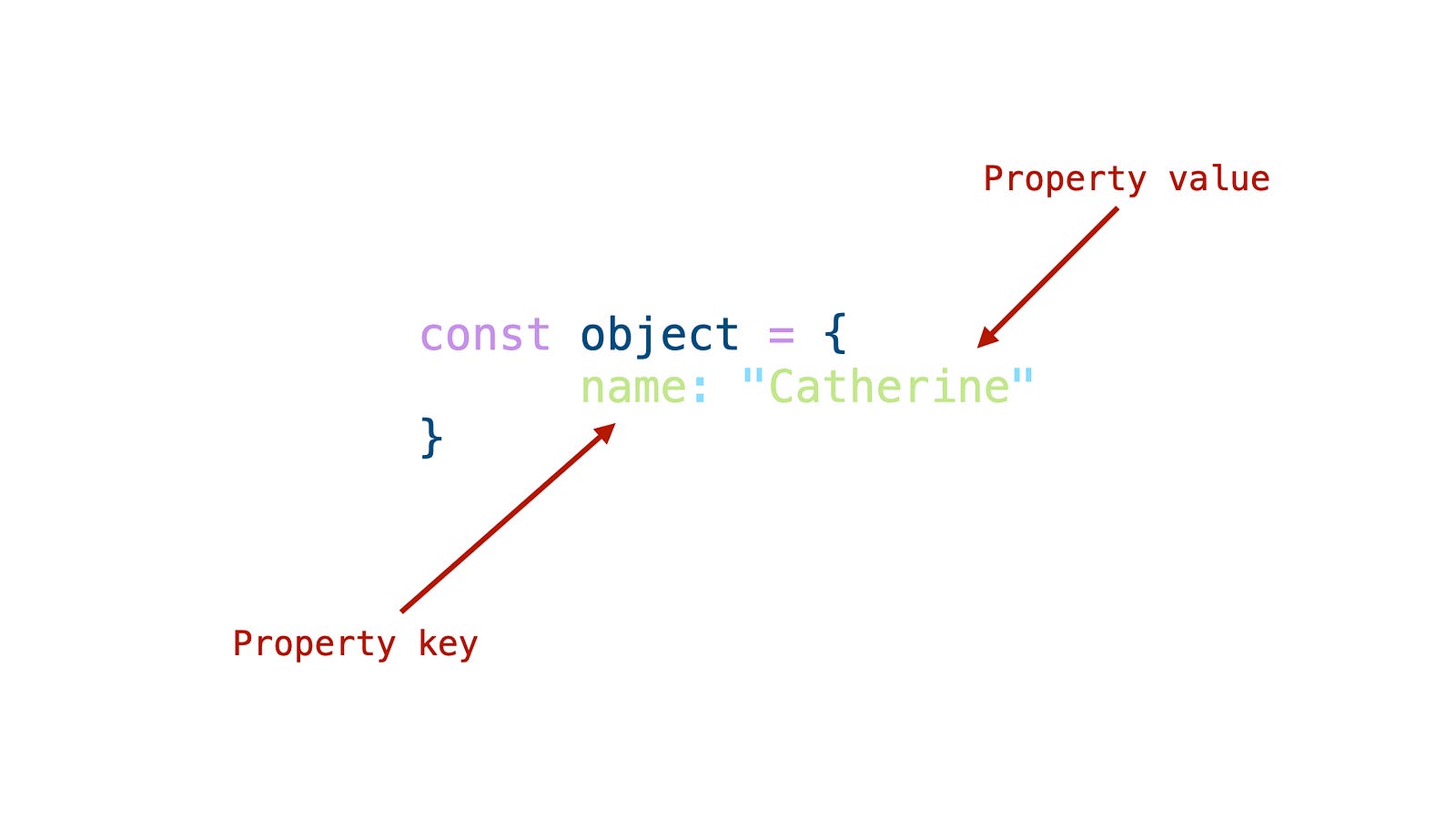

What is a property?

Property is a key-value pair of an object, in other words, objects are collections of these properties.

Another difference between a function and a method is that functions can exist on their own, they don’t have to be attached to something else. The only thing they are attached to is the global object.

Methods however cannot exist on their own and they need to be a property of something else, in this case, objects.

They define the behavior of the object they are located in and operate on the other properties within this object.

That’s why calling functions and calling methods are also different.

To call a function you simply use the name of the function however to call the method, you need to use the object name along with the dot notation.

Built-in Methods

Now, that we understand what methods are, time for built-in methods.

Built-in methods are pre-written methods that are part of JavaScript.

These methods perform regular tasks without the need to write everything from scratch.

Built-in methods save a lot of time and provide guaranteed functionality.

When you create a function yourself, you might miss out on something but the built-in methods are already there, ready to do the job for you.

On top of that, these methods are pre-compiled and optimized meaning that they have better performance. In JavaScript, there are various built-in objects that provide various functionalities and they also come along with their built-in methods.

There are a lot, really a lot of objects that you can read more about on MDN.

We are not going to cover them all today but for better understanding let’s go through several basic ones which you will 100% encounter with.

String built-in method

There are a lot of built-in string methods which have various purposes but let’s say we have a string and we want to find at what index a specific letter is located. Instead of creating a function ourselves, we can use a built-in method indexOf().

Here is an example:

There you go, it’s so simple. We took the string name and with the dot, a notation used the method name as well as passed whatever we were searching for.

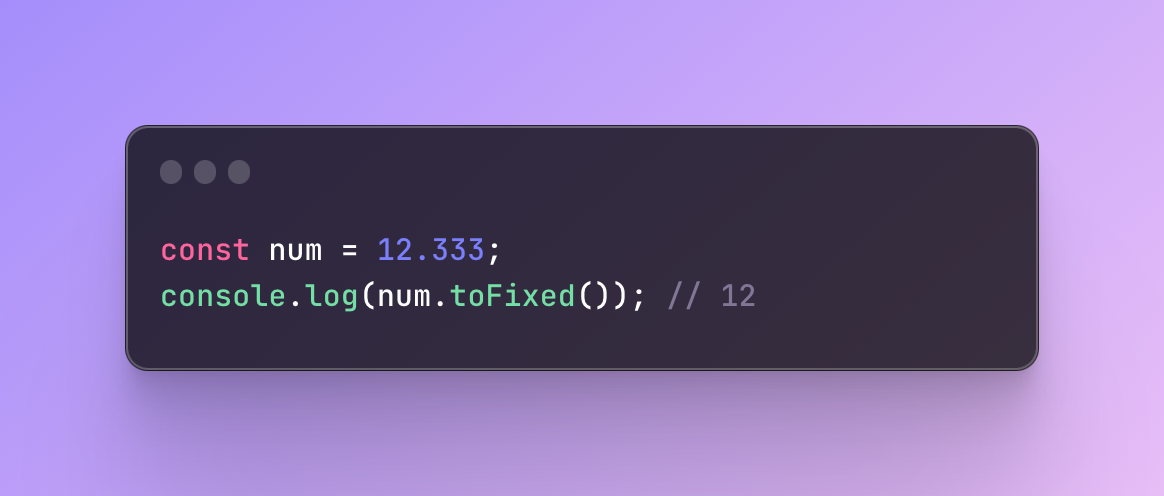

Number built-in method

There are tons of useful methods that work with numbers.

One of them can receive a number and return a fixed amount of fractional part. So if I have 9.9 it should return 9, if 1.145 it should return 1.

You simply indicate the number you want, add the method, and receive the result. No need to create any logic yourself.

If you want to read more about other methods I recommend you to read my String methods cheatsheet and Number methods cheatsheet.

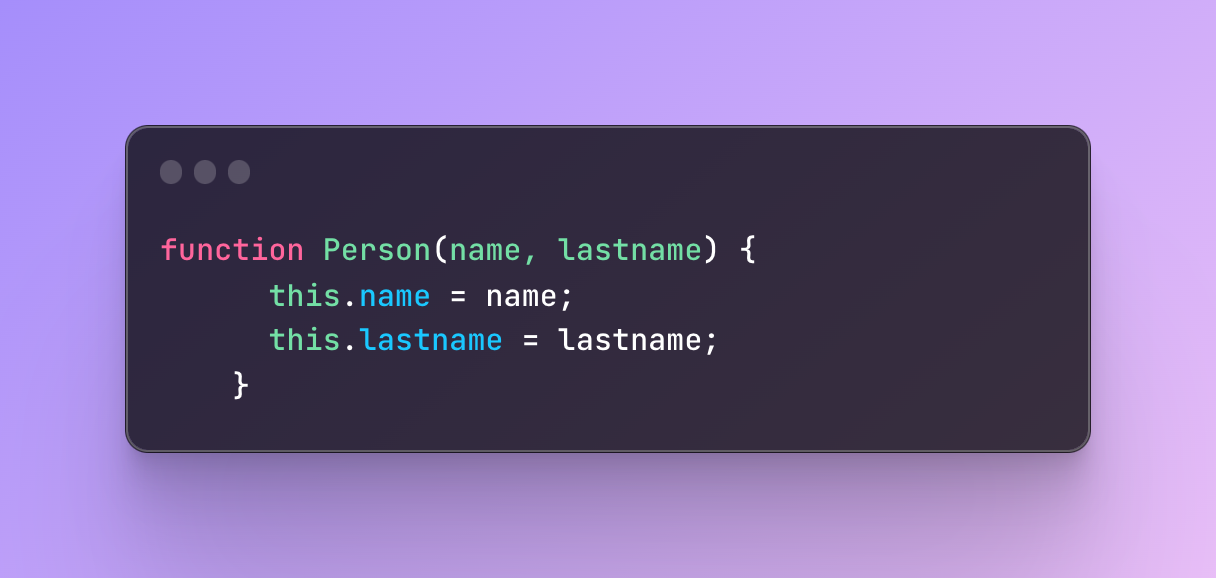

Constructor functions

A constructor function, also known as simply a constructor, is a special function that creates an object.

You can create multiple instances (objects) of a specific type where each instance inherits properties or methods that were defined inside a constructor.

To differentiate regular functions from constructors, you should start the name of a constructor with an uppercase letter.

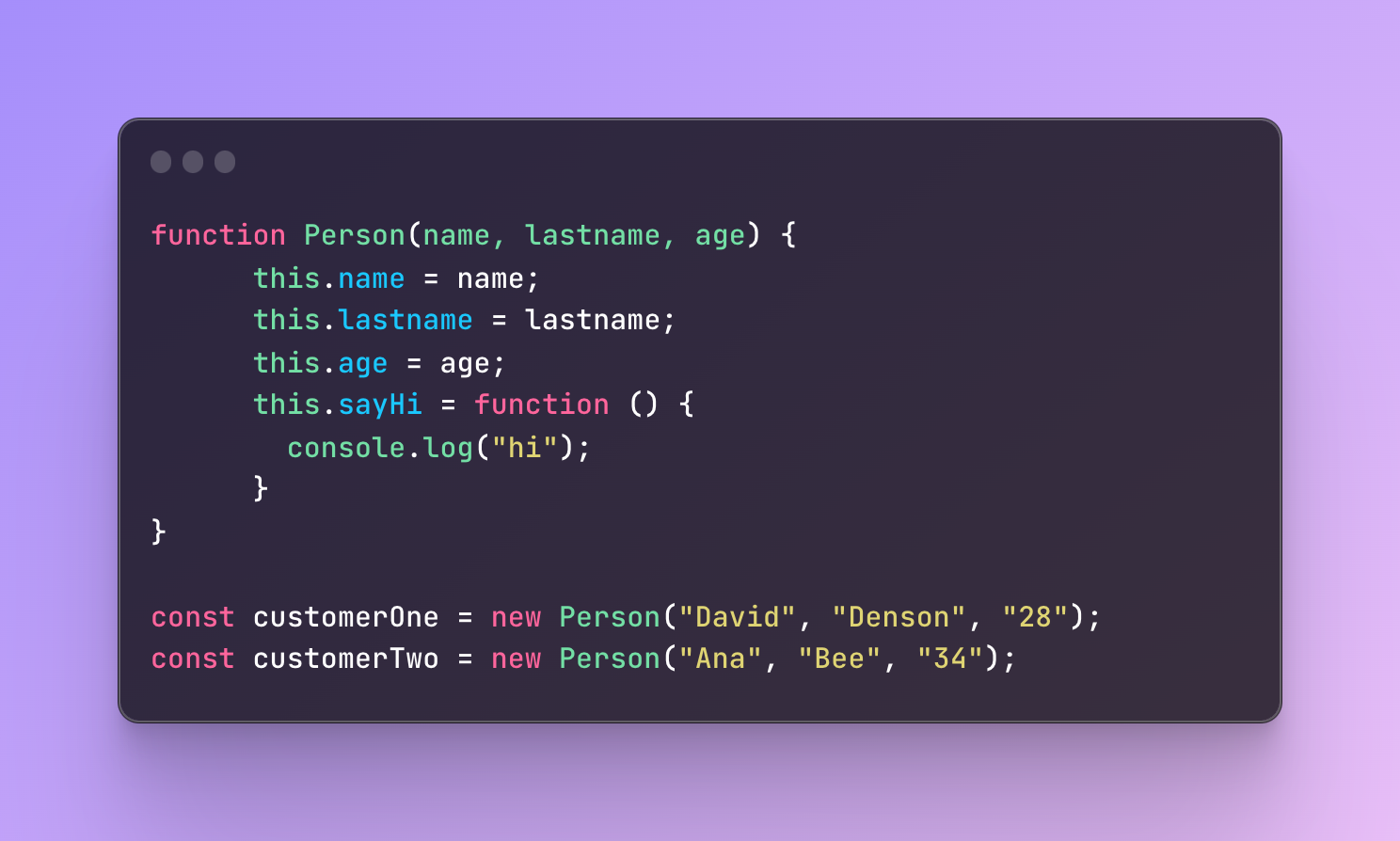

In this example, we created a constructor function Person that accepts two parameters and then assigns them as properties.

The function above is just a skeleton, a template for our future objects. With the help of it, we can create new objects by using the keyword new and the constructor function name.

This way, we created two new customers by using the template. We do not have to repeat many times the same parameters or repeat the properties every time we create a new customer.

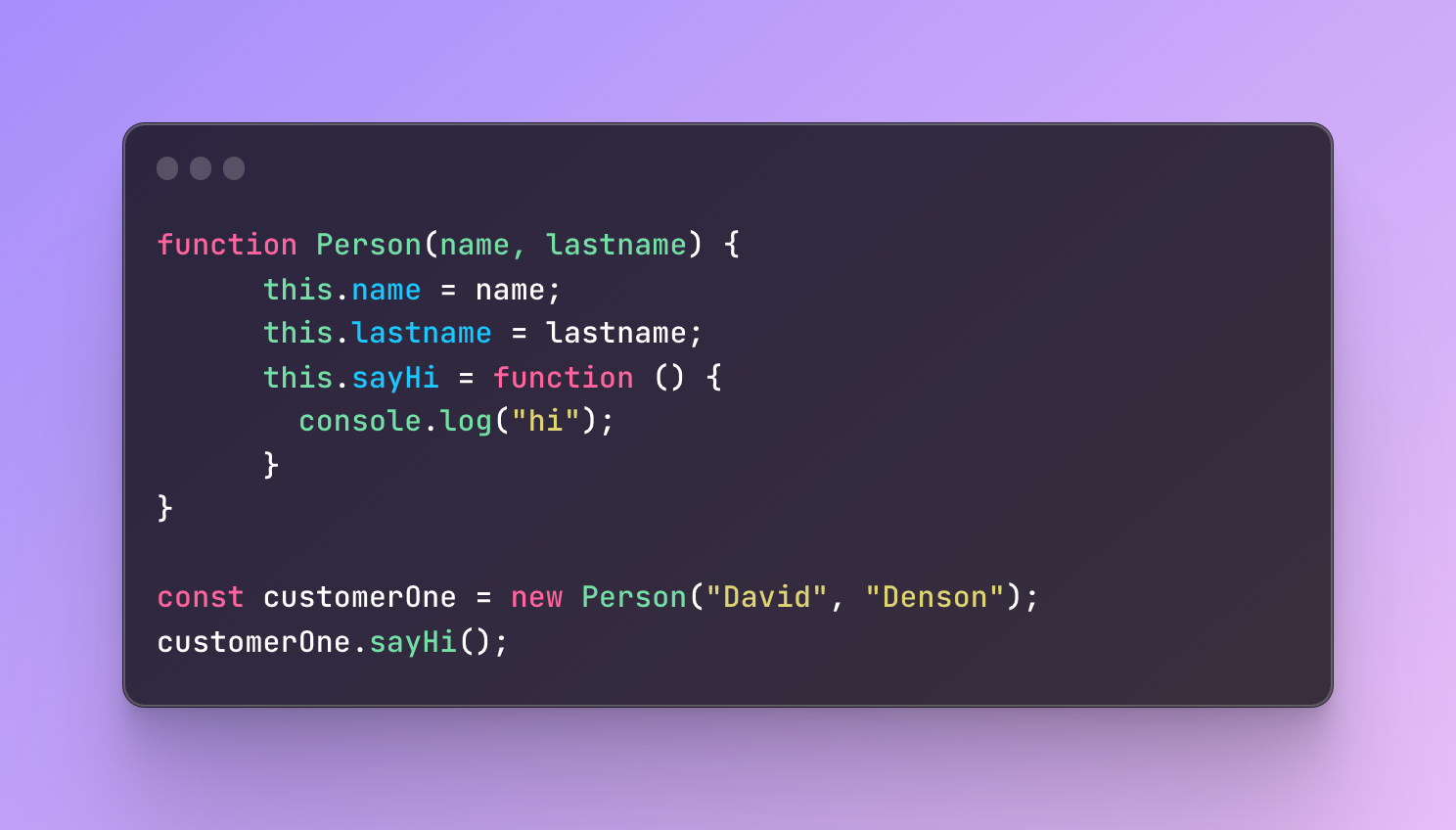

The keyword this will refer to the object when we create it. If you are not familiar with what this does, I will come back to it during arrow functions.

As properties, you can also add various methods that perform any logic you need. Anything defined within the constructor function will be inherited by newly created objects and they will have their own copy.

In this example, when we created customerOne we didn’t create any methods for it. But considering that it was created with the help of the constructor Person, it should inherit its methods.

What will happen if we try to call the sayHi method for the customerOne?

It will log to the console “hi” because it was inherited automatically.

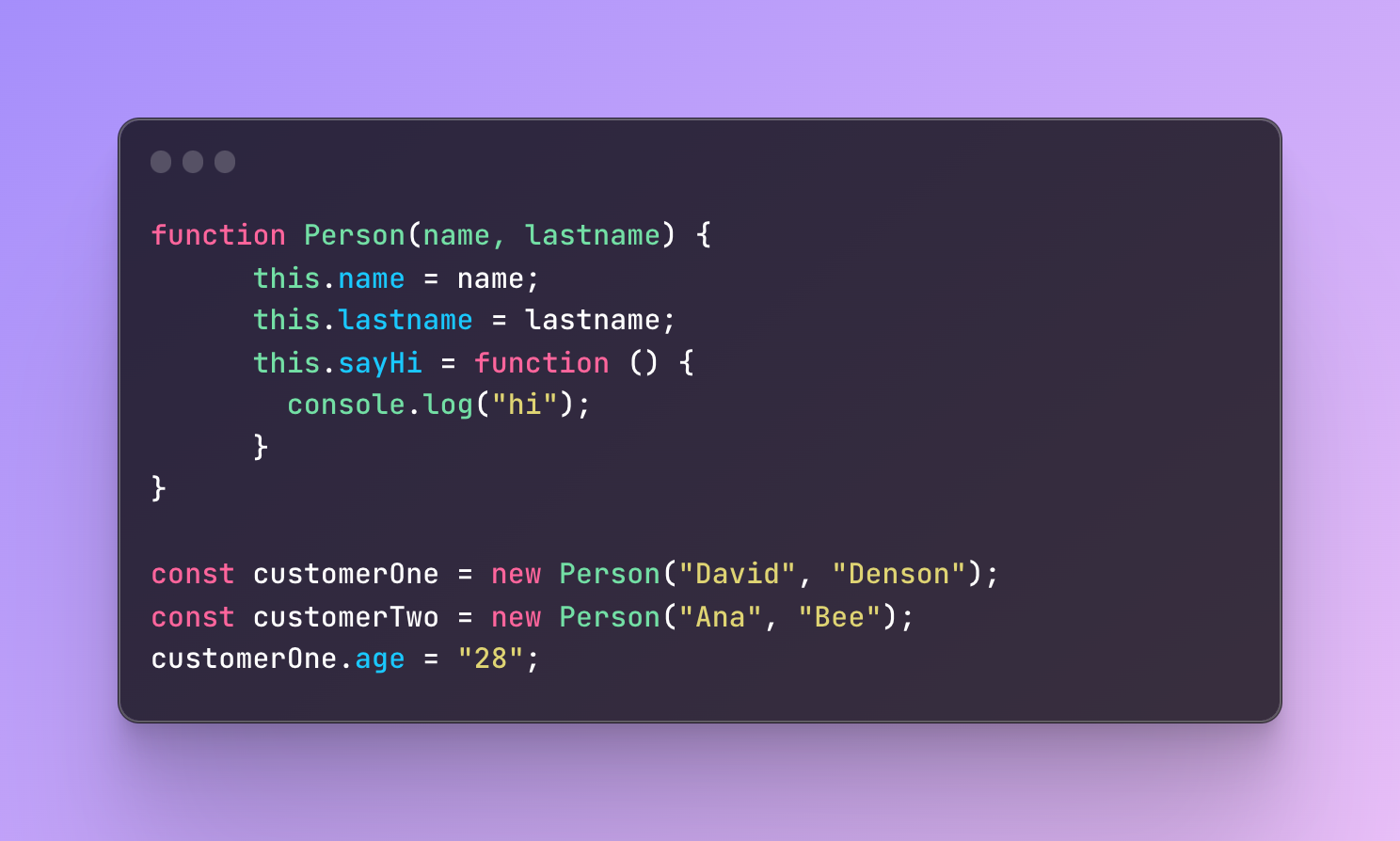

After you have created a new object, you can also add new properties to it, however other objects, even if created from the same constructor, are not going to inherit this property.

To create a new property you can use a dot notation, the name of the new property, and equality to the value.

In this example, we added a new property called age to the customerOne. However, this property will belong only to the customerOne and will not be inherited across other objects created from the same constructor.

To create a method for new objects, you can follow a similar structure.

If you want all the objects to inherit the properties, then the property needs to be added to the constructor function. On the other hand, you cannot add properties like you can with regular objects. You need to write it inside the construct function directly.

Let’s add the age to the constructor:

Every object will have an age property now.

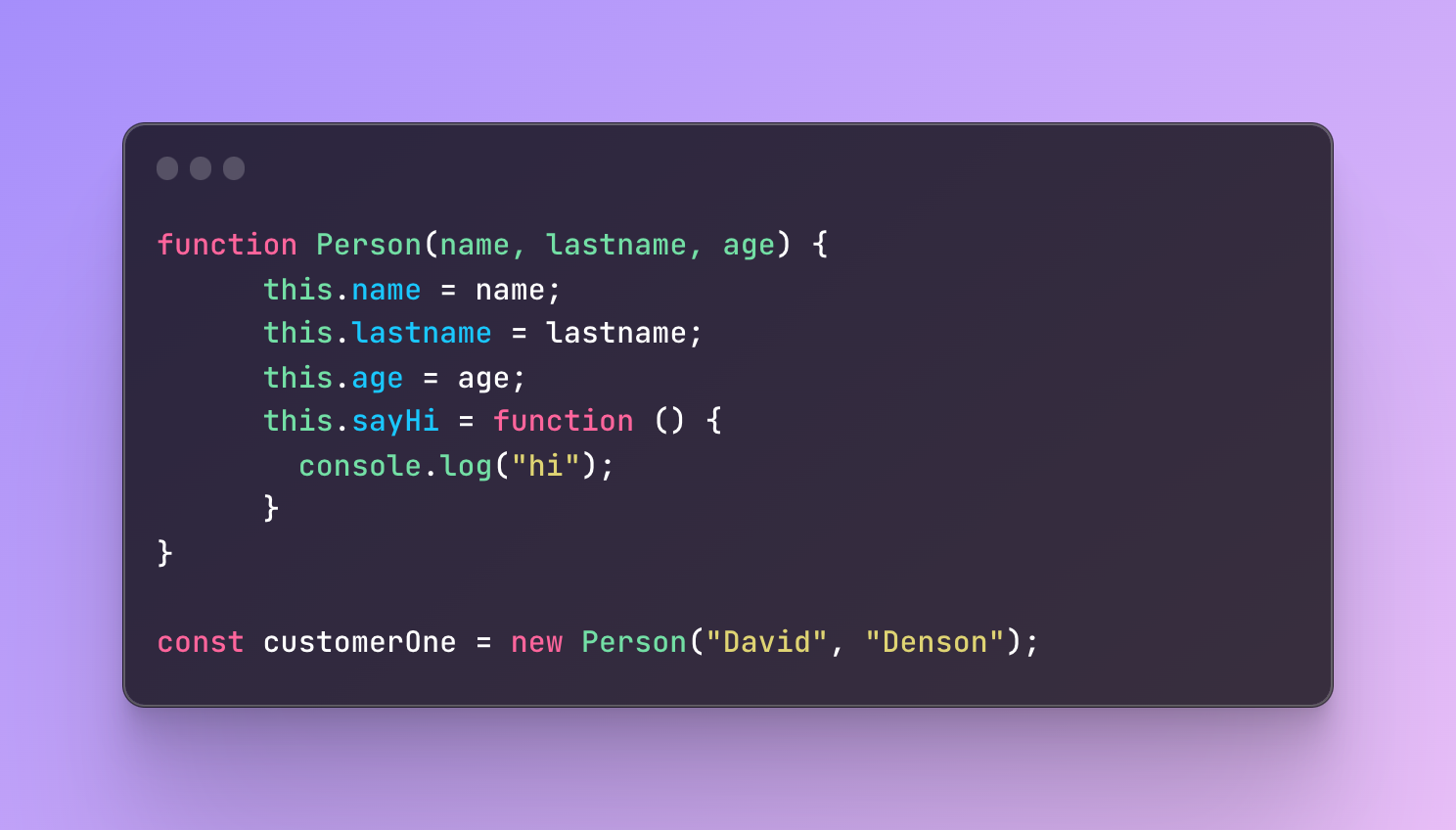

An interesting question — what happens if I don’t include age value when I create a new person?

Let’s imagine a new customer registered and the age field is not required so the customer skipped it. Will the customer be able to register or what will they see in their profile?

If you try to log to the console cutomerOne, it will show that the age is undefined.

So, this might be good because we didn’t receive any error.

But when a customer goes to their profile they will see in the field of age a value undefined. This is not what we want. It would be better if we could make it more clear. Instead of undefined we can give it some default value so it’s less confusing. Options are endless but let’s just make it “-“ if the field ends up being empty.

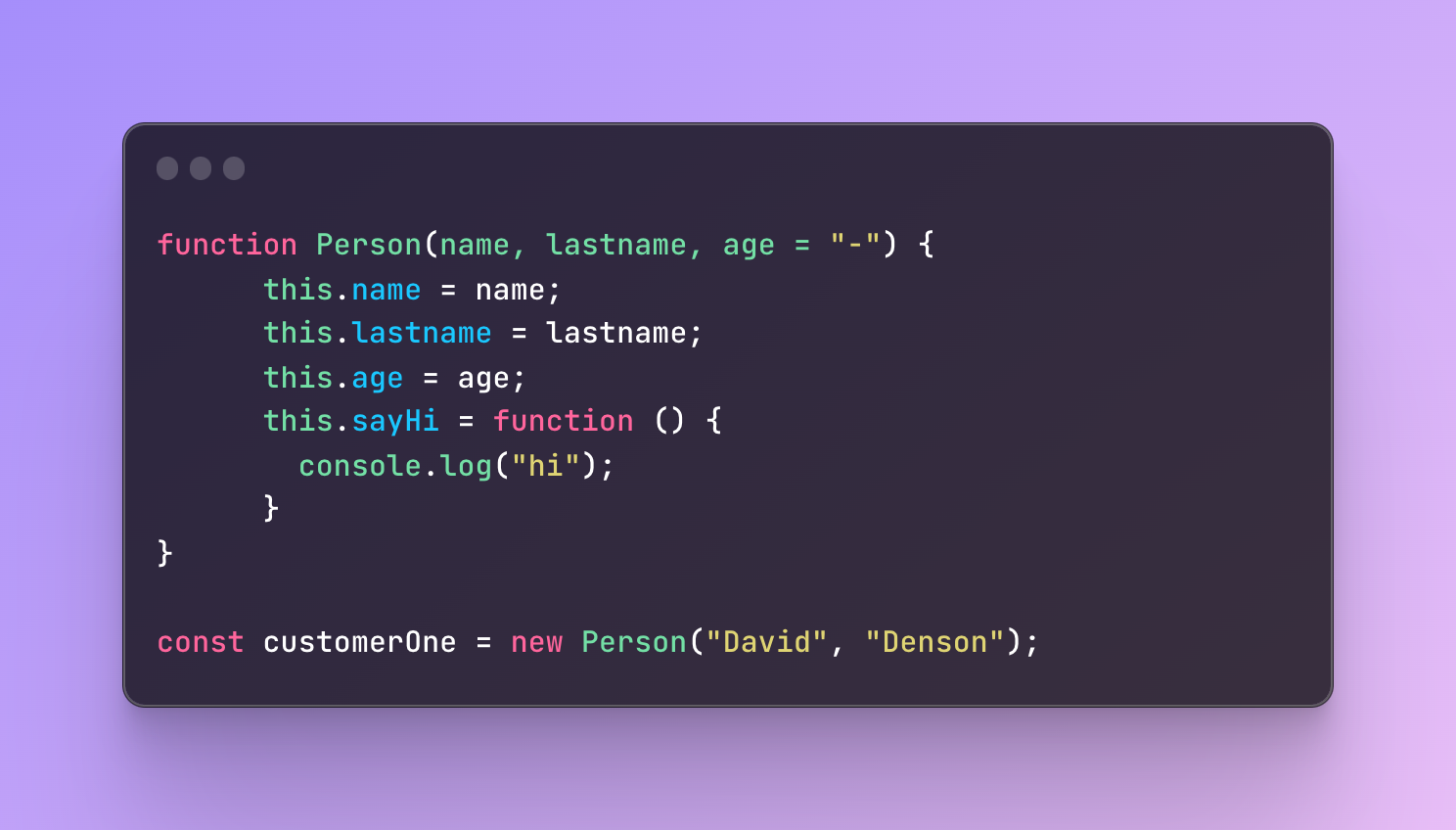

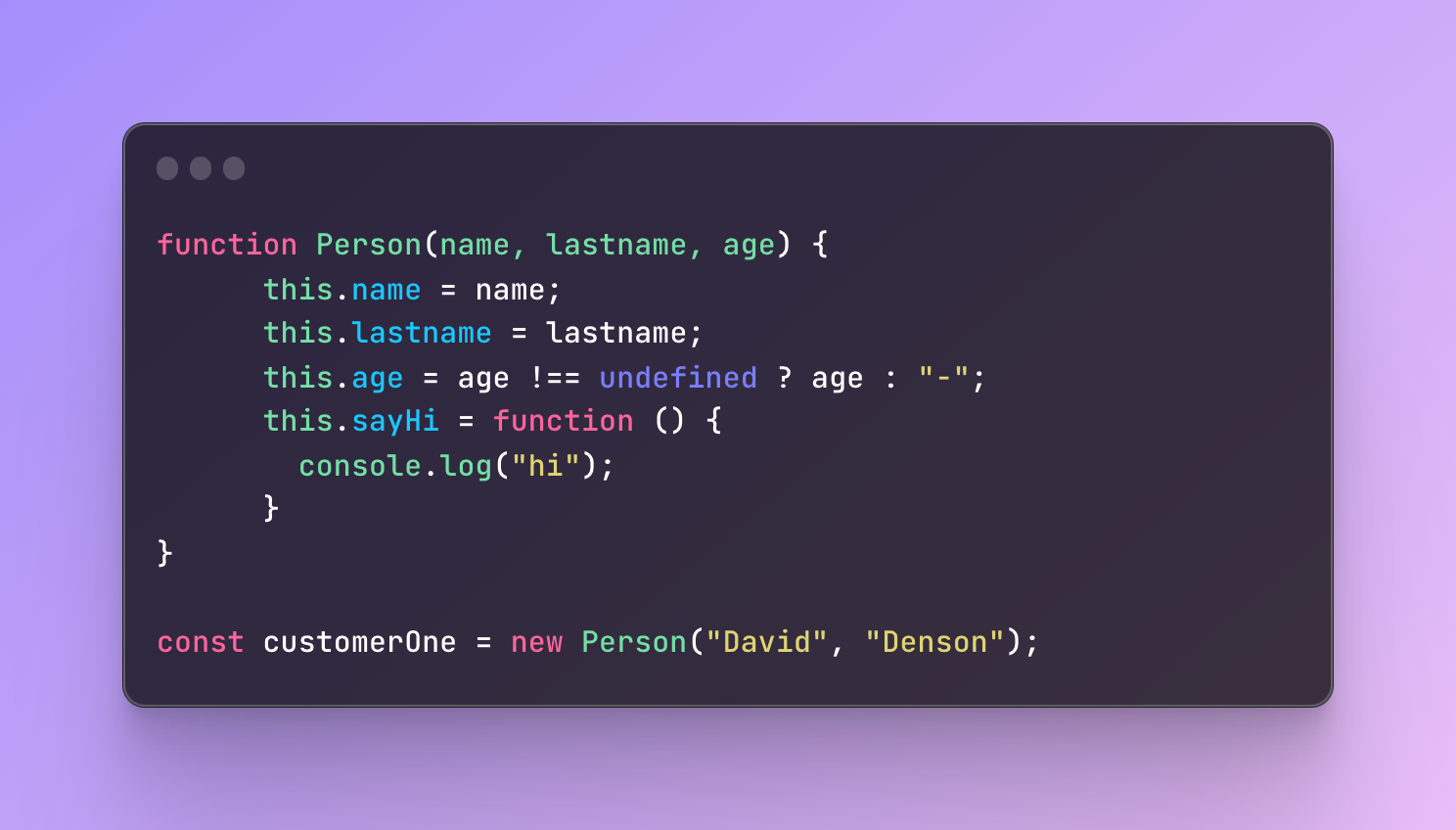

This time, in case the customer skips the age field, the default value will be set to “-“. This is a more modern way but alternatively, you can also conditionally check if the value is undefined and set a default value if so.

What we did here is that we set the default value conditionally. The age property will equal to age parameter if age doesn’t equal to undefined. If it does then the value will equal to “-“.

As a result, constructor functions are reusable object templates that share the structure and make it easier to create objects of similar “type”. The real-life examples can be accounts of customers in the bank or e-commerce website where the structure is the same across all customers.

Time to remember where we left off. We started all this when it came to function definition.

Common ways to define a function:

Function declaration

Function expression

IIFE

Methods

Constructor functions

Arrow function expression

Generator function

We already covered function declarations, function expressions, and IIFE. Time to understand arrow function expressions.

Arrow function expressions

Now that we know what function expressions are, it will be much easier to understand what an arrow function is.

An arrow function is a more modern alternative to traditional function expressions.

The benefits of the arrow function are:

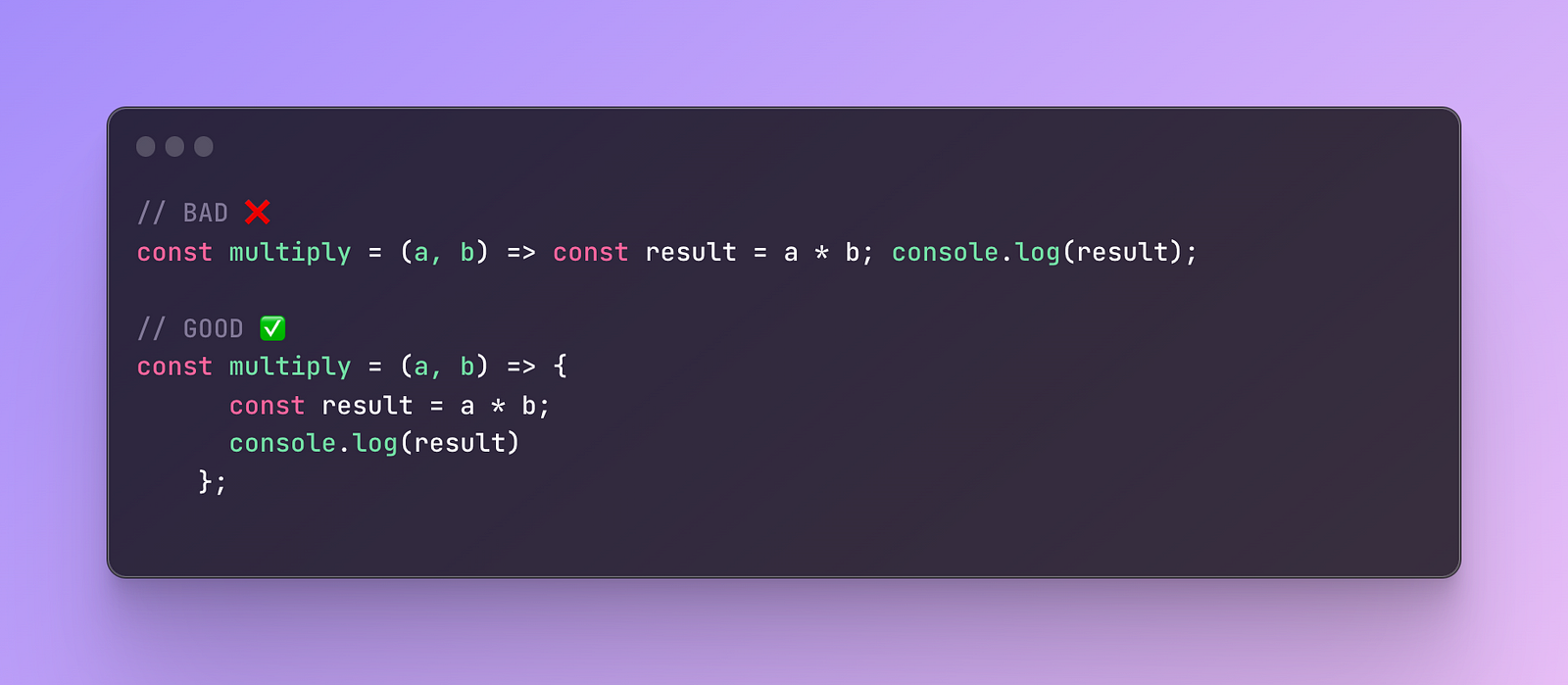

- Readable, simple, one-liner syntax: You can omit the keyword function, braces, and even return.

It’s important to note that you cannot always avoid braces and it can be done only when you have one statement in the function body.

Otherwise, you have to use braces.

When it comes to arguments, you can avoid wrapping an argument around curly braces. But you can do this only when there is just one argument.

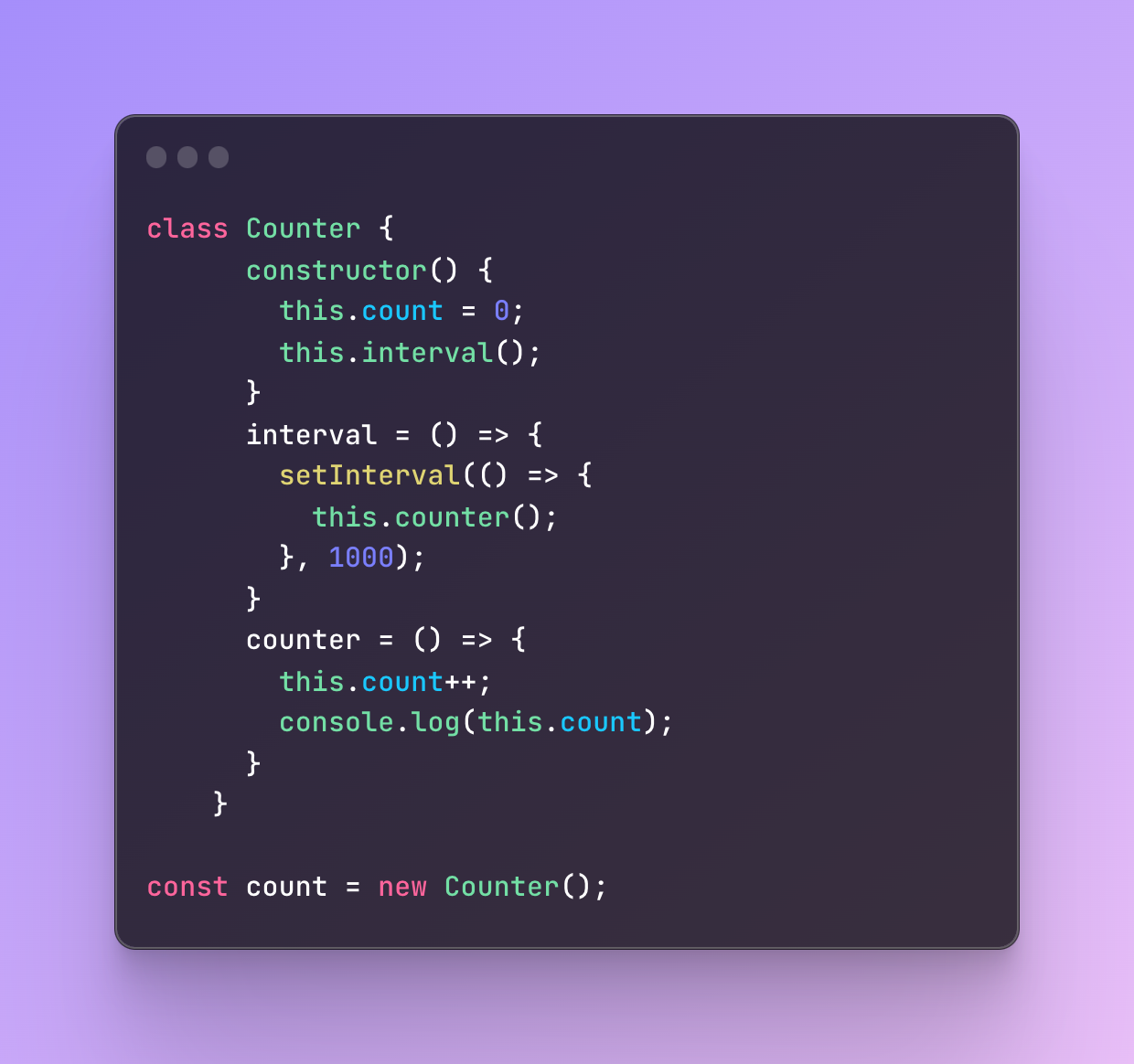

- Lexical “this” binding: Arrow functions don’t have their own “this” context and inherit it from the scope they are located in. This eases the usage of “this” when it comes to callback functions.

Here is an example of an arrow function we use in a class:

We have a class Counter that has a method counter.

In this method, the count is increased but 1 every time it’s called and we log the current count to the console.

It executes with the help of an interval function that is called in the constructor all the time.

The interval has a callback function that runs only after 1 second. In this case, both interval and counter are arrow functions and they use the “this” keyword.

Traditionally, this refers to the context it is used in. In the case of arrow functions, this refers to the context it is surrounded by, the Counter class context, simple as that.

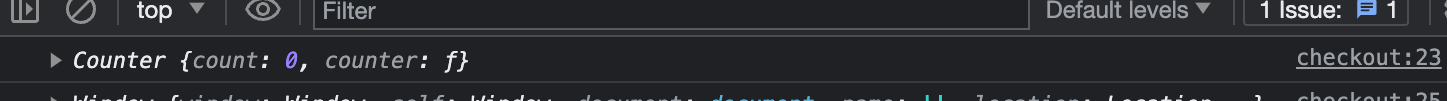

What happens if we transform the interval function and a callback function inside it to the regular function?

I changed only the interval function and it’s not an arrow function anymore.

For the purpose of understanding, I am going to change the code a little bit.

First, when the interval function runs, I log to the console the this, so we can understand what it refers to.

Then, I log to the console another this keyword inside the callback function that runs after 1 second.

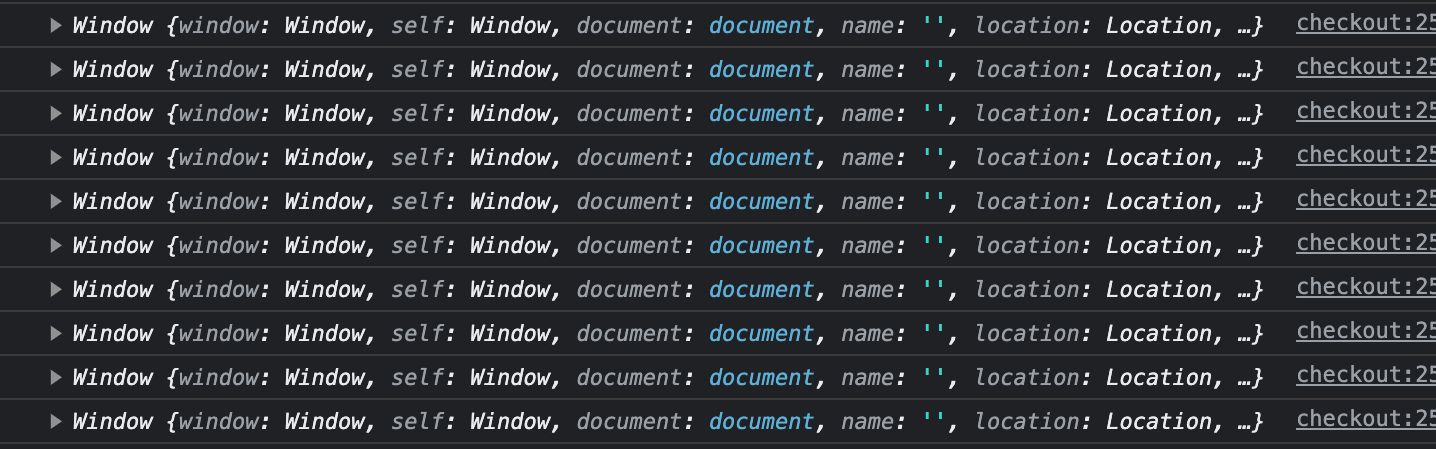

Would this return different results?

The first this:

The second this:

As you can see, the first this refers to the Counter context but the second one to the global object (window).

But why?

When it comes to functions, this keyword can act differently depending on how the function was called. In this case, our concern is callbacks which we used in an object.

When JavaScript is read by the browser engine, it creates an execution context like a global execution context, and then for each function, there is a function execution context.

All this is piled up on top of each other creating a call stack.

If it’s a regular function and you call it in a regular way it will execute according to the order you wrote it.

In every execution context, we have various information about the function, one of which is the information about the this keyword as well as where this function was called from.

Callback functions are the functions passed into the regular functions that are also called higher-order functions.

They have priority just like variables, they are first-class citizens.

But the callback function is a lucky friend who was invited to this special party. And how the party will go depends on the higher-order function, not the callback function.

And the THIS party is no exception.

Meaning that in order to understand what this keyword refers to we need to understand who the main character is.

In our case, the callback function is called inside a function called interval. The interval is called in the constructor. The this keyword in the constructor refers to the instance of the Counter class.

The this will be automatically bound to the Counter so that’s why the first this refers to the Counter.

When we call the setInterval callback function it doesn’t have its context and when there is no context. As a result, a default context will be set to a global context.

If we use strict-mode then instead of global context the value will be set to undefined.

Let’s write the same class again but this time I will try to implement the counter like before but again without an arrow function:

What will happen?

It will throw an error because this refers to the global object and it cannot find a counter function.

When the execution context of the interval function has ended, the callback function comes with a little delay so it cannot associate itself with the context of the function it is located in.

When we use an arrow function, the this keyword would bind to the lexical scope, the scope it is surrounded by.

But what did people do before the arrow functions?

Obviously, there are other solutions.

Some people don’t want to use the arrow function even now and prefer other options.

To solve this issue you can simply use a bind() method. This is a method that can manipulate what this refers to.

Considering that our main goal here is to cover functions, I recommend you to read more about bind methods where I also expand objects.

- No arguments: Arrow functions don’t have their own arguments as they inherit them from the surrounding scope.

This helps to avoid any issues with variable shadowing.

Cons of an arrow function

Even though we discussed some benefits of arrow functions and how the “this” keyword works, it can also be problematic at times.

There can be scenarios when we need to access the function’s this keyword.

Before going further, make sure you have read about the callbacks, methods, and constructor functions.

In what scenarios do we need to access function’s own this?

- Object methods

When it comes to methods, we usually have the need to access other properties of an object where this method exists.

This means that when we attempt to use the this keyword, the arrow functions will cause an issue.

Why?

Because this keyword will not refer to the surrounding scope of this object but to the global object instead.

As a result, using arrow functions isn’t a good idea when it comes to the methods.

Here is an example for better understanding:

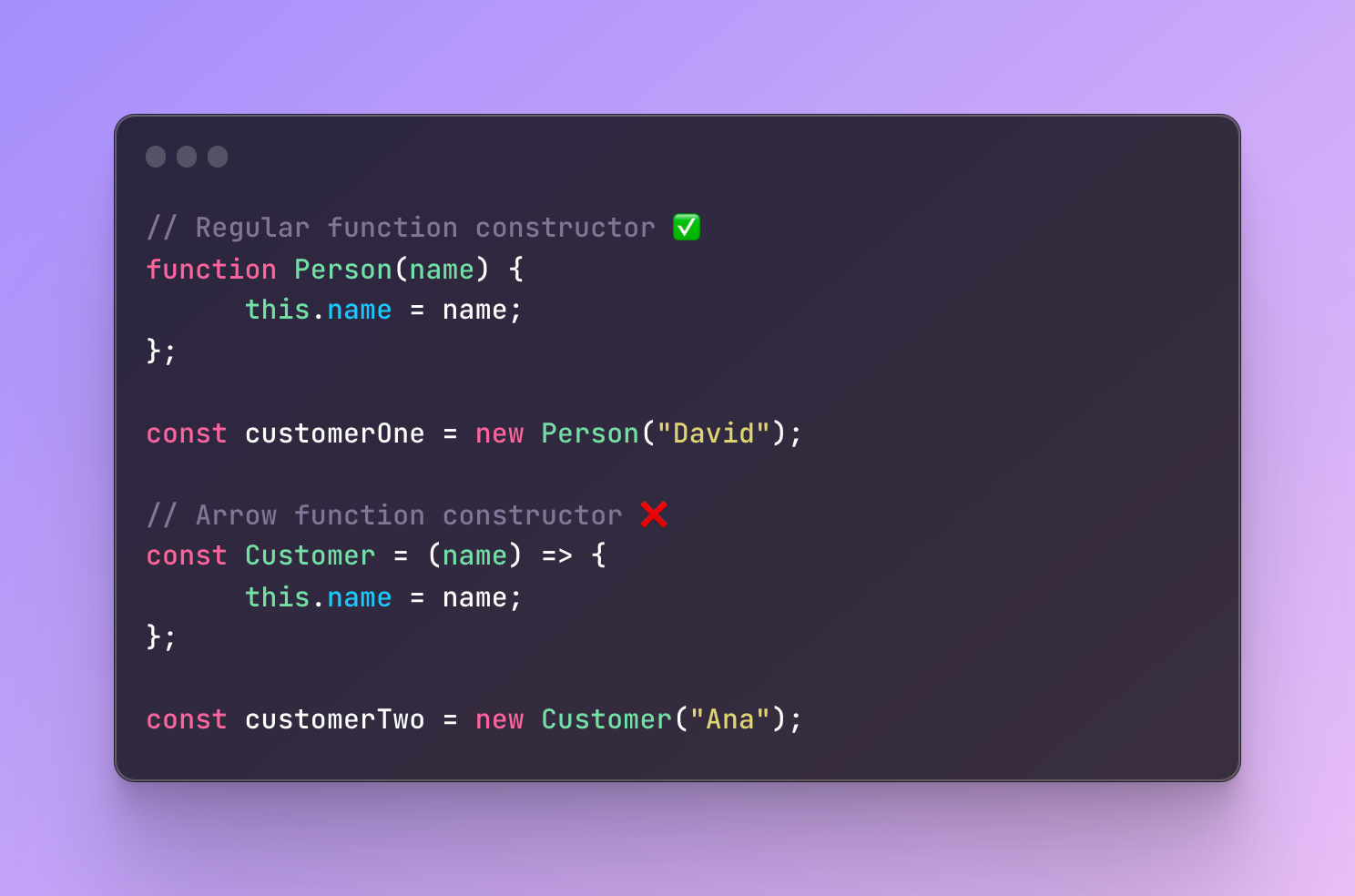

- Constructor functions

A similar issue with this keyword takes place when it comes to the constructor function.

That’s why we don’t use arrow functions in constructor functions as the reference of this keyword is very important.

If we try to use an arrow function in the second example it will throw a TypeError that “Customer is not a constructor”.

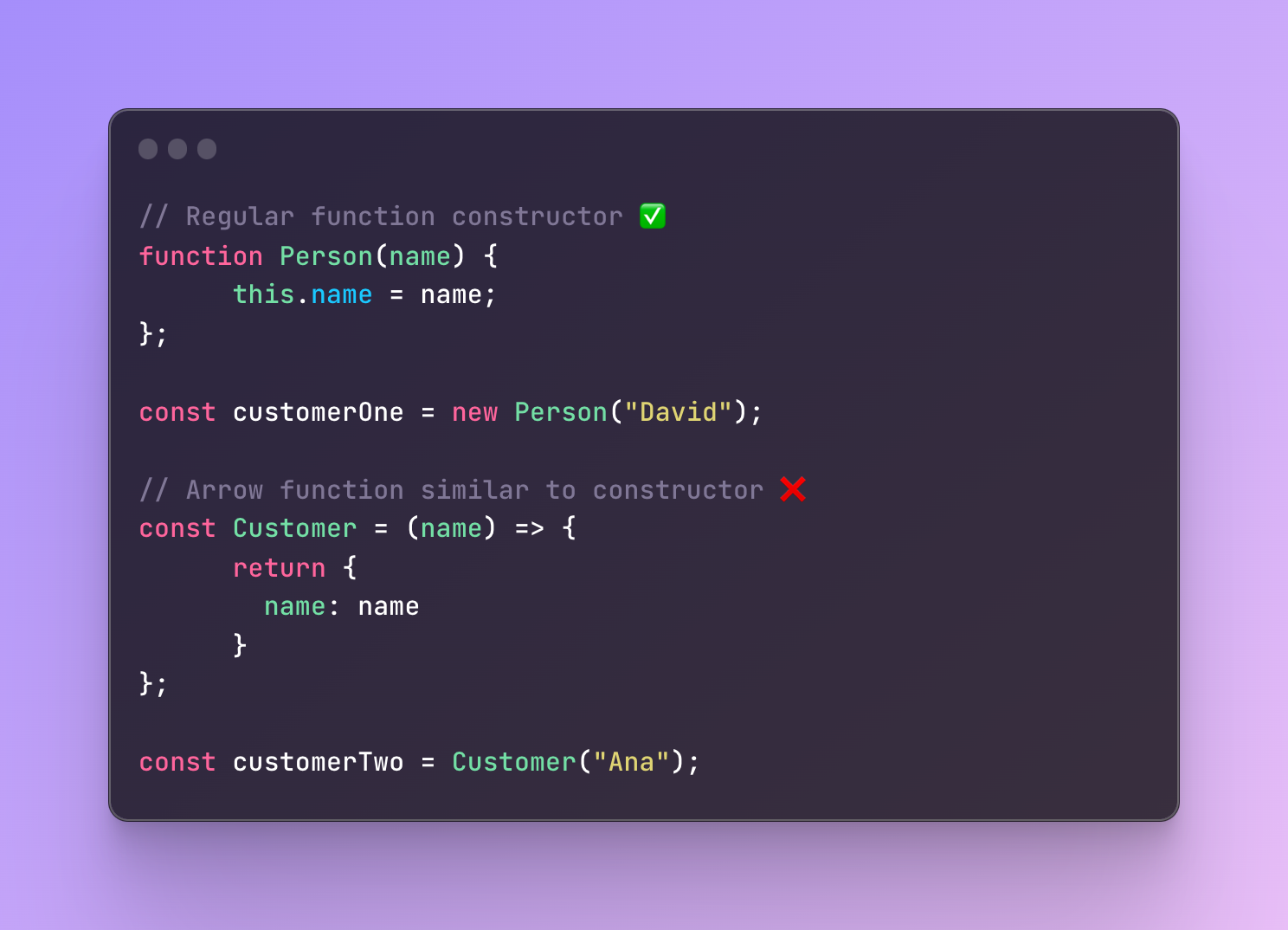

We can rewrite the function and keep it an arrow function. We can make it look like a constructor however it won’t have all the key features of a constructor.

- Callbacks

Just like in methods, similar concerns apply when we use callback functions.

As long as a callback function is surrounded by a function declaration, it will work fine. Even if the callback function itself is an arrow function.

But if we wrap a callback function with another arrow function, it will not give us the result we need.

- Event handlers

Events in JavaScript are various operations that take place under specific conditions like the page loaded, the user clicking a specific button, the user scrolled, and so on.

When we work with events, we use a callback function, a function that follows the operation (click, load, scroll).

During the this keyword usage, we need to be sure that its reference doesn’t go outside the context.

We need to be sure that this refers to the scope it is surrounded by.

That’s why using an arrow function isn’t the best idea as this keyword will refer to the global object instead.

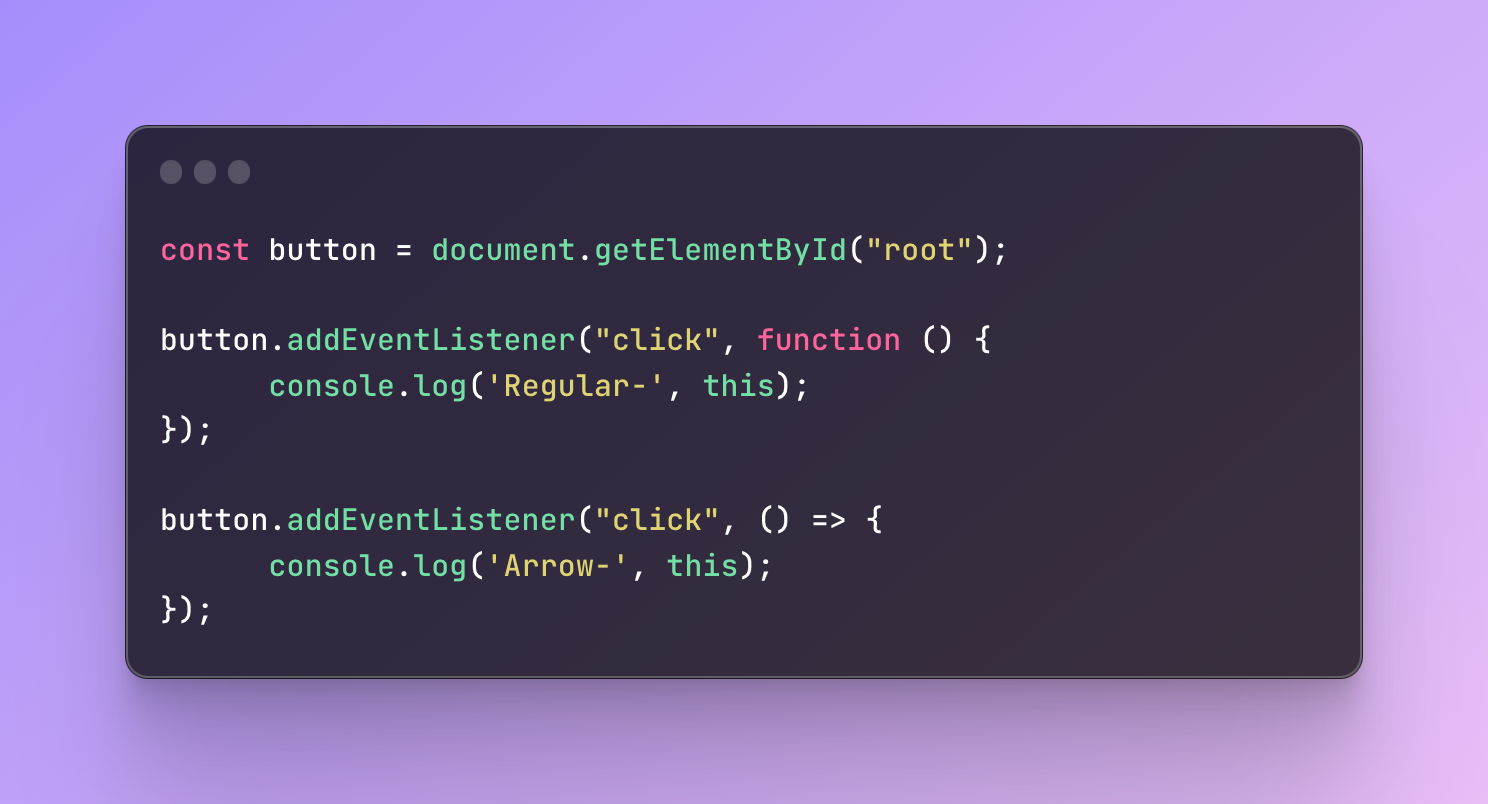

In this example, we are targeting a button with the id root.

The first event is implemented using a regular function and the second one an arrow function.

What will be the output?

The first click will show the button as this keyword refers to the button.

In the second case, it will return an object Window because it went outside the scope.

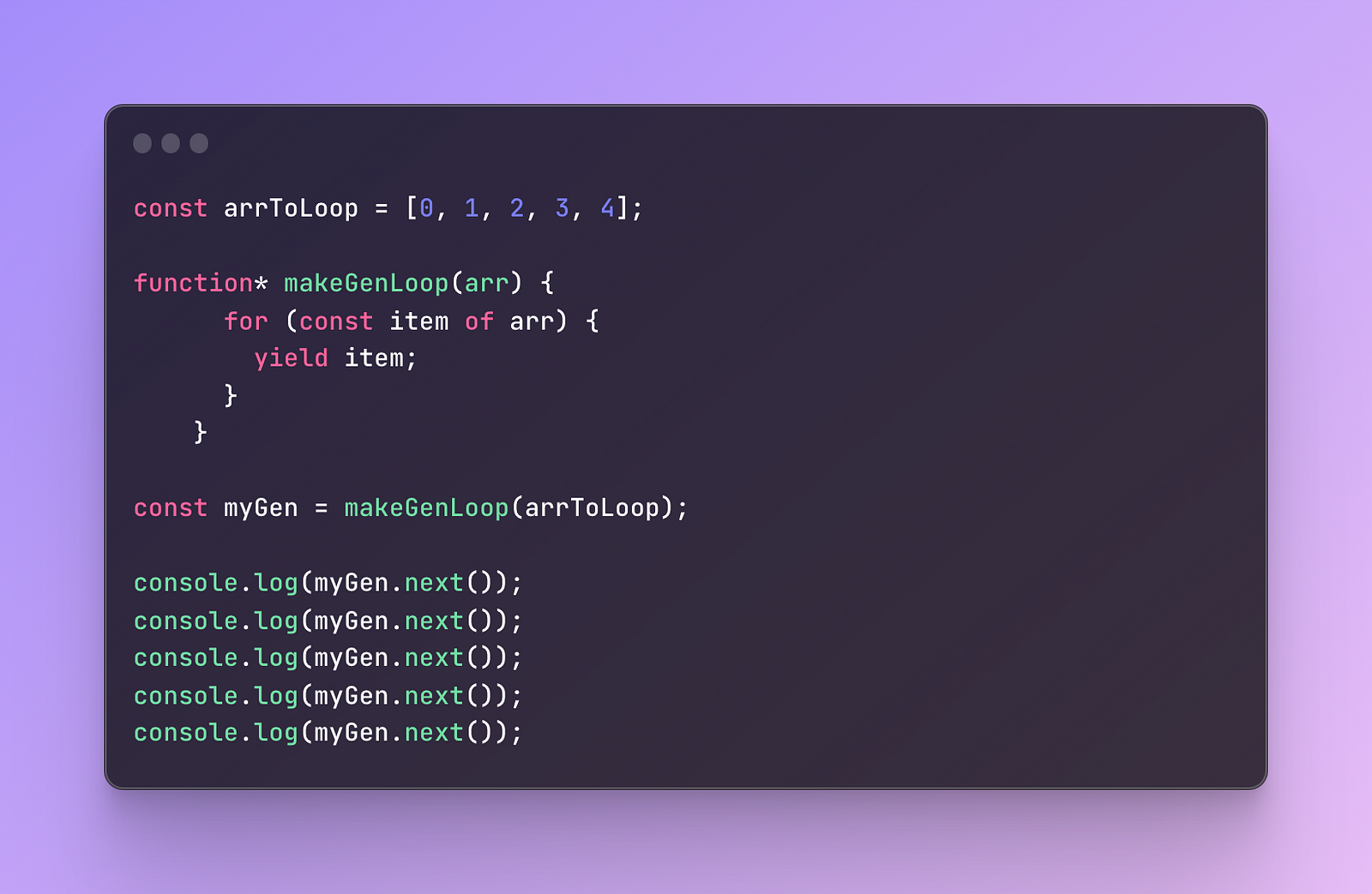

Generator function

A generator function is a special function that allows you to control the execution process — you can pause and resume it while generating values one by one!

To create a generator function you need to add an asterisk(*) after the function keyword and inside the body you use a keyword yield which pauses the execution process to return the “yielded” value.

Next, the function can be resumed to yield the next value.

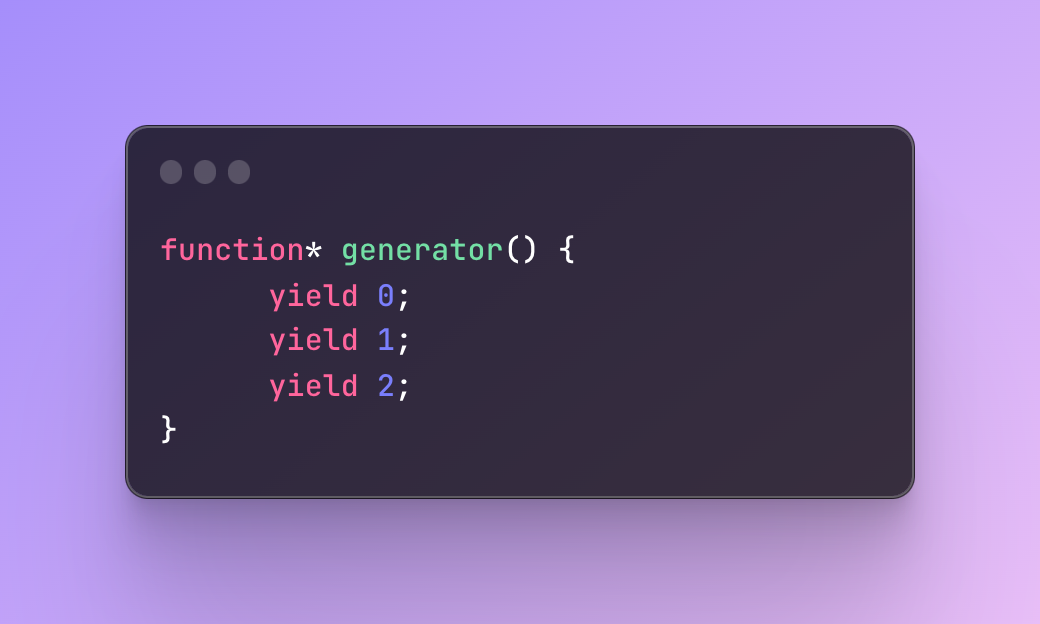

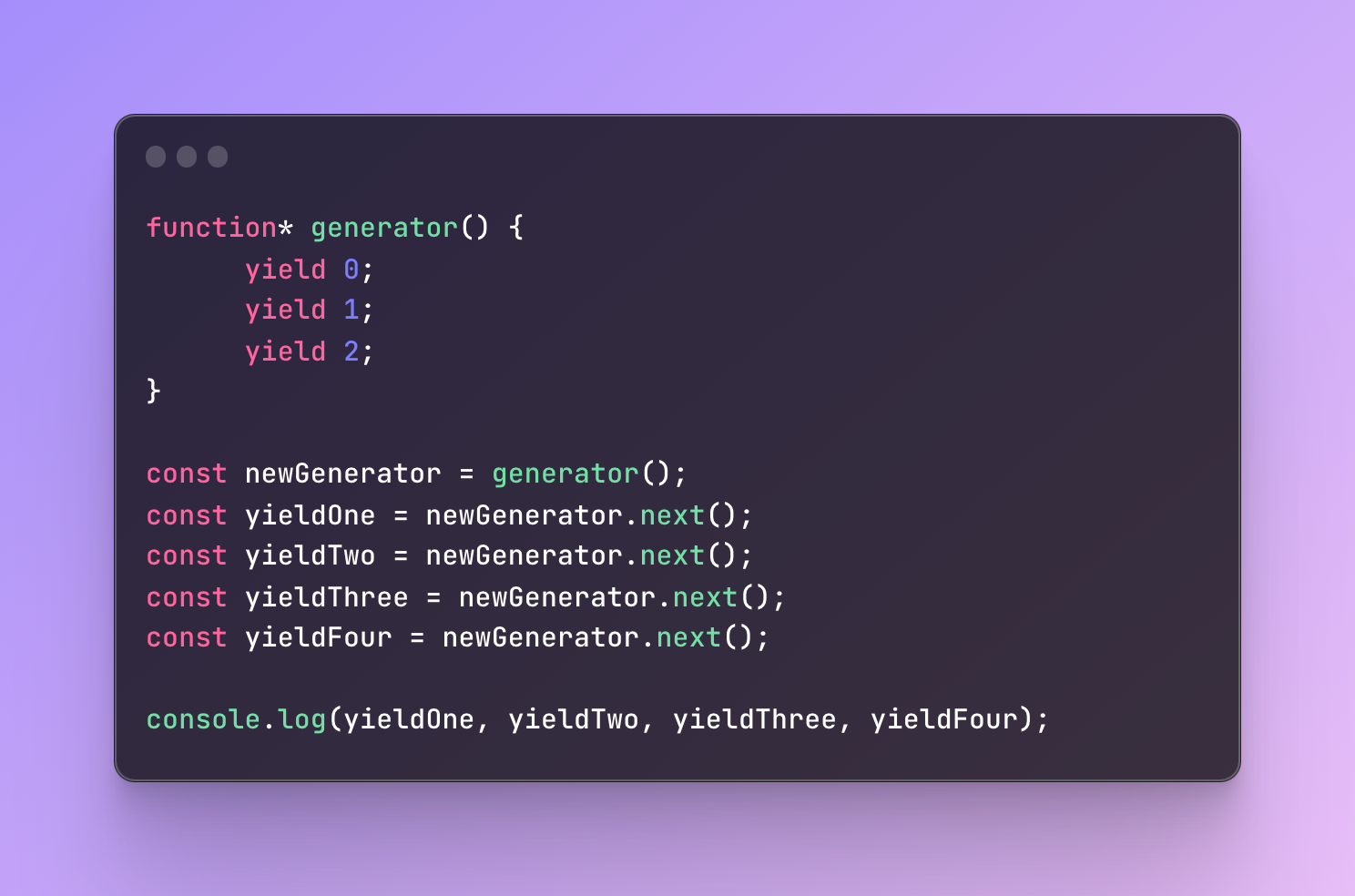

The syntax is a little different but overall very similar:

This doesn’t make sense much but let’s go further.

When you call the generator function it doesn’t execute right away like a regular function.

Instead, it creates an iterator object aka a generator object which is going to control the execution of our generator function.

Iterator is kind of a tool or feature in JavaScript that enables us to go through each value, one at a time, across various collections of data.

Iterator object has various methods that help us to control the execution process of the function.

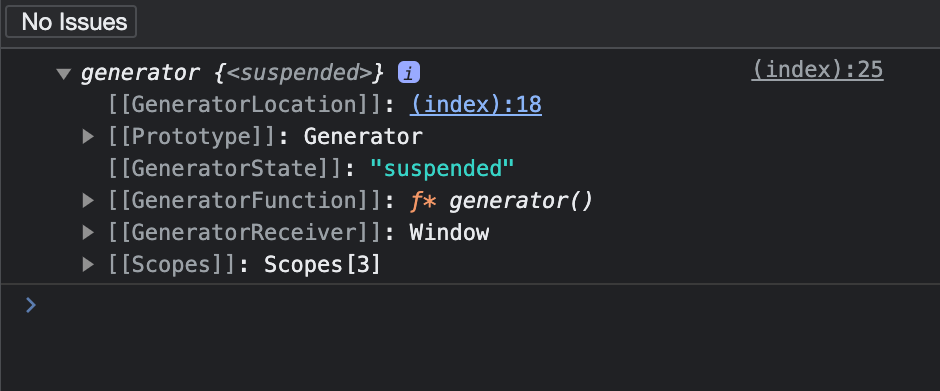

Let’s save the generator function and inspect what it creates:

Once we check the console, this is what we get:

When we call the function it simply creates this generator object but we need to use methods to make the function do something.

So it doesn’t execute the function, it’s a tool to execute the function in the future.

Generators can have several statuses:

Suspended: A generator is created but hasn’t executed anything yet, it’s paused.

Closed: The generator got terminated. There can be several reasons: we finished yielding all the results, we used a return or we threw an exception. Keep reading further to understand better what all this means.

Generator methods

Generator methods are actions that help us to execute the function and yield a result from it.

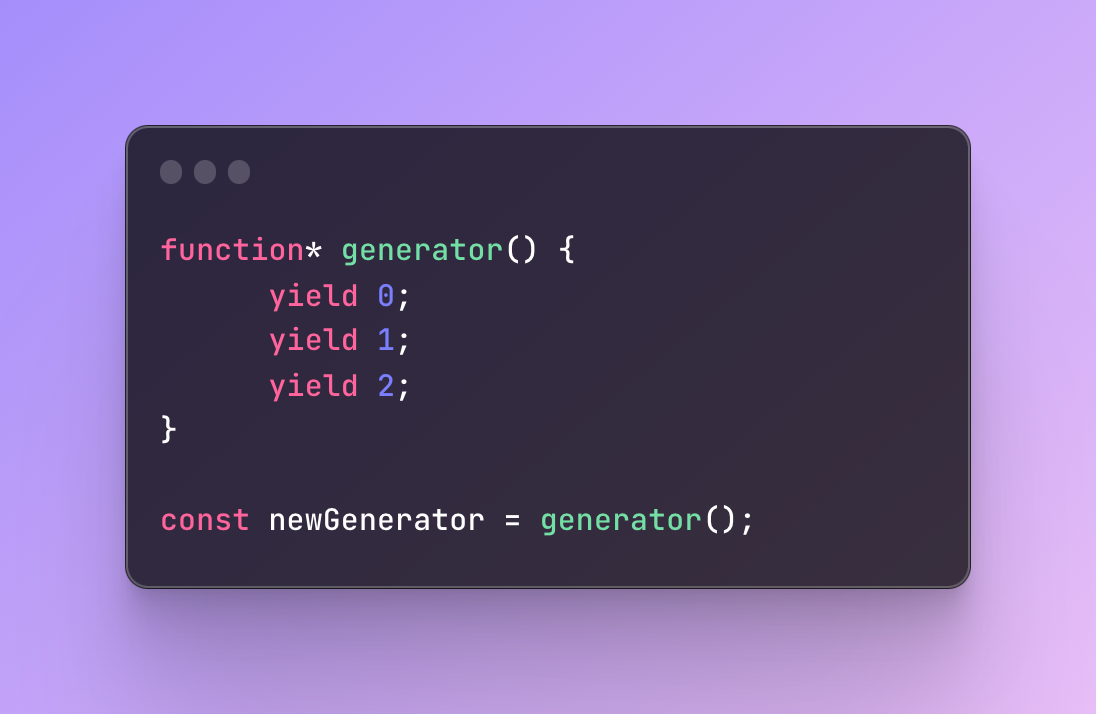

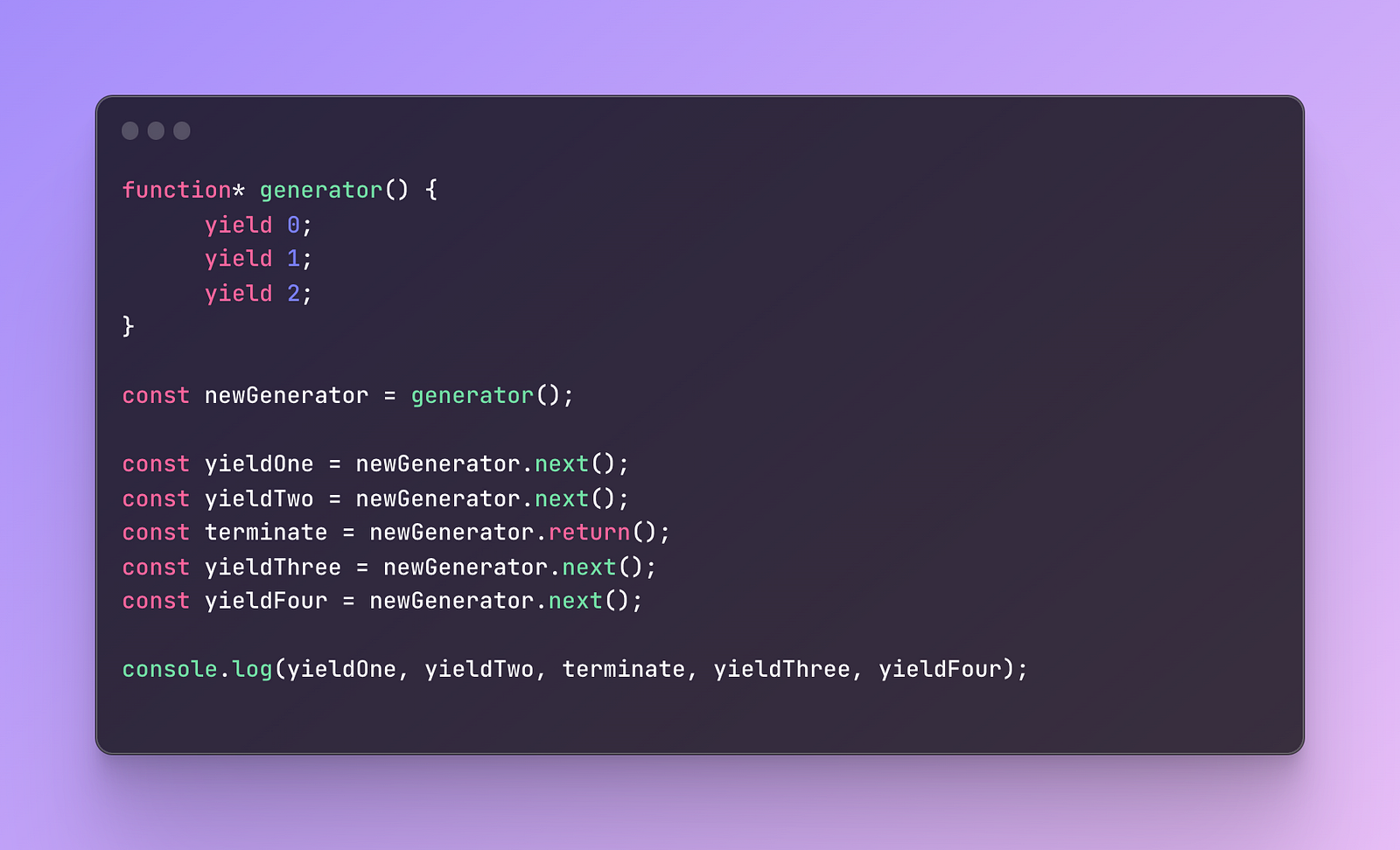

First, let's save our generator in a variable:

Next, let’s start yielding results using one of the methods called next().

This method will yield the first yield only, not all of them.

After we yield the first result, the execution will pause.

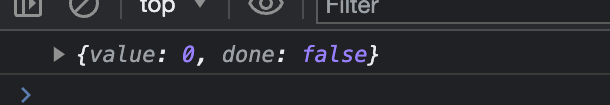

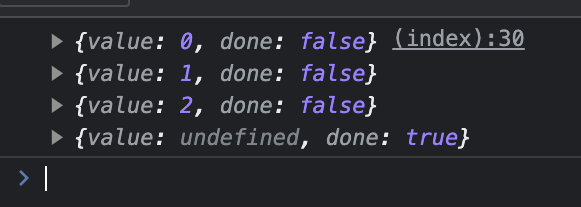

As a result, we will receive not just 0 but an object with two key-value pairs:

#1 The value property is the result we need to receive. In case there is nothing to yield and we try to use the next method anyway, it will return undefined.

#2 The done property is a boolean that indicates whether the function finished execution and if there are more results to yield. If the done property is false, this means we have more to yield, otherwise, it’s true.

The next method

Instead of logging it to the console let’s save every yield and show them all:

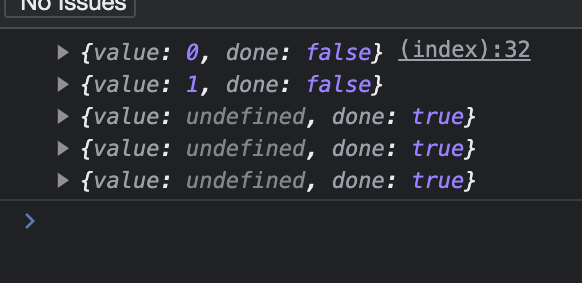

As a result, we will see the following:

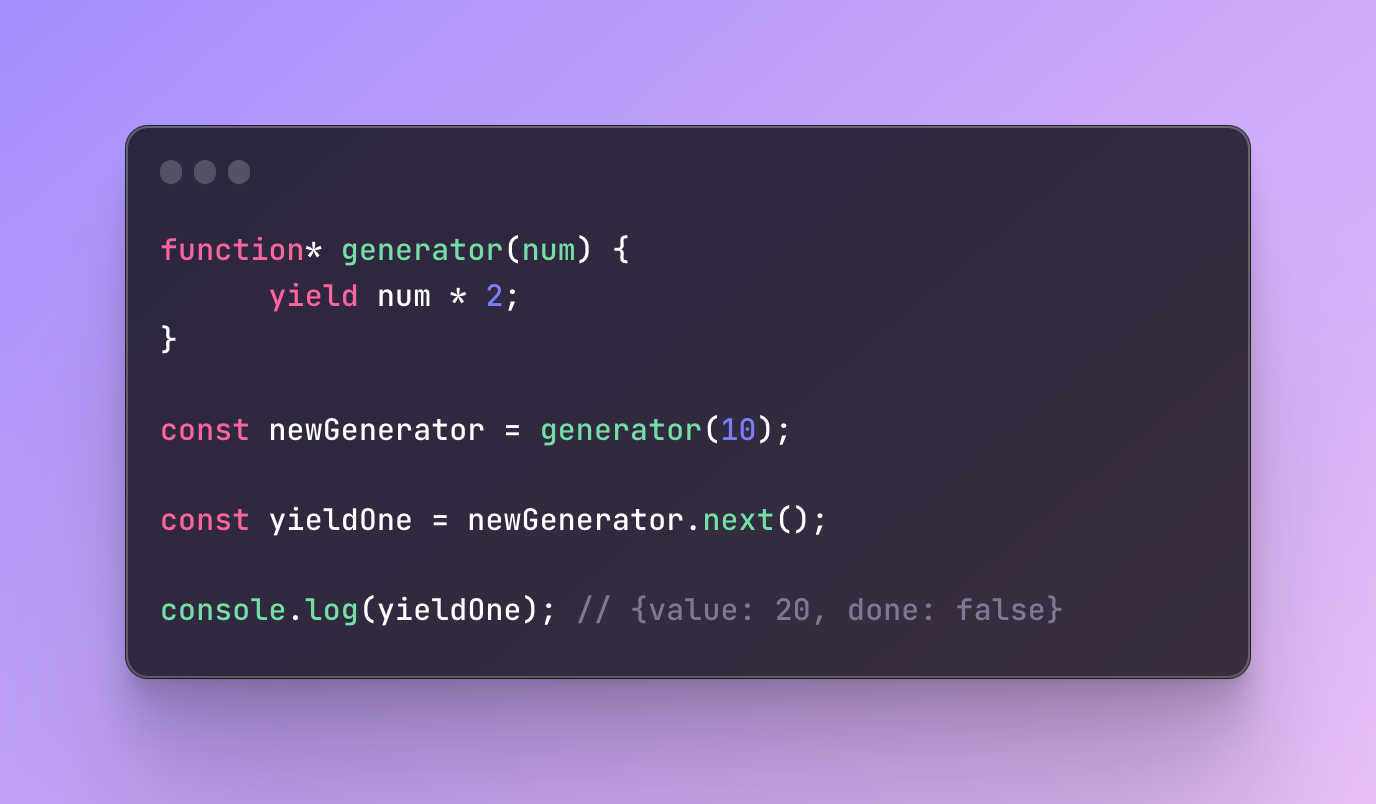

Similar to regular functions, we can pass arguments and return some calculated values. You don’t always need to return just one static value like in previous examples.

In this example, we passed a number and as a result, returned the double amount. You can pass as many arguments as you like.

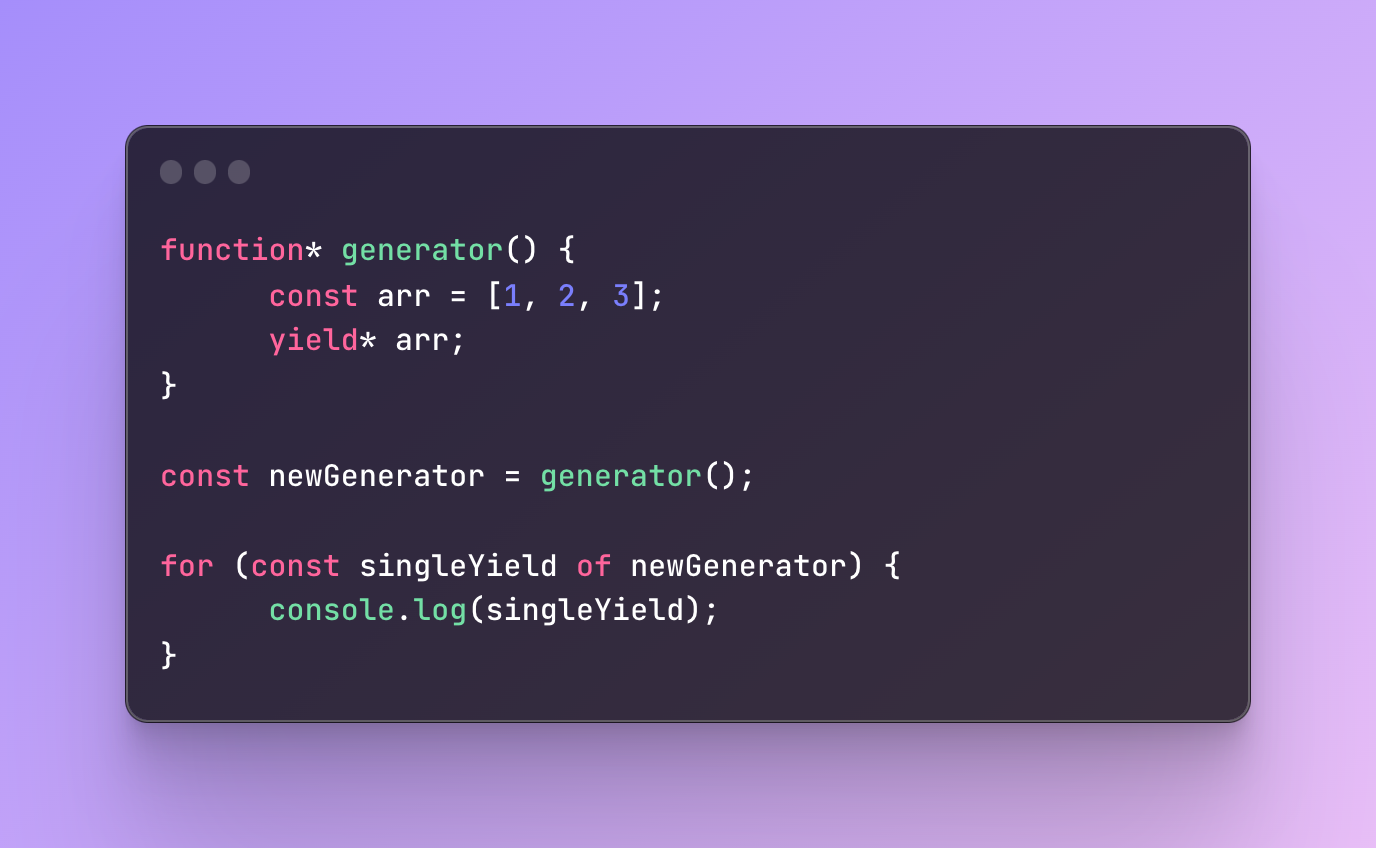

Yield or Yield*

You can also use yield in different ways. When we use simply yield, it stops execution and returns one value that was written after this keyword.

When we add an asterisk(*) at the end of the yield, it will iterate over the data we wrote after it and return each value until it’s done. Usually, we add data that can be iterated through.

As a result, you will see 1, 2, and then 3.

Another way you can use yield* is to delegate the yield of other generators. This way you can combine several different generators that bring one result or just make a structure more organized:

As a result, we will receive “hello” and then “there”.

The return method

The next method that you can use is a return which terminates the execution and if you try to use the next method again, it will always return an undefined value. The done property will be set to true.

Let’s add a bit more code to our previous generator:

I added a new variable where I used a return method. As a result, you will see the following:

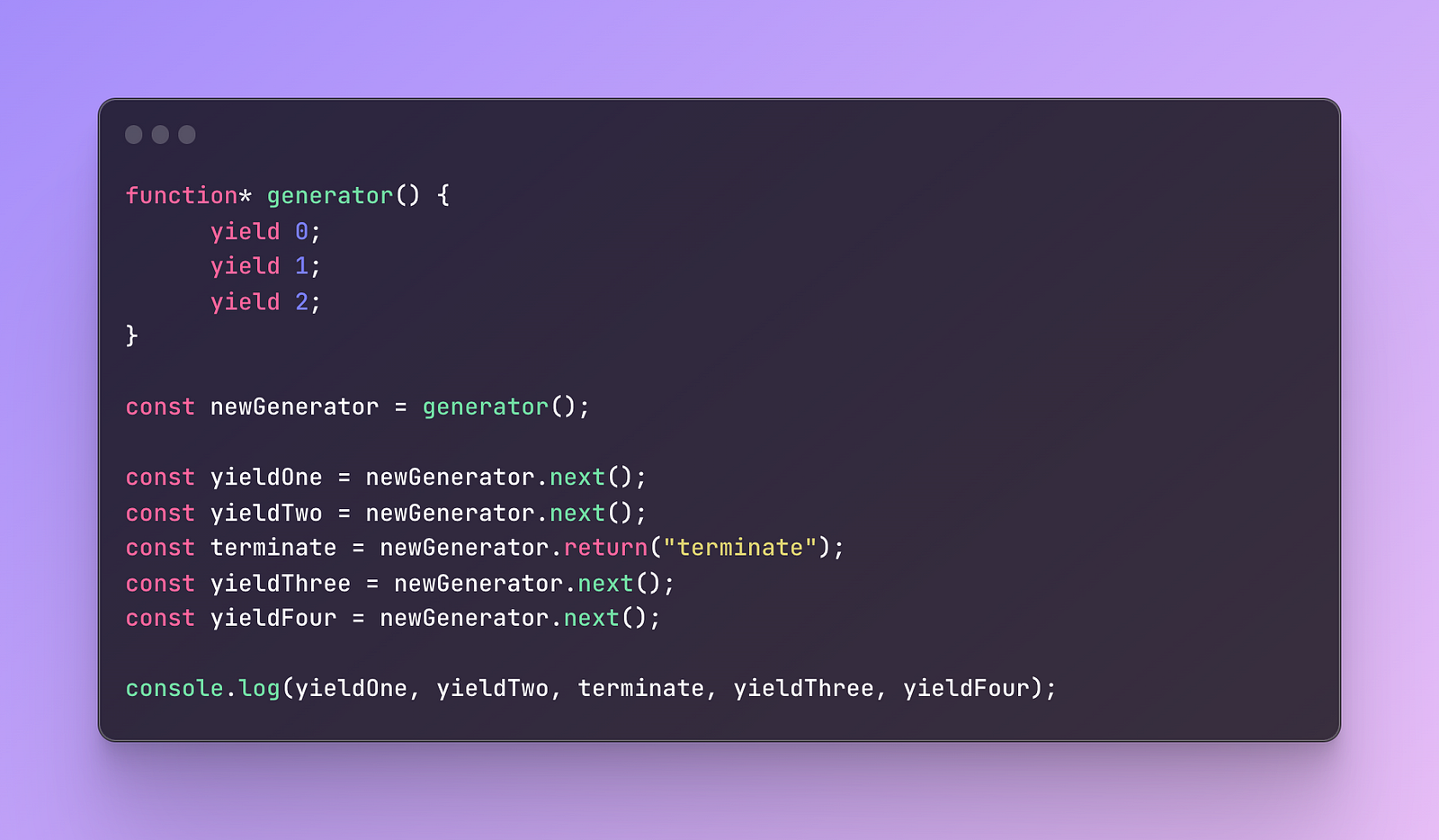

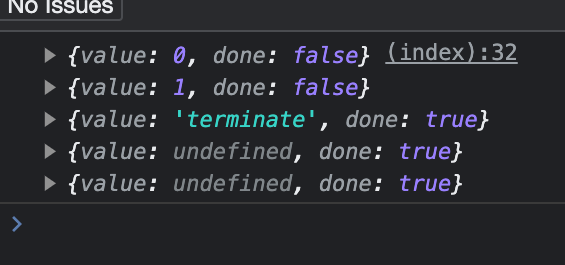

Additionally, we can pass a value to the return method and instead of returning the value of undefined, we can pass the final value we want to be returned.

Let’s try it out:

What do you think will be the result?

As you see, when we returned the final value, it is now replaced with terminate however the next ones remain undefined.

The throw method

The throw method is used to terminate the execution and throw an exception.

An exception is an event that is unexpected, most often it’s an error that we didn’t expect.

To handle such errors we need to use try…catch block. This block is a statement in JavaScript where in the try block we place the code we suspect might throw an exception and in the catch block we handle the error.

There are also other blocks we can use, for example, finally. In this block, we do something that will execute no matter if there is an error or not.

As a result, it’s a great idea to use the throw method along with try..catch because we can handle the flow of the situation and handle the errors.

Let’s implement the throw method:

In this example, we yield the first result after which we throw an exception.

By using a new Error we create an error object and add a custom message.

Next, we try to yield the result again.

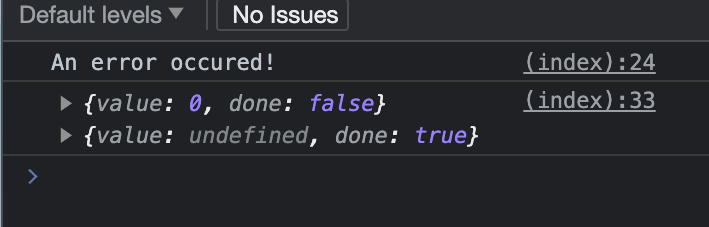

What will happen?

We indeed successfully yield the first result and then we throw an error. Due to this error, the execution is terminated and the second yield is undefined.

Why?

Because the execution has stopped and the rest cannot be revived anymore.

Pros and cons of generator functions

Pros

“Lazy” execution: This means that these functions are executed only when you call the next method. This can be useful when you don’t need all values.

State: Their state remains the same while you keep calling your next value and this eases the process of creating your own iterators. This way it’s easier to control the flow.

Dealing with infinity: Considering that you are controlling when to get the value and when to stop, this makes it easier to work with infinite sequences like natural numbers, Fibonacci sequences, or randomly generated numbers, for instance.

Memory-efficient: Instead of retrieving tons of data, you save a lot of memory by yielding only the part of values instead of storing the whole collection of data.

Cons

Hard to reach: You cannot perform several iterations in parallel which we might need sometimes. You also cannot retrieve just any random element and we cannot start at any part of the code.

Complex: Though it seems like we have a lot of control, at the same time it adds an extra layer of complexity. We have to expand our logic with a lot of code and extra yield, yield, yield.

No usage in callbacks: In callbacks, we are able to use generators however it’s not the best idea. The main idea of generators is to make asynchronous code look like it’s synchronous. When asynchronous functions are harder to control, generators may be handy at times. Incorrect usage might lead to callback hell and more complexity. Instead, better to use modern async/await.

Usage of generator functions

I think even after considering the pros and cons of generators, it can be hard to understand if we even need them.

I noticed that not much is written about them and as if they are useless. There seem to be a lot of modern solutions.

Let’s take several use cases and try to understand if we really need generators.

Loops that we can pause and resume

One of the reasons I found about the usage of generates is the ability to control loops much better, especially when it’s complex loops or asynchronous.

One of the reasons is said to be the internal state management. This means that when you pause the loops with yield, you can continue the loops exactly where you left off.

Does it mean only generators can do it? Absolutely not.

There are a lot of other ways to achieve this.

The async/await with a custom iterator

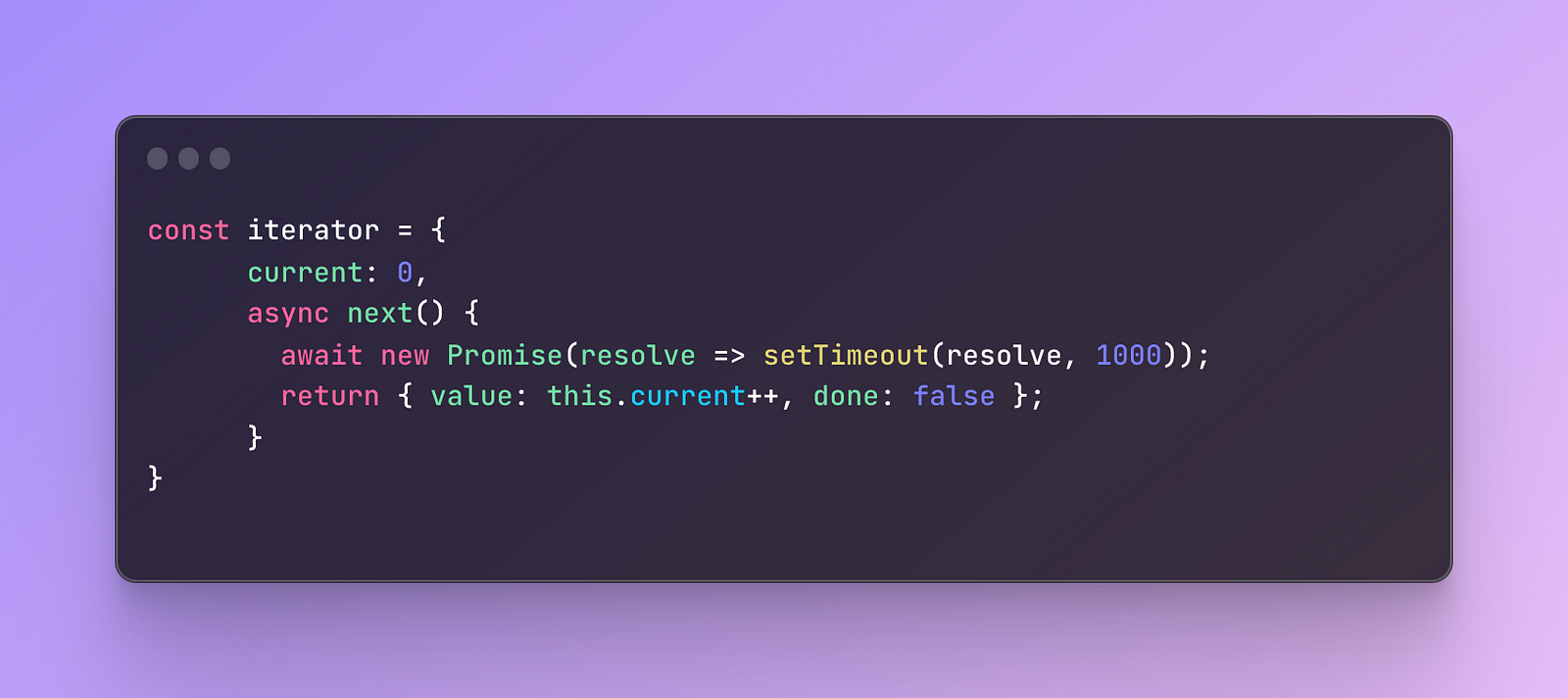

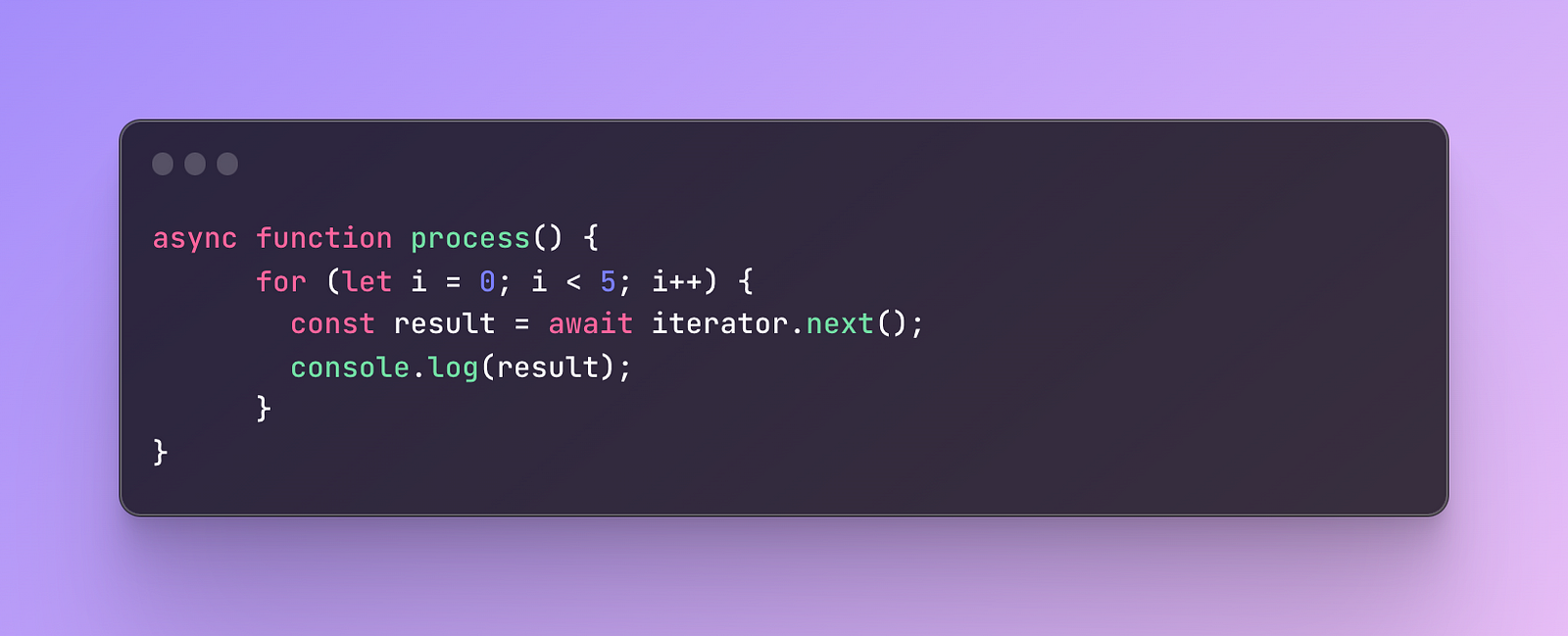

First, let’s define a custom iterator object that acts as if it’s asynchronous.

Then inside it, we will create a property current that defines the current state.

Next, we will add a method called next that awaits 1 second before proceeding further. This will simulate the asynchronous operation and artificially delay responses.

Finally, we will return an object similar to the generator response.

Time to implement the next method.

We will create an asynchronous function that interacts with our iterator and returns the result object.

It will be asynchronous because we don’t want it to block the other asynchronous operation that we made artificially in the iterator.

We will also use await to pause the operation and wait for our Promise to be resolved.

We also add a for loop that will run five times, this way we say that we want to call the imaginary next() method 5 times.

Next, for everything to work, we simply need to call the function:

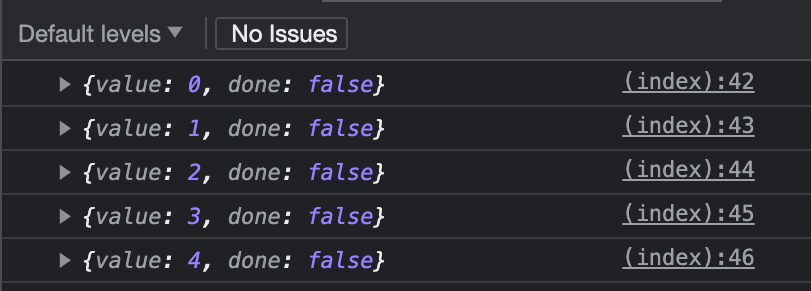

As expected, we received a similar result and we can control how to run the loop:

Let’s compare this to the generator function and re-create everything above to a generator:

In this example, we created an array, similar to our for loop. Then we added a generator function where we loop through an array and yield each item.

Here are the results:

Exactly the same as it was in the previous case.

Visually, in means of the amount of code, I personally think that it’s almost the same, you can count the characters if you will.

Also, the generator function seems less complex and as if it’s easier to understand it.

The main question I had about generators is in what real-life case can I use them?

I found several answers what real-life examples of generators:

- Processing big data or working with big data, one at a time, when you don’t want to affect the memory.

One of the examples is working with APIs when you implement pagination.

Instead of fetching the whole data, you can fetch only part of it and show this partial data depending on which page you are on.

Working large databases, working with data formats like JSON, where you can pass or receive data row by row, and working with an image editor for instance, where you do batch updates like applying a filter.

- Streaming data is data that you keep receiving endlessly, let's say the same real-time analytics, currency exchange rates or stock market data, real-time social media feeds, and so on.

Generators in such situations should process and analyze everything step by step to avoid overload.

- Task scheduling is another reason why generators might be useful. Situations when you need to manage and control several tasks that need to be done in sequence. Some examples are backup and restoration processes, building pipelines where you need to control several steps, database, migration processes, and so on.

Can you replace generations for such functionalities?

Yes.

You can use async/await and promises just like we did before.

You can use additional queries for API calls to retrieve filtered or partial data. If there are no queries supported you can also retrieve the data and cache it for later use.

If it comes to streaming data there are a lot of alternatives like Node.js streams, Websocket API, and message queues like Apache Kafka, there are also many streaming libraries.

For task scheduling, we also have many alternatives like task queues and various schedulers.

In the end, it’s really hard to prove that without generators you can’t do anything. That’s why I decided not to dig too deep for now.

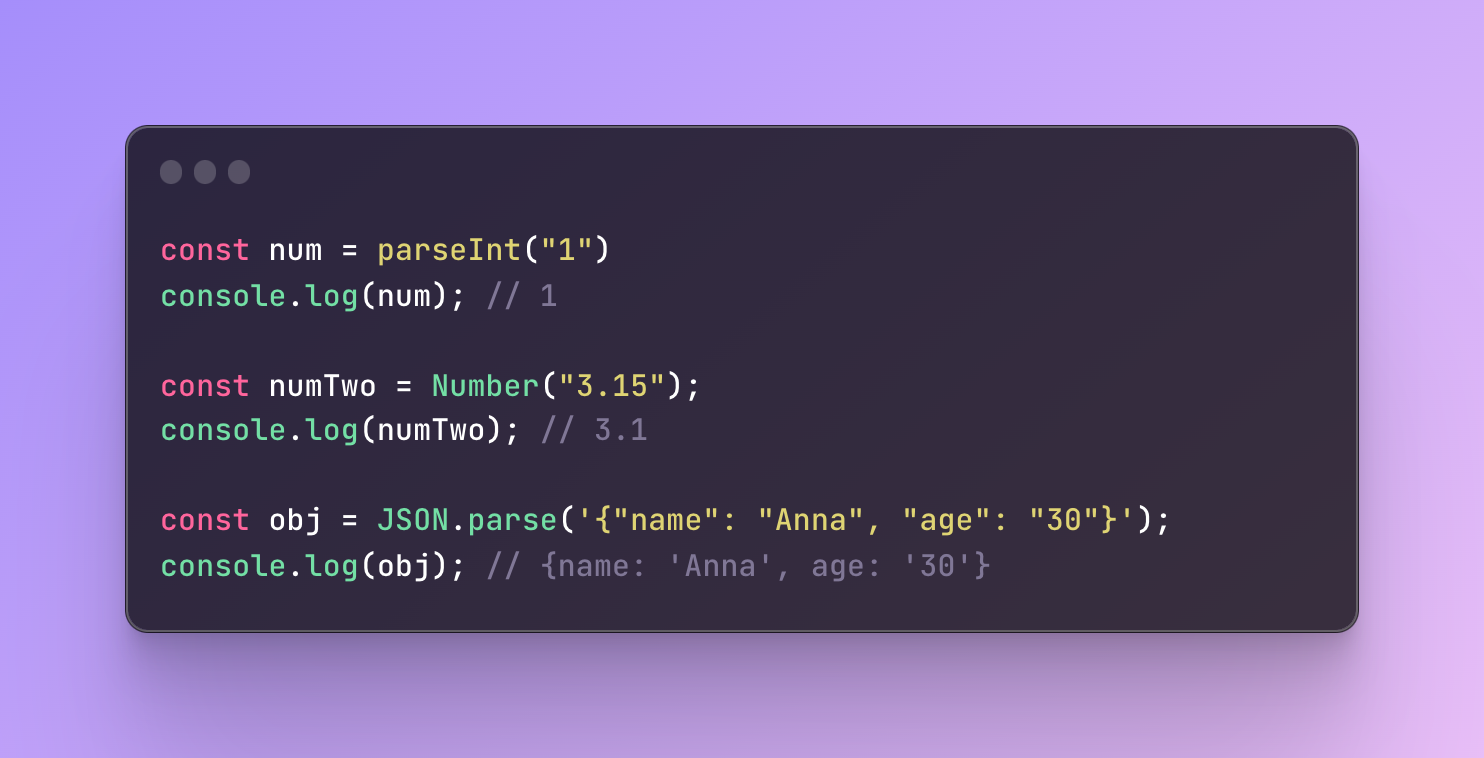

Unary functions

In JavaScript, an unary function is a function that takes only one argument and transforms its value.

Though this is a very simple example, there are many various situations where we can use unary functions.

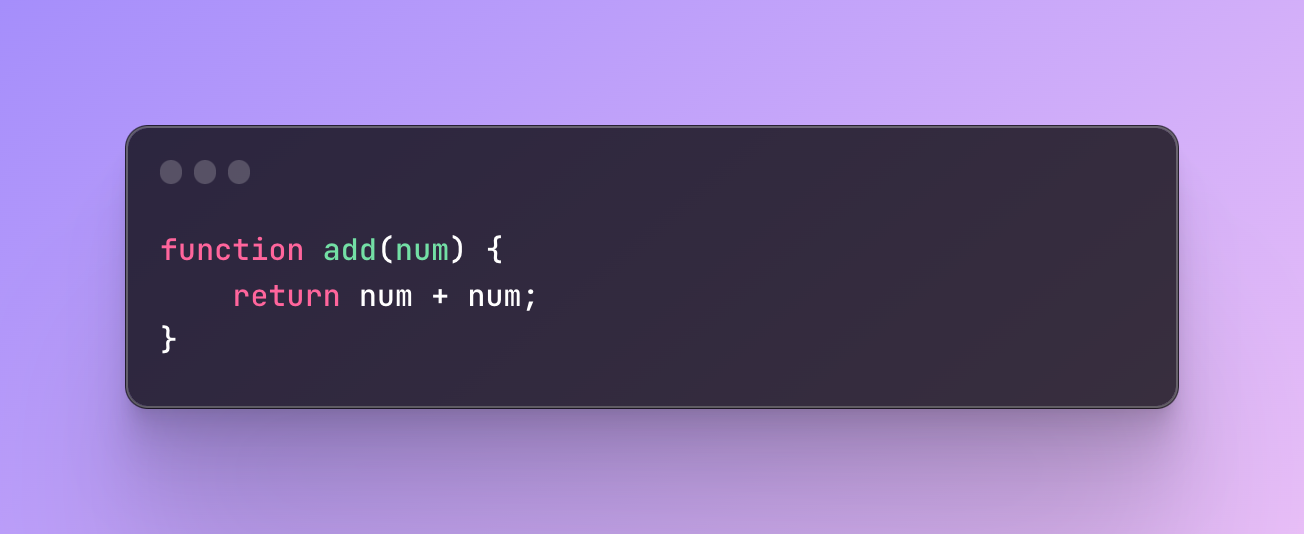

Built-in methods

One of the examples where we often have unary functions is built-in methods. There are methods that accept one value and perform some operation on this value.

These are several examples of unary functions that receive just one argument — converting string to an integer, converting string to a floating-point number, or parsing JSON and converting it to an object.

Besides the functions, we have a lot of unary operators that are very similar to functions.

The main difference between functions and operators in this scenario is the fact that operators existed in JavaScript earlier than functions as its design consisted of operators inspired by C-style languages. Operators in such programming languages are symbols or keywords that perform operations, just like functions do.

That is why we have many unary operators in JavaScript right now.

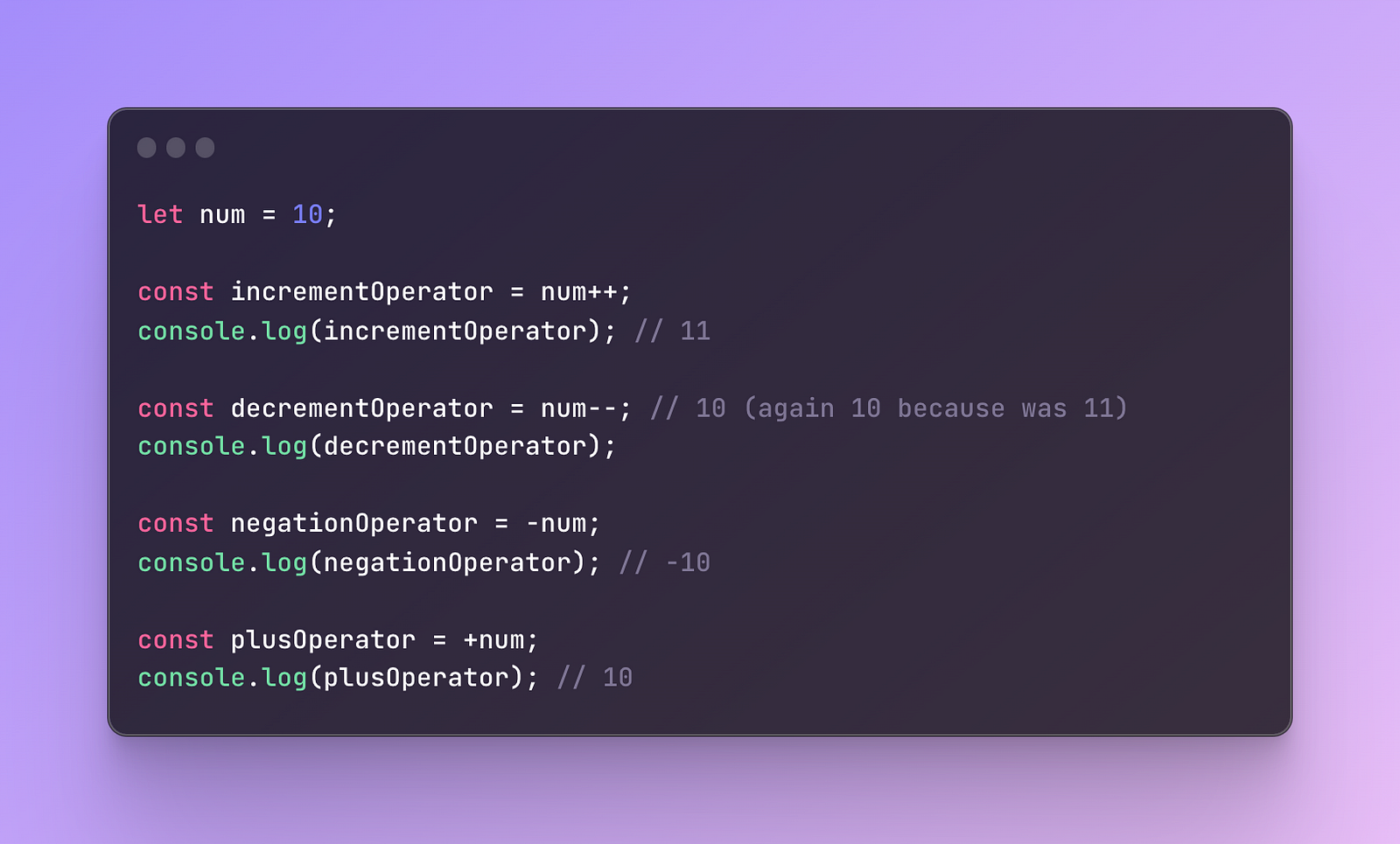

Let’s cover some examples of unary operators:

These are a few examples for a basic understanding.

The increment operator increments the number by one, then decrements by one, negation can convert a number to a negative value, and the plus operator is often used to convert a value to a numeric value.

When are unary functions useful?

Unary functions can be useful in two situations:

Currying

Higher-order functions

As we already covered higher-order functions, are the functions that receive functions as an argument and/or return other functions.

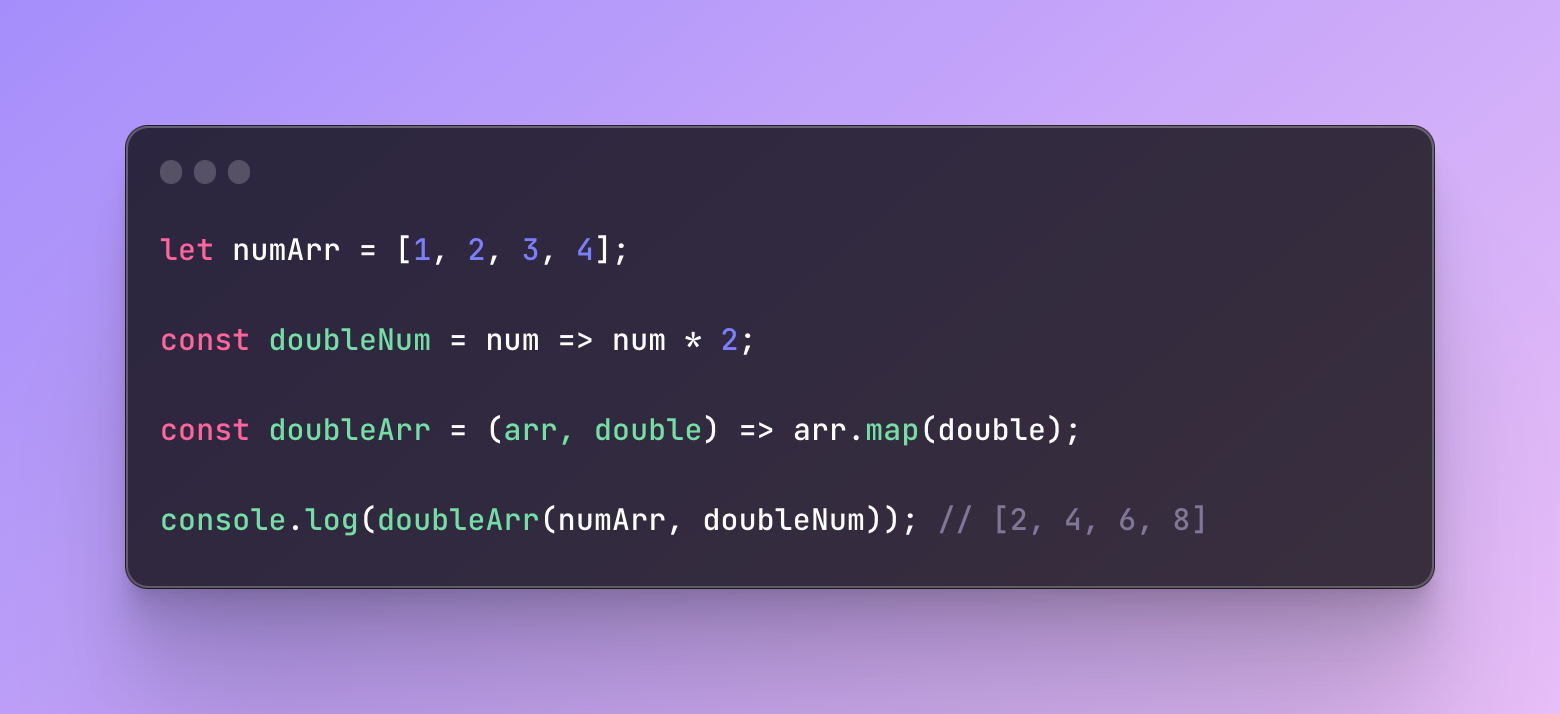

This is also a good example of where we can use currying:

As you can see, we used a high-order function that receives an array and another unary function that doubles each item in an array.

Currying functions

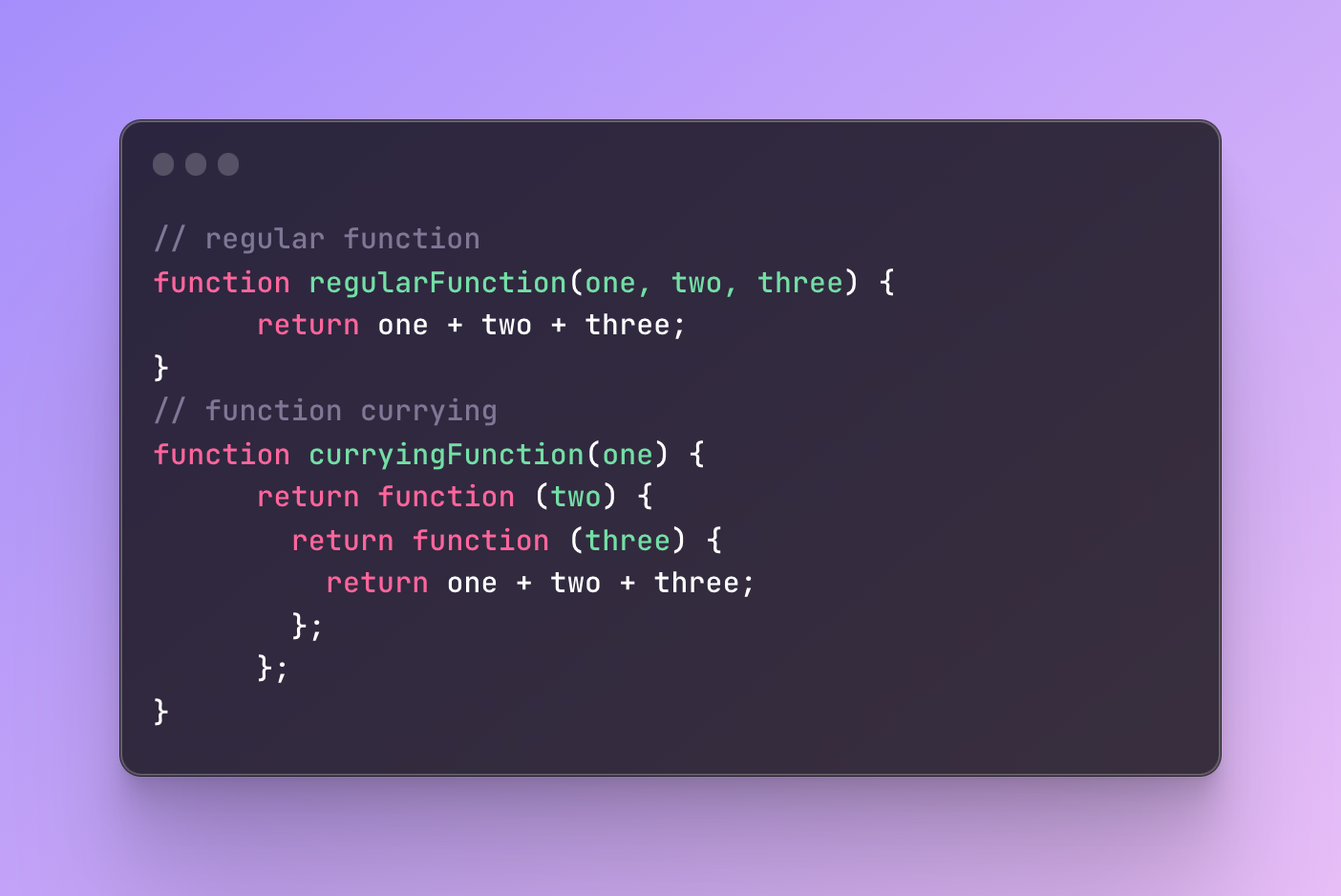

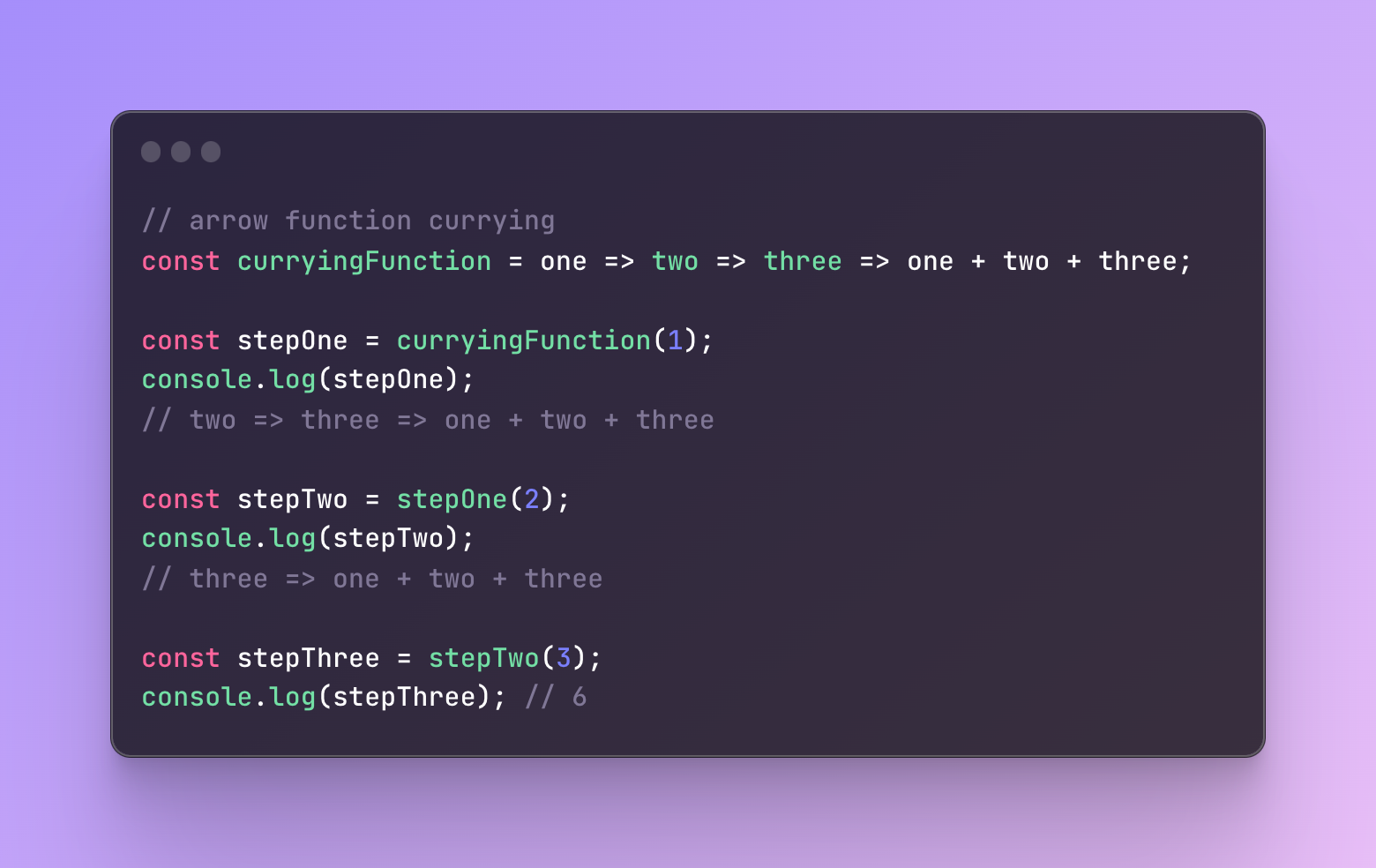

The reason we discussed unary functions is that they are often used in a functional programming technique called currying.

Currying is a series of unary functions, specifically a chain of functions where one function returns another function until the final result is received.

In other words, instead of passing several arguments to one function, you can divide it into several parts where each function receives only one argument.

The topmost function receives one argument and returns another function that expects another argument.

The next function expects and returns the same until the innermost function collects all of them and returns the final result.

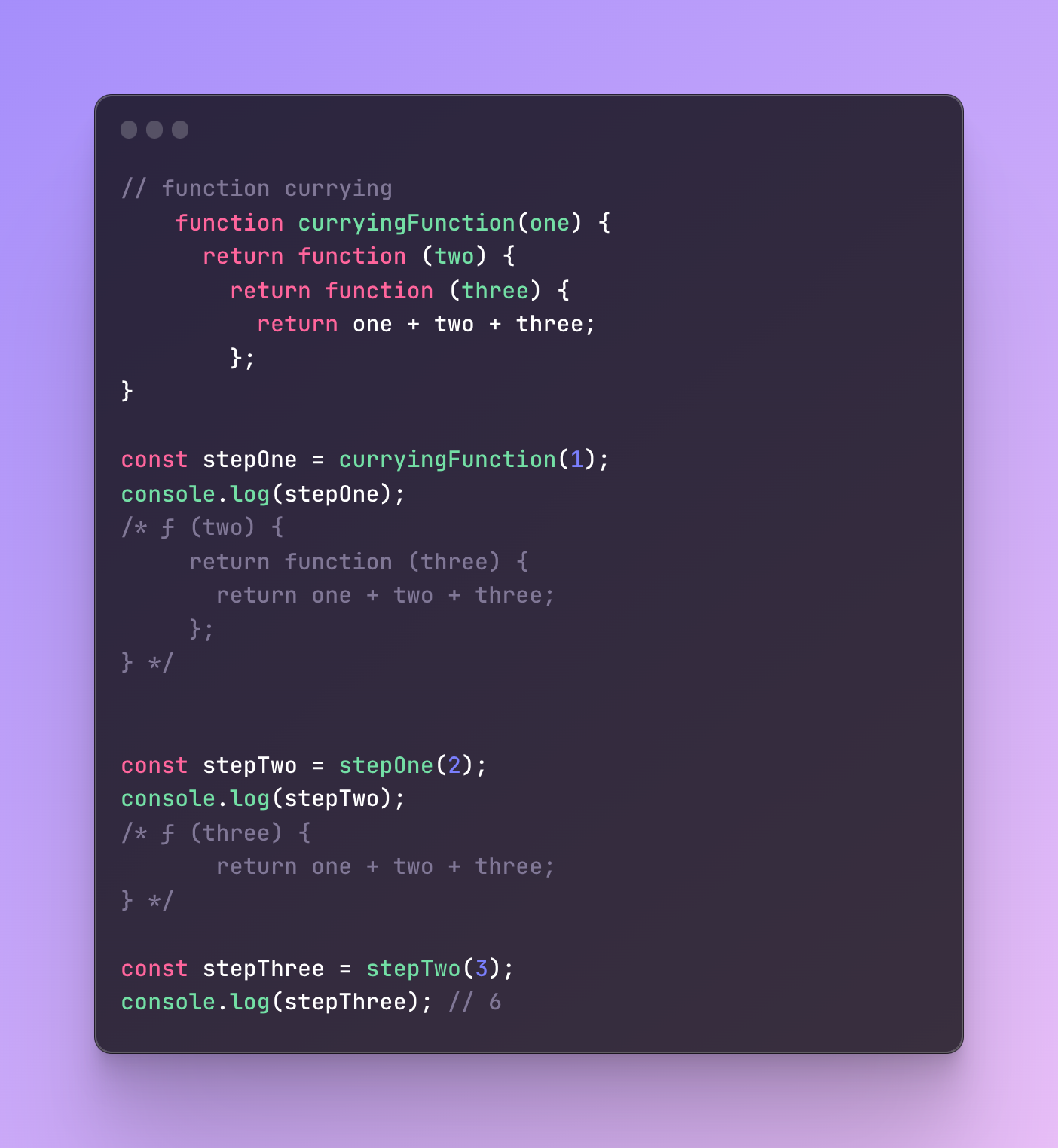

Let’s get the results:

As you see, the first step is the upper-most function, then I passed another argument to the second function, and finally one more time I received the final result.

The amount of arguments a function takes is often called arity.

If a function takes 2 arguments it’s a two-arity function, if 3 then three-arity, and so on.

We can also convert the same function currying to an arrow function:

Everything remains the same, we simply used less code, and looks much cleaner now.

When to use function currying?

One of the best places where we can use currying is a function composition.

A function composition is when you combine several functions to create a new function.

Function composition is the best place where we can use function currying.

Imagine, that you want to perform two various operations.

-In one case, you want to take the value, increment it by one, and then double it.

-In another operation, you want to take the value, square it, and then subtract two from it.

Instead of writing a lot of functions for each operation, we can compose several functions together!

#1 First, we can make a composition of increment and doubling.

#2 Then, we can compose squaring and subtraction of two.

If you notice, we also have similarities between these two options.

They both are going to take one value and both perform two actions.

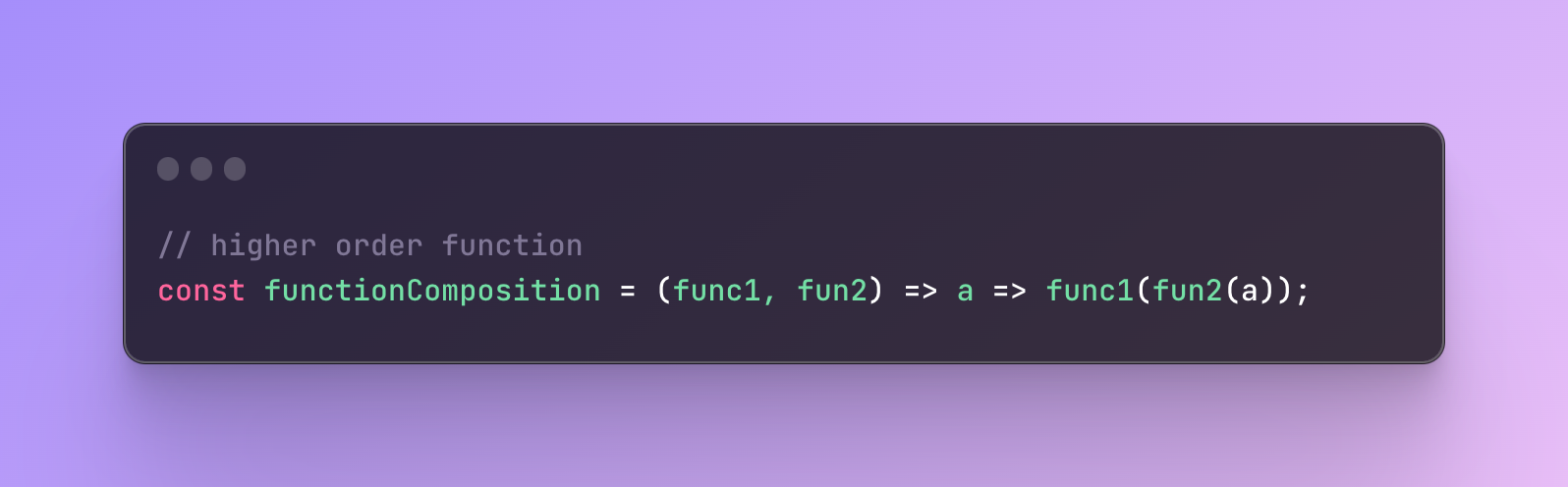

As a result, instead of writing many functions, we can first write one function that will receive two functions and perform actions on the value it receives.

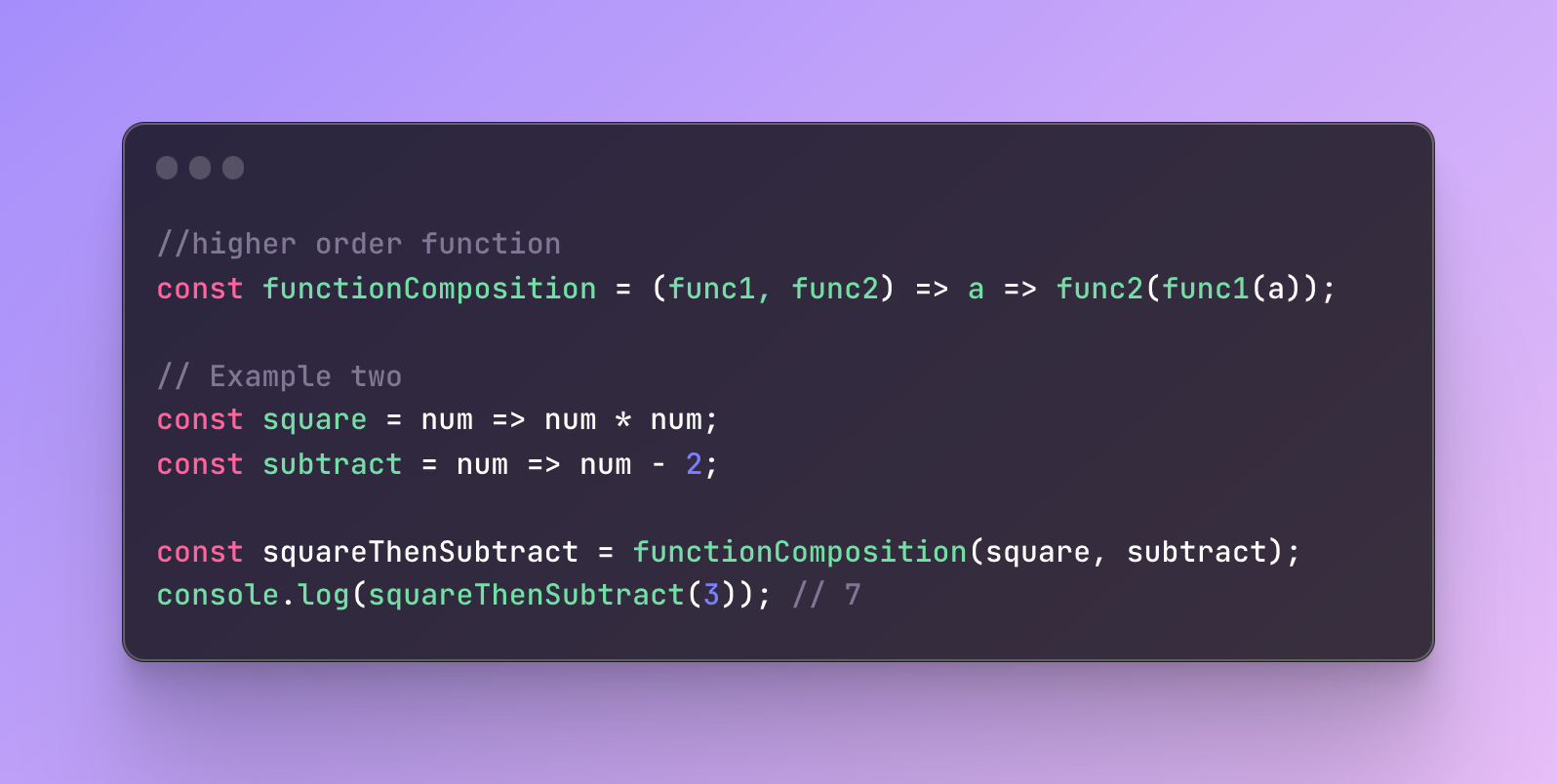

In our case, we need a function that receives two functions, right?

The function above is a reusable function that is going to receive two functions — func1 and func2.

The parameter “a” is the value our function is going to receive.

As a result, it will first perform an operation on a function one, func1 and the result of the func1 will be passed to the second function, func2.

So the function composition result will be the result of a second function argument which performs an operation on a result of the first function argument.

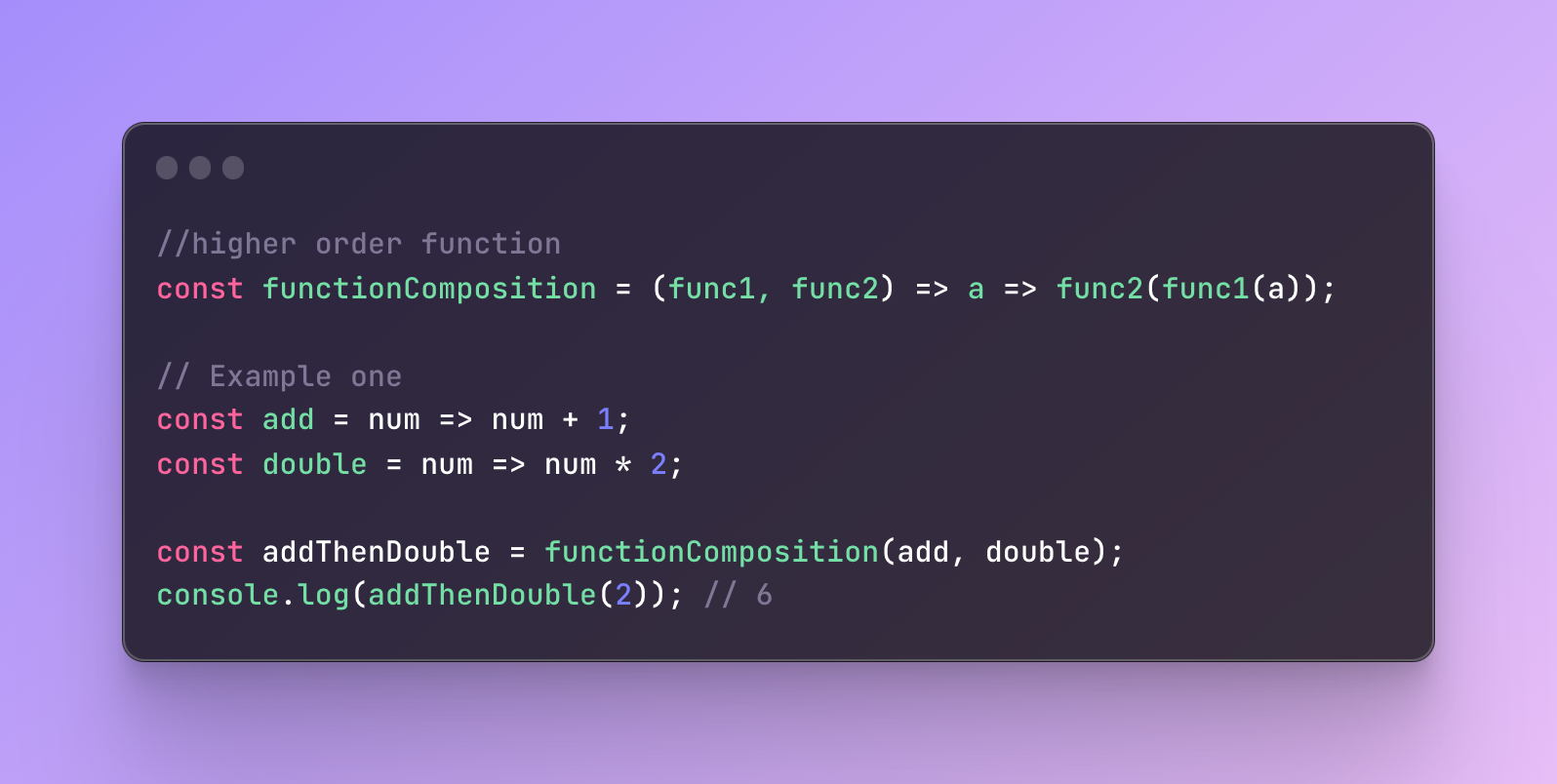

Let’s understand what is going on in the code above.

The function composition expects two functions.

We are going to achieve the first goal — increment the value by one and then double it, so we need two functions. These two functions we need are add and double.

Next, we need to pass these functions to our function composition.

But as you see we didn’t pass any arguments yet. Let’s check the value of the addThenDouble:

The value is a function reference, it doesn’t do any calculations just yet.

The value we save right now is only the function reference. We need to call this function.

That’s why in the console we call the function addThenDouble and pass a value we want to work with.

As a result, we will receive 6.